2.6 Brain States and Consciousness

LOQ 2-

consciousness our awareness of ourselves and our environment.

Consciousness is our awareness of ourselves and our environment (Paller & Suzuki, 2014). Consciousness enables us to exert voluntary control and to communicate our mental states to others. When we learn a complex concept or behavior, it is consciousness that focuses our attention. It lets us assemble information from many sources as we reflect on the past, adapt to the present, and plan for the future.

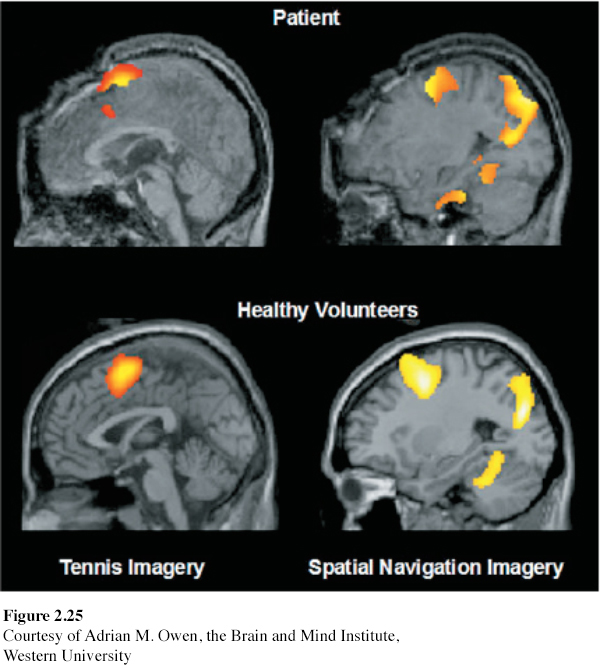

Can consciousness persist in a permanently motionless body? Possibly, depending on the underlying condition. A hospitalized 23-

“I am a brain, Watson. The rest of me is a mere appendix.”

Sherlock Holmes, in Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Adventure of the Mazarin Stone,” 1921

Consciousness is not located in any one small brain area. Conscious awareness is a product of coordinated, brain-

sequential processing the processing of one aspect of a problem at a time; used when we focus attention on new or complex tasks.

parallel processing the processing of many aspects of a problem simultaneously; the brain’s natural mode of information processing for many functions.

When we consciously focus on a new or complex task, our brain uses sequential processing, giving full attention to one thing at a time. But sequential processing is only one track in the two-

In addition to normal waking awareness, consciousness comes to us in altered states, aspects of which are discussed in other chapters—

Selective Attention

selective attention focusing conscious awareness on a particular stimulus.

Your conscious awareness focuses, like a flashlight beam, on a very small part of all that you experience. Psychologists call this selective attention. Until reading this sentence, you were unaware that your nose is jutting into your line of vision. Now, suddenly, the spotlight shifts, and your nose stubbornly intrudes on the words before you. While focusing on these words, you’ve also been blocking other parts of your environment from awareness, though your normal side vision would let you see them easily. You can change that. As you stare at the X below, notice what surrounds these sentences (the edges of the page, the desktop, the floor).

X

Chat on your phone, text, or tweak your playlist while driving, and your selective attention will shift back and forth between the road and its electronic competition. Indeed, it shifts more than we realize. One study left people in a room for 28 minutes, free to surf the Internet and to control and watch a TV. How many times did their attention shift between the two? Participants guessed it was about 15 times. Not even close! The actual number (verified by eye-

“Has a generation of texters, surfers, and twitterers evolved the enviable ability to process multiple streams of novel information in parallel? Most cognitive psychologists doubt it.”

Steven Pinker, “Not at All,” 2010

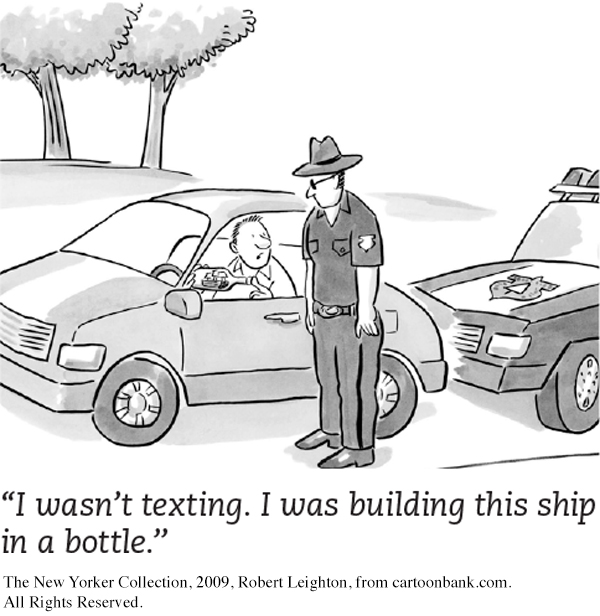

Rapid toggling between activities is today’s great enemy of sustained, focused attention. When we switch attentional gears, especially when we shift complex tasks like noticing and avoiding cars around us, we pay a toll—

