14.3 Evaluating Psychotherapies

Many Americans have great confidence in psychotherapy’s effectiveness. “Seek counseling” or “Ask your mate to find a therapist,” advice columnists often advise. Before 1950, psychiatrists were the primary providers of mental health care. Today, many others have joined their ranks. Clinical and counseling psychologists offer psychotherapy, and so do clinical social workers; pastoral, marital, abuse, and school counselors; and psychiatric nurses.

Psychotherapy takes an enormous amount of time, money, and effort. A critical thinker might wonder: Is the faith that millions of people worldwide place in psychotherapy justified? The question, though simply put, is not simply answered.

Is Psychotherapy Effective?

LOQ 14-

Imagine that a loved one, knowing that you’re studying psychology, has asked for your help. She’s been feeling depressed, and she’s thinking about making an appointment with a therapist. She wonders: Does psychotherapy really work? You’ve promised to gather some answers. Where will you start? Who decides whether psychotherapy is effective? Clients? Therapists? Friends and family members?

Clients’ Perceptions

If clients’ glowing comments were the only measuring stick, your job would be easy. Most clients believe that psychotherapy is effective. Consider 2900 Consumer Reports readers who rated their experiences with mental health professionals (1995; Kotkin et al., 1996; Seligman, 1995). How many were at least “fairly well satisfied”? Almost 90 percent (as was Kay Redfield Jamison, as we saw at this chapter’s beginning). Among those who recalled feeling fair or very poor when beginning therapy, 9 in 10 now were feeling very good, good, or at least so-

But clients’ self-

People often enter therapy in crisis. Life ebbs and flows. When the crisis passes, people may assume their improvement was a therapy result.

Clients believe treatment will be effective. The placebo effect is the healing power of positive expectations.

Clients generally speak kindly of their therapists. Even if their problems remain, clients “work hard to find something positive to say. The therapist had been very understanding, the client had gained a new perspective, he learned to communicate better, his mind was eased, anything at all so as not to have to say treatment was a failure” (Zilbergeld, 1983, p. 117).

Clients want to believe the therapy was worth the effort. If you invested dozens of hours and lots of money in something, wouldn’t you be motivated to find something positive about it? Psychologists call this effort justification.

Clinicians’ Perceptions

If clinicians’ perceptions were proof of therapy’s effectiveness, we would have even more reason to celebrate. Case studies of successful treatment abound. Furthermore, therapists are like the rest of us. They treasure compliments from clients saying good-

Therapists are like the rest of us in another way. We all sometimes suffer from two obstacles to critical thinking (Lilienfeld et al., 2014). The first, confirmation bias, is the tendency to unconsciously seek evidence that confirms our beliefs and to ignore evidence that contradicts them. The second is the tendency to see illusory correlations—

Outcome Research

If clients’ and therapists’ most sincere ratings of their experiences can’t inform us about psychotherapy’s effectiveness, how can we know what to expect? What types of people and problems are helped, and by what type of psychotherapy?

In search of answers, psychologists have turned to controlled research. This is a well-

In the twentieth century, psychology faced a similar challenge. British psychologist Hans Eysenck (1952) launched a spirited debate when he summarized 24 studies of psychotherapy outcomes. He found that two-

Why, then, are we still debating psychotherapy’s effectiveness? Because Eysenck also found that untreated people, such as those on waiting lists for the same treatment, had similar rates of improvement. With or without psychotherapy, roughly two-

Eysenck’s findings sparked an uproar. Some critics pointed out errors in his analyses. Others noted that he based his ideas on only 24 studies. Now, more than a half-

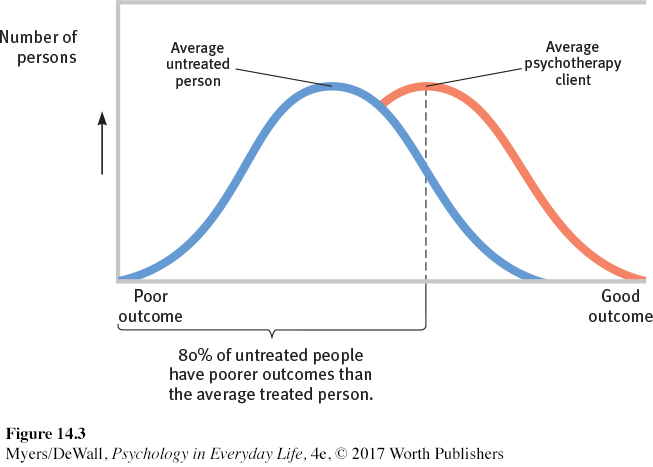

Therapists welcomed the result when the first statistical digest combined the results of 475 of these investigations (Smith et al., 1980). The outcome for the average therapy client was better than that for 80 percent of the untreated people (FIGURE 14.3).

