3.1 Developmental Psychology’s Major Issues

LOQ LearningObjectiveQuestion

3-

developmental psychology a branch of psychology that studies physical, cognitive, and social change throughout the life span.

Why do researchers find human development interesting? Like most of the rest of us, they want to understand more about how we’ve become our current selves, and how we may change in the years ahead. Developmental psychology examines our physical, cognitive, and social development across the life span, with a focus on three major issues:

Nature and nurture: How does our genetic inheritance (our nature) interact with our experiences (our nurture) to influence our development?

Continuity and stages: What parts of development are gradual and continuous, like riding an escalator? What parts change abruptly in separate stages, like climbing rungs on a ladder?

Stability and change: Which of our traits persist through life? How do we change as we age?

Nature and Nurture

The unique gene combination created when our mother’s egg absorbed our father’s sperm helped form us as individuals. Genes predispose both our shared humanity and our individual differences.

But it also is true that our experiences form us. Our families and peer relationships teach us how to think and act. Even differences initiated by our nature may be amplified by our nurture. We are not formed by either nature or nurture, but by the interaction between them. Biological, psychological, and social-

Mindful of how others differ from us, however, we often fail to notice the similarities stemming from our shared biology. Regardless of our culture, we humans share the same life cycle. We speak to our infants in similar ways and respond similarly to their coos and cries (Bornstein et al., 1992a,b). All over the world, the children of warm and supportive parents feel better about themselves and are less hostile than are the children of punishing and rejecting parents (Farruggia et al., 2004; Rohner, 1986; Scott et al., 1991). Although ethnic groups have differed in some ways, including average school achievement, the differences are “no more than skin deep” (Rowe et al., 1994). To the extent that family structure, peer influences, and parental education predict behavior in one of these ethnic groups, they do so for the others as well. Compared with the person-

Continuity and Stages

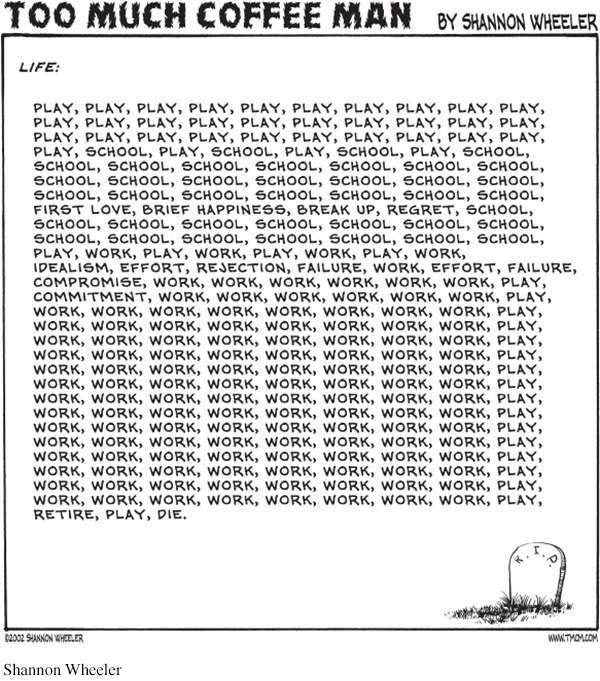

Do adults differ from infants as a giant redwood differs from its seedling—

Researchers who focus on experience and learning typically view development as a slow, ongoing process. Those who emphasize the influence of our biology tend to see development as a process of maturation, as we pass through a series of stages or steps, guided by instructions programmed into our genes. Progress through the various stages may be quick or slow, but we all pass through the stages in the same order.

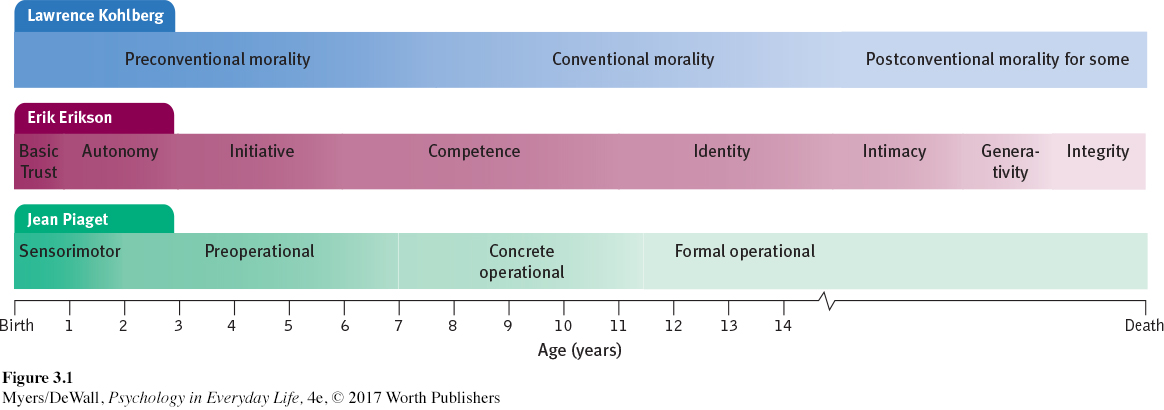

Are there clear-

Although many modern developmental psychologists do not identify as stage theorists, the stage concept remains useful. The human brain does experience growth spurts during childhood and puberty that correspond roughly to Piaget’s stages (Thatcher et al., 1987). And stage theories help us focus our attention on the forces and interests that affect us at different points in the life span. This close attention can help us understand how people of one age think and act differently when they arrive at a later age.

Stability and Change

As we follow lives through time, do we find more evidence for stability or change? If reunited with a long-

Developmental psychologists’ research shows that we experience both stability and change. People predict that they will not change much in the future (Quoidbach et al., 2013). In some ways, they are correct. Some of our characteristics, such as temperament (emotional excitability), are very stable. When a research team studied 1000 people from age 3 to 32, they were struck by the consistency of temperament and emotionality across time (Slutske et al., 2012). Out-

We cannot, however, predict all of our eventual traits based on our early years (Kagan, 1998; Kagan et al., 1978). Some traits, such as social attitudes, are much less stable than temperament, especially during the impressionable late adolescent years (Krosnick & Alwin, 1989; Rekker et al., 2015). And older children and adolescents can learn new ways of coping. It is true that delinquent children later have higher rates of work problems, substance abuse, and crime, but many confused and troubled children blossom into mature, successful adults (Moffitt et al., 2002; Roberts et al., 2001; Thomas & Chess, 1986). Happily for them, life is a process of becoming.

In some ways, we all change with age. Most shy, fearful toddlers begin opening up by age 4. In the years after adolescence, most people become more conscientious, self-

Life requires both stability and change. Stability increasingly marks our personality as we age (Briley & Tucker-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 3.1

•Developmental researchers who consider how biological, psychological, and social-

ANSWERS: nature; nurture

Question 3.2

•Developmental researchers who emphasize learning and experience are supporting _______; those who emphasize biological maturation are supporting _______.

ANSWERS: continuity; stages

Question 3.3

•What findings in psychology support (1) the stage theory of development and (2) the idea of stability in personality across the life span?

ANSWER: (1) Stage theory is supported by the work of Piaget (cognitive development), Kohlberg (moral development), and Erikson (psychosocial development). (2) Some traits, such as temperament, do exhibit remarkable stability across many years. But we do change in other ways, such as in our social attitudes.