When a driver attends to a conversation, activity in brain areas vital to driving decreases an average of 37 percent (Just et al., 2008). Chatting or texting—

Talking is distracting, but texting wins the danger game. In an 18-

Visit LaunchPad to watch the thought-

Visit LaunchPad to watch the thought-

inattentional blindness failing to see visible objects when our attention is directed elsewhere.

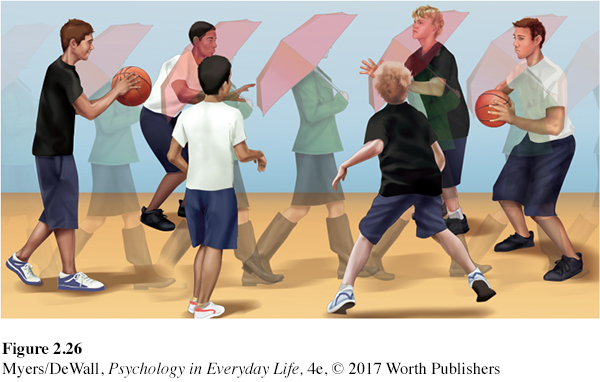

Our conscious attention is so powerfully selective that we become “blind” to all but a tiny sliver of the immense ocean of visual stimuli constantly before us. In one famous study, people watched a one-

The invisible gorilla struck again in a study of 24 radiologists who were asked to search for signs of cancer in lung scans. All but 4 of them missed the little image of a gorilla embedded in the scan (Drew et al., 2013). They did, however, spot the much tinier groups of cancer cells, which were the focus of their attention.

Given that most of us miss people strolling by in gorilla suits while our attention is focused elsewhere, imagine the fun that others can have by distracting us. Misdirect our attention and we will miss the hand slipping into the pocket. “Every time you perform a magic trick, you’re engaging in experimental psychology,” says magician Teller, a master of mind-

change blindness failing to notice changes in the environment; a form of inattentional blindness.

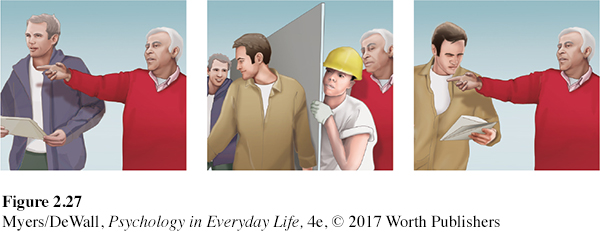

Magicians also exploit our change blindness (a form of inattentional blindness). With a dramatic flourish, they direct our selective attention away from other changes being made. So, too, in laboratory experiments, where viewers failed to notice that, after a brief visual interruption, a big Coke bottle had disappeared, a railing had risen, clothing had changed color—

For more on change blindness, watch the 3-

For more on change blindness, watch the 3-

The point to remember: Our conscious mind is in one place at a time. But outside our conscious awareness, the other track of our two-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 2.20

•Explain three attentional principles that magicians may use to fool us.

ANSWER: Our selective attention allows us to focus on only a limited portion of our surroundings. Inattentional blindness explains why we don’t perceive some things when we are distracted. And change blindness happens when we fail to notice a relatively unimportant change in our environment. All these principles help magicians fool us, as they direct our attention elsewhere to perform their tricks.

Sleep and Dreams

Each night, we lose consciousness and slip into sleep. We may feel “dead to the world,” but we are not. Our perceptual window remains open a crack, and our two-

Sleep’s mysteries puzzled scientists for centuries. Now, in laboratories around the world, some of these mysteries are being solved as people sleep, attached to recording devices, while others observe. By recording brain waves and muscle movements, and by watching and sometimes waking sleepers, researchers are glimpsing things that a thousand years of common sense never told us.