Dozens of such summaries have echoed the results of the earlier outcome studies: Those not undergoing therapy often improve, but those undergoing therapy are more likely to improve, and to improve more quickly and with less risk of relapse. Moreover, between the treatment sessions for depression and anxiety, many people have sudden reductions in their symptoms. These “sudden gains” offer hope for long-

So psychotherapy is a good investment of time and money. Like prenatal care, psychotherapy reduces long-

It’s good to know that psychotherapy, in general at least, is somewhat effective. But distressed people—

Which Psychotherapies Work Best?

LOQ 14-

The early statistical summaries and surveys did not find that any one type of psychotherapy was generally better than others (Smith & Glass, 1977; Smith et al., 1980). Later studies have similarly found little connection between clients’ outcomes and their clinicians’ experience, training, supervision, and licensing (Bickman, 1999; Luborsky et al., 2002; Wampold, 2007). A Consumer Reports survey confirmed this result. Were clients treated by a psychiatrist, psychologist, or social worker? Were they seen in a group or individual context? Did the therapist have extensive or relatively limited training and experience? It didn’t matter. Clients seemed equally satisfied (Seligman, 1995).

So, was the dodo bird in Alice in Wonderland right: “Everyone has won and all must have prizes”? Not quite. One general finding emerges from the studies. The more specific the problem, the greater the hope (Singer, 1981; Westen & Morrison, 2001). Moreover, some forms of psychotherapy get prizes for particular problems. Behavioral conditioning therapies work well for specific behavior problems, such as bed-

But no prizes would go to certain other psychotherapies (Arkowitz & Lilienfeld, 2006). We would all be wise to avoid approaches that have little or no scientific support, such as

energy therapies, which seek to manipulate people’s invisible energy fields.

recovered-

memory therapies, which aim to unearth “repressed memories” of early childhood abuse (Chapter 7).rebirthing therapies, which engage people in reenacting their supposed birth trauma.

conversion therapies, which aim to enable homosexuals to change their sexual orientation.

It is as true for psychological treatments as it is for medical treatments—

This list of discredited therapies raises another question. Who should decide which psychotherapies get prizes and which do not? What role should science play in clinical practice, and how much should science guide health care providers and insurers in setting payment policies for psychotherapy?

This question lies at the heart of a controversy—

On the other side are the nonscientist therapists who view their practices as more art than science. They view psychotherapy as something that cannot be described in a manual or tested in an experiment. People are too complex and psychotherapy is too intuitive for a one-

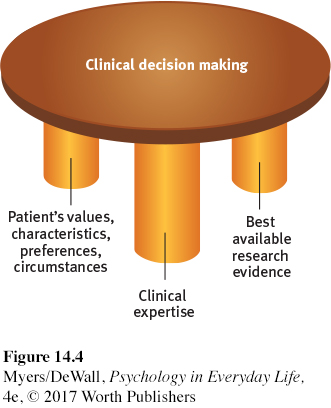

evidence-

Between these two camps stand the science-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 14.9

•Therapy is most likely to be helpful for those with problems that (are/are not) well defined.

ANSWER: are

Question 14.10

•What is evidence-

ANSWER: Using this approach, therapists make decisions about treatment based on research evidence, clinical expertise, and knowledge of the patient.

How Do Psychotherapies Help People?

LOQ 14-

Why do therapists’ training and experience have so little influence on clients’ outcomes? The answer seems to be that all psychotherapies offer three basic benefits (Frank, 1982; Goldfried & Padawer, 1982; Strupp, 1986; Wampold, 2001, 2007). They all offer hope for demoralized people; a new perspective on oneself and the world; and an empathic, trusting, caring relationship.