Biological Rhythms and Sleep

LOQ 2-

Like the ocean, life has its rhythmic tides. Let’s look more closely at two of these biological rhythms—

circadian [ser-

CIRCADIAN RHYTHM Try pulling an all-

Age and experience can alter our circadian rhythm. Most 20-

REM sleep rapid eye movement sleep; a recurring sleep stage during which vivid dreams commonly occur. Also known as paradoxical sleep, because the muscles are relaxed (except for minor twitches) but other body systems are active.

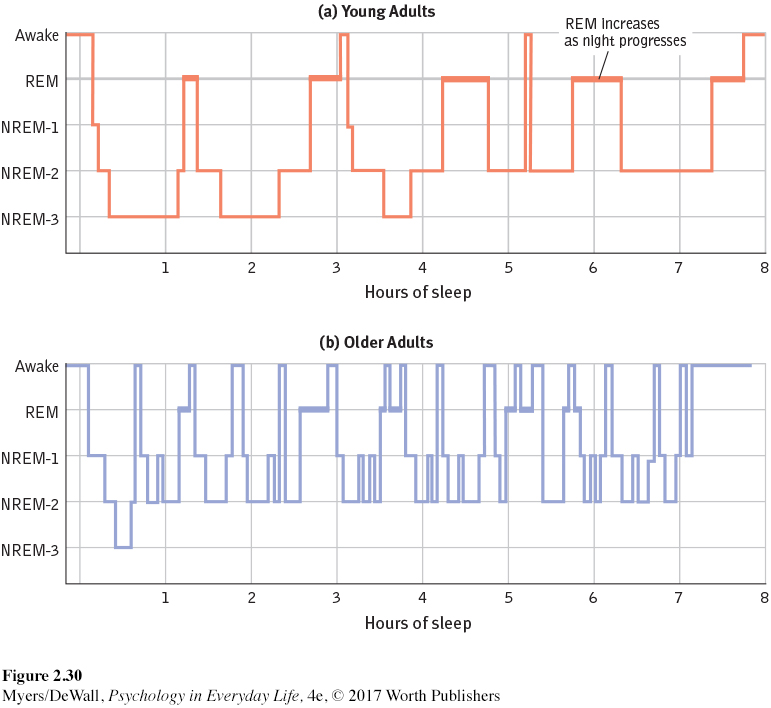

SLEEP STAGES Sooner or later, sleep overtakes us all, and consciousness fades as different parts of our brain’s cortex stop communicating (Massimini et al., 2005). Yet the sleeping brain is active and has its own biological rhythm. About every 90 minutes, we cycle through distinct sleep stages. This basic fact came to light after 8-

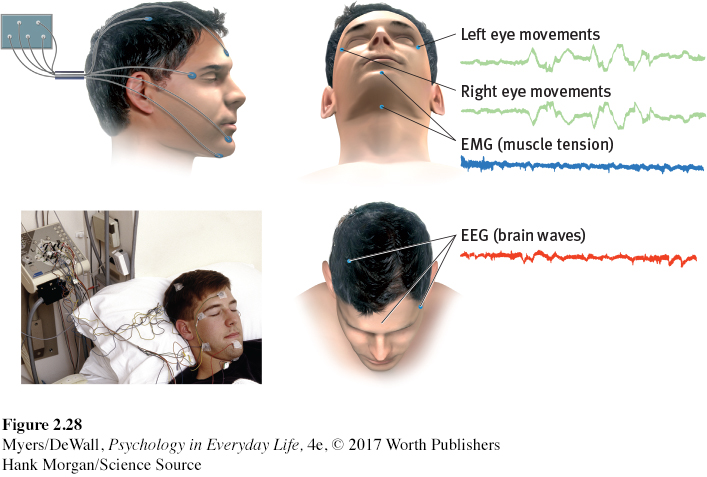

Similar procedures used with thousands of volunteers showed the cycles were a normal part of sleep (Kleitman, 1960). To appreciate these studies, imagine yourself as a participant. As the hour grows late, you feel sleepy and get ready for bed. A researcher comes in and tapes electrodes to your scalp (to detect your brain waves), on your chin (to detect muscle tension), and just outside the corners of your eyes (to detect eye movements) (FIGURE 2.28). Other devices will record your heart rate, breathing rate, and genital arousal.

alpha waves relatively slow brain waves of a relaxed, awake state.

sleep a periodic, natural loss of consciousness—

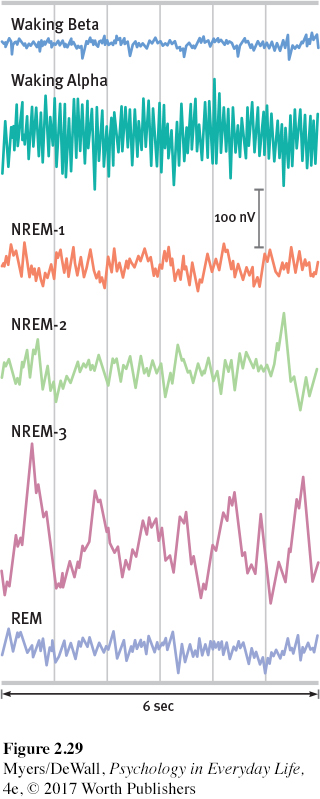

When you are in bed with your eyes closed, the researcher in the next room sees on the EEG the relatively slow alpha waves of your awake but relaxed state (FIGURE 2.29). As you adapt to all this equipment, you grow tired. Then, in a moment you won’t remember, your breathing slows and you slip into sleep. The EEG now shows the irregular brain waves of the non-

During this brief NREM-

You then relax more deeply and begin about 20 minutes of NREM-

delta waves large, slow brain waves associated with deep sleep.

Then you enter the deep sleep of NREM-

To better understand EEG readings and their relationship to consciousness, sleep, and dreams, experience the tutorial and simulation at LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: EEG and Sleep Stages.

To better understand EEG readings and their relationship to consciousness, sleep, and dreams, experience the tutorial and simulation at LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: EEG and Sleep Stages.

REM SLEEP About an hour after you first dive into sleep, a strange thing happens. You reverse course. From NREM-

Except during very scary dreams, your genitals become aroused during REM sleep. You have an erection or increased vaginal lubrication and clitoral engorgement, regardless of whether the dream’s content is sexual (Karacan et al., 1966). Men’s common “morning erection” stems from the night’s last REM period, often just before waking. (Many men who have occasional erectile problems get sleep-

During REM sleep, your brain’s motor cortex is active but your brainstem blocks its messages. This leaves your muscles relaxed, so much so that, except for an occasional finger, toe, or facial twitch, you are essentially paralyzed. Moreover, you cannot easily be awakened. REM sleep is thus sometimes called paradoxical sleep. The body is internally aroused, with waking-

Horses, which spend 92 percent of each day standing and can sleep standing, must lie down for muscle-

As the night goes on, the 90-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 2.21

•Why would communal sleeping provide added protection for these soldiers?

ANSWER: Each soldier cycles through the sleep stages independently. So, it is very likely that at any given time, at least one will be in an easily awakened stage in the event of a threat.

Question 2.22

•What are the four sleep stages, and in what order do we normally travel through those stages?

ANSWER: REM, NREM-

Question 2.23

•Can you match the cognitive experience with the sleep stage?

NREM-

1 NREM-

3 REM

story-

like dreams fleeting images

minimal awareness

ANSWERS: 1. b, 2. c, 3. a

Why Do We Sleep?

LOQ 2-

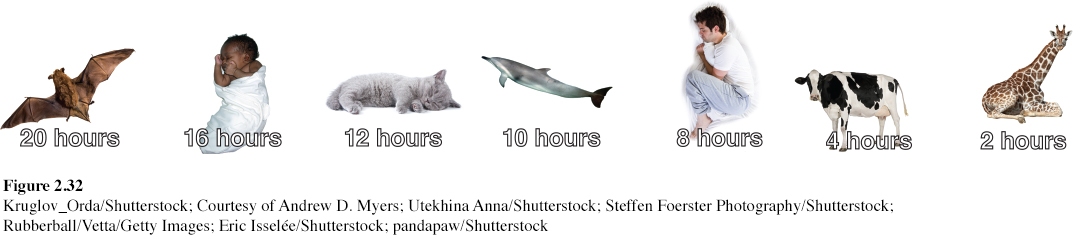

True or false? “Everyone needs 8 hours of sleep.” False. The first clue to how much sleep a person needs is their age. Newborns often sleep two-

Some adults thrive on fewer than 6 hours a night. Others regularly rack up 9 hours or more. Some of us are awake between nightly sleep periods, breaking the night into a “first sleep” and a “second sleep” (Randall, 2012). And for those who can nap, a 15-

In a 2013 Gallup poll, 40 percent of Americans reported getting 6 hours or less sleep at night (Jones, 2013).