HOPE FOR DEMORALIZED PEOPLE Many people seek therapy because they feel anxious, depressed, self-

A NEW PERSPECTIVE Every psychotherapy also offers people an explanation of their symptoms. Psychotherapy is a new experience that can help people change their behavior and their view of themselves. Armed with a believable fresh perspective, people may approach life with new energy to make needed changes.

therapeutic alliance a bond of trust and mutual understanding between a therapist and client, who work together constructively to overcome the client’s problem.

AN EMPATHIC, TRUSTING, CARING RELATIONSHIP No matter what technique they use, effective psychotherapists are empathic. They seek to understand people’s experiences. They communicate care and concern. And they earn trust through respectful listening, reassurance, and guidance. These qualities were clear in recorded therapy sessions from 36 recognized master therapists (Goldfried et al., 1998). Some took a cognitive-

These three basic benefits—

* * *

To recap, people who seek psychotherapy usually improve. So do many of those who do not undergo psychotherapy, and that is a tribute to our human resourcefulness and our capacity to care for one another. Nevertheless, though the therapist’s orientation and experience appear not to matter much, people who receive some psychotherapy usually improve more than those who do not. People with clear-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 14.11

•Those who undergo psychotherapy are ________ (more/less) likely to show improvement than those who do not undergo psychotherapy.

ANSWER: more

How Do Culture and Values Influence Psychotherapy?

LOQ 14-

All psychotherapies offer hope. Nearly all psychotherapists try to enhance their clients’ sensitivity, openness, personal responsibility, and sense of purpose (Jensen & Bergin, 1988). But in matters of culture and values, psychotherapists differ from one another and may differ from their clients (Delaney et al., 2007; Kelly, 1990).

These differences can create a mismatch when a therapist from one culture interacts with a client from another. In North America, Europe, and Australia, for example, many psychotherapists reflect the majority culture’s individualism, which often gives priority to personal desires and identity. Clients with a collectivist perspective, as found in many Asian cultures, may assume people will be more mindful of social and family responsibilities, harmony, and group goals. These clients may have trouble relating to therapies that require them to think only of their individual well-

Cultural differences help explain some groups’ reluctance to use mental health services. People living in “cultures of honor” prize being strong and tough. They may feel that seeking mental health care is an admission of weakness (Brown et al., 2014b). And some minority groups tend to be both reluctant to seek therapy and quick to leave it (Broman, 1996; Chen et al., 2009; Sue, 2006). In one experiment, Asian-

Client-

Finding a Mental Health Professional

LOQ 14-

Life for everyone is marked by a mix of calm and stress, blessings and losses, good moods and bad. So when should we seek a mental health professional’s help? APA offers these common trouble signals:

Feelings of hopelessness

Deep and lasting depression

Self-

destructive behavior, such as substance abuse Disruptive fears

Sudden mood shifts

Thoughts of suicide

Compulsive rituals, such as hand washing

Sexual difficulties

Hearing voices or seeing things that others don’t experience

In looking for a psychotherapist, you may want to have a preliminary meeting with two or three. College health centers are generally good starting points, and they offer some free services. In your meeting, you can describe your problem and learn each therapist’s treatment approach. You can ask questions about the therapist’s values, credentials (TABLE 14.2), and fees. And you can assess your own feelings about each therapist. The emotional bond between therapist and client is perhaps the most important factor in effective therapy.

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Clinical psychologists | Most are psychologists with a Ph.D. (includes research training) or Psy.D. (focuses on therapy), supplemented by a supervised internship and, often, postdoctoral training. About half work in agencies and institutions, half in private practice. |

| Psychiatrists | Psychiatrists are physicians who specialize in the treatment of psychological disorders. Not all psychiatrists have had extensive training in psychotherapy, but as M.D.s or D.O.s they can prescribe medications. Thus, they tend to see those with the most serious problems. Many have their own private practice. |

| Clinical or psychiatric social workers | A two- |

| Counselors | Marriage and family counselors specialize in problems arising from family relations. Clergy provide counseling to countless people. Abuse counselors work with substance abusers and with spouse and child abusers and their victims. Mental health and other counselors may be required to have a two- |

The American Psychological Association recognizes the importance of a strong therapeutic alliance and it welcomes diverse therapists who can relate well to diverse clients. It accredits programs that provide training in cultural sensitivity (for example, to differing values, communication styles, and language) and that recruit underrepresented cultural groups.