But let’s not forget another of this book’s Big Ideas: Biological, psychological, and social-

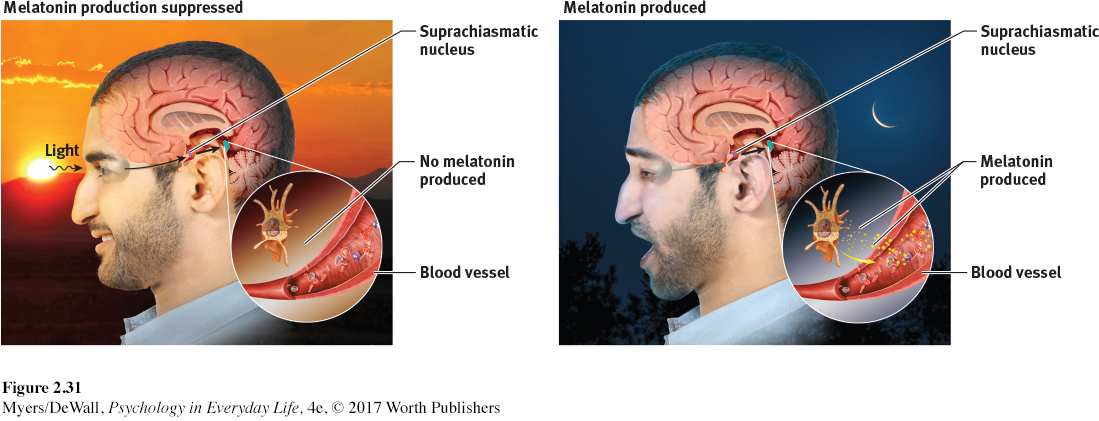

suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) a pair of cell clusters in the hypothalamus that controls circadian rhythm. In response to light, the SCN adjusts melatonin production, thus modifying our feelings of sleepiness.

Whether for work or play, bright light can disrupt our biological clock, tricking the brain into thinking night is morning. The process begins in our eyes’ retinas, which contain light-

SLEEP THEORIES So our sleep patterns differ from person to person and from culture to culture. But why do we need to sleep? Psychologists offer five possible reasons.

Sleep protects. When darkness shut down the day’s hunting, gathering, and social activities, our distant ancestors were better off asleep in a cave, out of harm’s way. Those who didn’t wander around dark cliffs were more likely to leave descendants. This fits a broader principle: Sleep patterns tend to suit a species’ place in nature. Animals with the greatest need to graze and the least ability to hide tend to sleep less (see FIGURE 2.32). Animals also sleep less, with no ill effects, during times of mating and migration (Siegel, 2012).

Sleep helps us recover. Sleep helps restore the immune system and repair brain tissue. Bats and many other small animals burn a lot of calories, producing free radicals, molecules that are toxic to neurons. Sleep sweeps away this toxic waste (Xie et al., 2013). Sleeping gives resting neurons time to repair, rewire, and reorganize themselves (Gilestro et al., 2009; Tononi & Cirelli, 2013). Think of it this way: When consciousness leaves your house, workers come in for a makeover, saying “Good night. Sleep tidy.”

Sleep helps us restore and rebuild fading memories of the day’s experiences. Sleep strengthens neural connections and replays recent learning (Yang et al., 2014). During sleep, the brain shifts memories from temporary storage in the hippocampus to permanent storage in areas of the cortex (Diekelmann & Born, 2010; Racsmány et al., 2010). Children and adults trained to perform tasks recall them better after a night’s sleep, or even after a short nap, than after several hours awake (Friedrich et al., 2015; Kurdziel et al., 2013; Stickgold & Ellenbogen, 2008). Sleep, it seems, strengthens memories in a way that being awake does not.

Page 58Sleep feeds creative thinking. A full night’s sleep boosts our thinking and learning. After working on a task, then sleeping on it, people solve problems more insightfully than do those who stay awake (Barrett, 2011; Sio et al., 2013). They also are better at spotting connections among novel pieces of information (Ellenbogen et al., 2007). To think smart and see connections, it often pays to sleep on it.

“Sleep faster, we need the pillows.”

Yiddish proverb

Sleep supports growth. During deep sleep, the pituitary gland releases a hormone we need for muscle development. A regular full night’s sleep can “dramatically improve your athletic ability” (Maas & Robbins, 2010). Well-

rested athletes have faster reaction times, more energy, and greater endurance. Teams that build 8 to 10 hours of daily sleep into their training show improved performance.

Given all the benefits of sleep, it’s no wonder that sleep loss—

Retrieve + Remember

Question 2.24

•What five theories explain our need for sleep?

ANSWER: (1) Sleep has survival value. (2) Sleep helps restore the immune system and repair brain tissue. (3) During sleep we strengthen memories. (4) Sleep fuels creativity. (5) Sleep plays a role in the growth process.

Sleep Deprivation and Sleep Disorders

LOQ 2-

Sleep commands roughly one-

THE EFFECTS OF SLEEP LOSS Today, more than ever, our sleep patterns leave us not only sleepy but drained of energy and feelings of well-

College students are especially sleep deprived. In one national survey, 69 percent reported “feeling tired” or “having little energy” on at least several days in the two previous weeks (AP, 2009). Small wonder so many fall asleep in class. The going needn’t get boring for students to start snoring.

To see whether you are one of the many sleep-

To see whether you are one of the many sleep-

Sleep loss also affects our mood. Tired often equals crabby—

Chronic sleep loss can suppress the immune system, lowering our resistance to illness. With fewer immune cells, we are less able to battle viral infections and cancer (Möller-

When sleepy frontal lobes confront visual attention tasks, reactions slow and errors increase (Caldwell, 2012; Lim & Dinges, 2010). For drivers in an unexpected situation, slow responses can spell disaster. Drowsy driving has contributed to an estimated one of six deadly American traffic accidents (AAA, 2010). One 2-

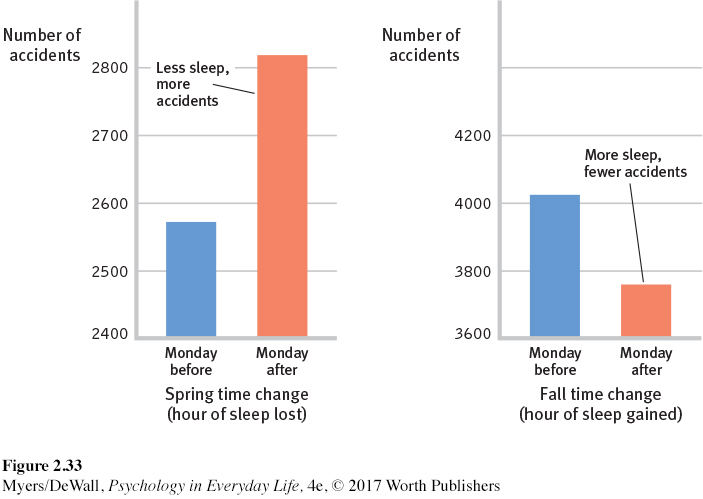

Deliberate manipulation of driver fatigue on the road would be illegal and unethical. But twice each year, most North Americans participate in a revealing sleep-

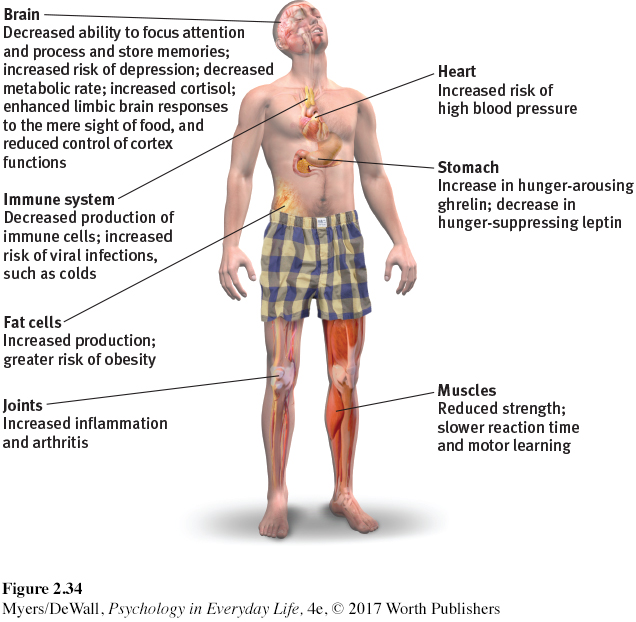

So sleep loss can destroy our mood, lower our resistance to infection, and decrease driver safety. It can also make us gain weight. Children and adults who sleep less than normal are heavier than average. And in recent decades, people have been sleeping less and weighing more (Shiromani et al., 2012). Here’s how it happens. Sleep deprivation

increases ghrelin, a hunger-

arousing hormone, and decreases its hunger- suppressing partner, leptin (Shilsky et al., 2012). decreases metabolic rate, a gauge of energy use (Buxton et al., 2012).

increases production of cortisol, a stress hormone that triggers fat production.

enhances limbic brain responses to the mere sight of food (Benedict et al., 2012; Greer et al., 2013; St-

Onge et al., 2012).

These effects may help explain the weight gain common among sleep-

FIGURE 2.34 summarizes the effects of sleep deprivation. But there is good news! Psychologists have discovered a treatment that strengthens memory, increases concentration, boosts mood, moderates hunger, reduces obesity, fortifies the disease-

Some students sleep like the fellow who stayed up all night to see where the Sun went. (Then it dawned on him.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

insomnia recurring problems in falling or staying asleep.

narcolepsy a sleep disorder in which a person has uncontrollable sleep attacks, sometimes lapsing directly into REM sleep.

sleep apnea a sleep disorder in which a sleeping person repeatedly stops breathing until blood oxygen is so low the person awakens just long enough to draw a breath.

MAJOR SLEEP DISORDERS Do you have trouble sleeping when anxious or excited? Most of us do. (Warning: A smart phone tucked under your pillow as an alarm clock increases the likelihood that you’ll have a bad night’s sleep.) An occasional loss of sleep is nothing to worry about. But for those who have a major sleep disorder—

| Disorder | Rate | Description | Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insomnia | 1 in 10 adults; 1 in 4 older adults | Ongoing difficulty falling or staying asleep. | Chronic tiredness. Reliance on sleeping pills and alcohol, which reduce REM sleep and lead to tolerance— |

| Narcolepsy | 1 in 2000 adults | Sudden attacks of overwhelming sleepiness. | Risk of falling asleep at a dangerous moment. Narcolepsy attacks usually last less than 5 minutes, but they can happen at the worst and most emotional times. Everyday activities, such as driving, require extra caution. |

| Sleep apnea | 1 in 20 adults | Stopping breathing repeatedly while sleeping. | Fatigue and depression (as a result of slow- |

| Sleepwalking/sleeptalking | 1– |

Doing normal waking activities (sitting up, walking, speaking) during NREM- |

Few serious concerns. People return to their beds on their own or with the help of a family member, rarely remembering their trip the next morning. |

| Night terrors | 1 in 100 adults; 1 in 30 children | Appearing terrified, talking nonsense, sitting up, or walking around during NREM- |

Doubling of a child’s heart and breathing rates during the attack. Luckily, children remember little or nothing of the fearful event the next day. As people age, night terrors become more and more rare. |

Dreams

LOQ 2-

Now playing at an inner theater near you: the premiere showing of a sleeping person’s dream. This never-

dream a sequence of images, emotions, and thoughts passing through a sleeping person’s mind.

REM dreams are vivid, emotional, and often bizarre (Loftus & Ketcham, 1994). Waking from one, we may wonder how our brain can so creatively, colorfully, and completely construct this inner world. Caught for a moment between our dreaming and waking consciousness, we may even be unsure which world is real. A 4-

“I love to sleep. Do you? Isn’t it great? It really is the best of both worlds. You get to be alive and unconscious.”

Comedian Rita Rudner, 1993

Each of us spends about six years of our life in dreams—

WHAT WE DREAM Few REM dreams are sweet. For both women and men, 8 in 10 are bad dreams (Domhoff, 2007). Common themes are failing in an attempt to do something; being attacked, pursued, or rejected; or experiencing misfortune (Hall et al., 1982). Dreams with sexual imagery occur less often than you might think. In one study, only 1 in 10 dreams among young men and 1 in 30 among young women had sexual overtones (Domhoff, 1996). More commonly, our dreams feature people and places from the day’s nonsexual experiences (De Koninck, 2000).

A popular sleep myth: If you dream you are falling and hit the ground (or if you dream of dying), you die. Unfortunately, those who could confirm these ideas are not around to do so. Many people, however, have had such dreams and are alive to report them.

Our two-

WHY WE DREAM Dream theorists have proposed several explanations of why we dream, including these five:

To satisfy our own wishes. In 1900, Sigmund Freud offered what he thought was “the most valuable of all the discoveries it has been my good fortune to make.” He proposed that dreams act as a safety valve, discharging feelings that the dreamer could not express in public. He called the dream’s remembered story line its manifest content. For Freud, this apparent content was a censored, symbolic version of the dream’s underlying meaning—

the latent content, or unconscious drives and wishes that would be threatening if expressed directly. Although most dreams have no openly sexual imagery, Freud believed most adult dreams could be “traced back by analysis to erotic wishes.” Thus, a gun appearing in a dream could be a penis in disguise. manifest content according to Freud, the remembered story line of a dream.

latent content according to Freud, the underlying meaning of a dream.

Freud’s critics say it is time to wake up from Freud’s dream theory, which they regard as a scientific nightmare. Scientific studies offer “no reason to believe any of Freud’s specific claims about dreams and their purposes,” said dream researcher William Domhoff (2003). Maybe a dream about a gun is really just a dream about a gun. Legend has it that even Freud, who loved to smoke cigars, agreed that “sometimes, a cigar is just a cigar.” Other critics have noted that dreams could be interpreted in many different ways. Freud’s wish-

fulfillment theory of dreams has in large part given way to other theories. To file away memories. The information-

processing perspective proposes that dreams may help sift, sort, and secure the day’s events in our memory. Some studies support this view. When tested the day after learning a task, those who had slept undisturbed did better than those who had been deprived of both slow-wave and REM sleep (Stickgold, 2012). Brain scans confirm the link between REM sleep and memory. Brain regions that were active as rats learned to navigate a maze (or as people learned to identify the difference between objects) were active again later during REM sleep (Louie & Wilson, 2001; Maquet, 2001). So precise were these activity patterns that scientists could tell where in the maze the rat would be if awake.

Students, take note. Sleep researcher Robert Stickgold (2000) believes many students suffer from a kind of sleep bulimia, sleep deprived on weekdays and binge sleeping on the weekend. He warned, “If you don’t get good sleep and enough sleep after you learn new stuff, you won’t integrate it effectively into your memories.” That helps explain why high school students with top grades slept about 25 minutes longer each night than their lower-

achieving classmates (Wolfson & Carskadon, 1998). Sacrificing sleep time to study actually worsens academic performance by making it harder the next day to understand class material or do well on a test (Gillen- O’Neel et al., 2013). To develop and preserve neural pathways. Dreams—

the brain activity linked to REM sleep— may give the sleeping brain a workout that helps it develop. As we’ll see in Chapter 3, stimulating experiences preserve and expand the brain’s neural pathways. Infants, whose neural networks are fast developing, spend much of their abundant sleep time in REM sleep. To make sense of neural static. Other theories propose that dreams are born when random neural activity spreads upward from the brainstem (Antrobus, 1991; Hobson, 2003, 2004, 2009). Our ever-

alert brain attempts to make sense of the activity, pasting the random bits of information into a meaningful image. Brain scans taken while people were dreaming have revealed increased activity in the emotion- related limbic system and in areas that process visual images (Schwarz, 2012). Damage either of these areas and dreaming itself may be impaired (Domhoff, 2003). Page 62To reflect cognitive development. Some dream researchers dispute these theories. Instead, they see dreams as a reflection of brain maturation and cognitive development (Domhoff, 2010, 2011; Foulkes, 1999). For example, before age 9, children’s dreams seem more like a slide show and less like an active story in which the child is an actor. Dreams at all ages tend to feature the kind of thinking and talking we demonstrate when awake. They seem to draw on our current knowledge and concepts we understand.

REM rebound the tendency for REM sleep to increase following REM sleep deprivation.

Despite their differences, today’s dream researchers agree on one thing: We need REM sleep. Deprived of it in sleep labs or in real life, people return more and more quickly to the REM stage when finally allowed to sleep undisturbed. They literally sleep like babies—

Retrieve + Remember

Question 2.25

•What five theories explain why we dream?

ANSWER: (1) Freud’s wish fulfillment (dreams as a psychic safety valve), (2) information processing (dreams sort the day’s events and form memories), (3) physiological function (dreams pave neural pathways), (4) making sense of neural static (REM sleep triggers random neural activity that the mind weaves into stories), (5) cognitive development (dreams reflect the dreamer’s developmental stage)

* * *

We have glimpsed the truth of this chapter’s overriding principle: Biological and psychological explanations of behavior are partners, not competitors. We are privileged to live in a time of breathtaking discovery about the interplay of our biology and our behavior and mental processes. Yet what is unknown still dwarfs what is known. We can describe the brain. We can learn the functions of its parts. We can study how the parts communicate. We can observe sleeping and waking brains. But how do we get mind out of meat? How does the electrochemical whir in a hunk of tissue the size of a head of lettuce give rise to a feeling of joy, a creative idea, or a crazy dream?

The mind seeking to understand the brain—