3.5 Adulthood

The unfolding of our lives continues across the life span. Earlier in this chapter, we considered what we all share in life’s early years. Making such statements about the adult years is much more difficult. If we know that James is a 1-

Nevertheless, our life courses are in some ways similar. Physically, cognitively, and especially socially, we differ at age 60 from our 25-

Physical Development

LOQ 3-

Early Adulthood

Our physical abilities—

Middle Adulthood

During early and middle adulthood, physical vigor has less to do with age than with a person’s health and exercise habits. Sedentary 25-

Physical decline is gradual, but as most athletes know, the pace of that decline gradually picks up. As a lifelong basketball player, I [DM] find myself increasingly not racing for that loose ball. The good news is that even diminished vigor is enough for normal activities.

menopause the end of menstruation. In everyday use, it can also mean the biological transition a woman experiences from before until after the end of menstruation.

Aging also brings a gradual decline in fertility. For a 35-

Late Adulthood

Is old age “more to be feared than death” (Juvenal, Satires)? Or is life “most delightful when it is on the downward slope” (Seneca, Epistulae ad Lucilium)? What is it like to grow old?

Although physical decline begins in early adulthood, we are not usually acutely aware of it until later in life. Vision changes. We have trouble seeing fine details, and our eyes take longer to adapt to changes in light levels. As the eye’s pupil shrinks and its lens grows cloudy, less light reaches the retina—

Aging also levies a tax on the brain. The small, gradual net loss of brain cells begins in early adulthood. By age 80, the brain has lost about 5 percent of its former weight. Some of the brain regions that shrink during aging are the areas important for memory (Schacter, 1996; Ritchie et al., 2015). No wonder adults feel older after taking a memory test. “[It’s like] aging 5 years in 5 minutes,” joked one research team (Hughes et al., 2013). The frontal lobes, which help restrain impulsivity, also shrink, which helps explain older people’s occasional blunt questions (“Have you put on weight?”) or inappropriate comments (von Hippel, 2007, 2015). Happily for us, there is still some plasticity in the aging brain. It partly compensates for what it loses by recruiting and reorganizing neural networks (Park & McDonough, 2013).

“I am still learning.”

Michelangelo, 1560, at age 85

Up to the teen years, we process information with greater and greater speed (Fry & Hale, 1996; Kail, 1991). But compared with teens and young adults, older people take a bit more time to react, to solve perceptual puzzles, even to remember names (Bashore et al., 1997; Verhaeghen & Salthouse, 1997). This neural processing lag is greatest on complex tasks (Cerella, 1985; Poon, 1987). At video games, most 70-

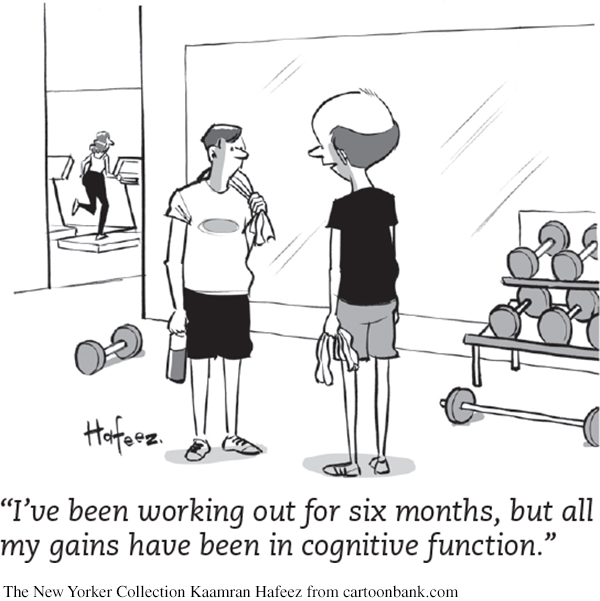

But there is some good news. A study of identical twin pairs—

Exercise also helps maintain the telomeres, which protect the ends of chromosomes (Erickson, 2009; Leslie, 2011; Loprinzi et al., 2015). With age, telomeres wear down, much as the tip of a shoelace frays. Smoking, obesity, or stress can speed up this wear. Children who suffer frequent abuse or bullying exhibit shortened telomeres as biological scars (Shalev et al., 2013). As telomeres shorten, aging cells may die without being replaced with perfect genetic copies (Epel, 2009).

The message is clear: We are more likely to rust from disuse than to wear out from overuse. Fit bodies support fit minds.

Muscle strength, reaction time, and stamina also diminish noticeably in late adulthood. The fine-

“The things that stop you having sex with age are exactly the same as those that stop you riding a bicycle (bad health, thinking it looks silly, no bicycle).”

Alex Comfort, The Joy of Sex, 2002

For those growing older, there is both bad and good news about health. The bad news: The body’s disease-

For both men and women, sexual activity also remains satisfying after middle age. When does sexual desire diminish? In one sexuality survey, age 75 was the point when most women and nearly half the men reported little sexual desire (DeLamater, 2012; DeLamater & Sill, 2005). In another study, 75 percent of those surveyed nevertheless reported being sexually active into their eighties (Schick et al., 2010).

Cognitive Development

Aging and Memory

LOQ 3-

As we age, we remember some things well. Looking back in later life, adults asked to recall the one or two most important events over the last half-

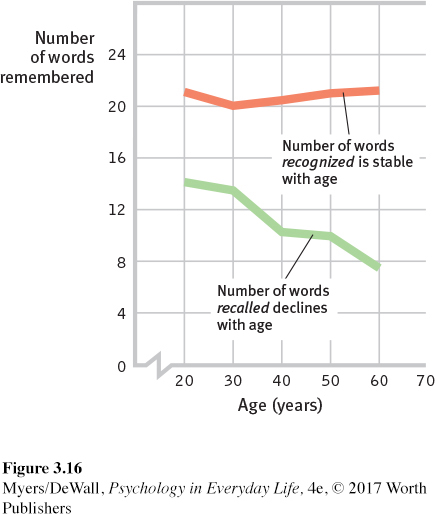

Early adulthood is indeed a peak time for some types of learning and remembering. Consider one experiment in which 1205 people were invited to learn some names (Crook & West, 1990). They watched video clips in which 14 strangers said their names, using a common format: “Hi, I’m Larry.” Then those strangers reappeared and gave additional details. For example, they said “I’m from Philadelphia,” which gave viewers more visual and voice cues for remembering the person’s name. After a second and third replay of the introductions, everyone remembered more names, but younger adults consistently remembered more names than older adults. How well older people remember depends in part on the task. When asked to recognize words they had earlier tried to memorize, people showed only a slight decline in memory. When asked to recall that information without clues, however, the decline was greater (FIGURE 3.16).

No matter how quick or slow we are, remembering seems also to depend on the type of information we are trying to retrieve. If the information is meaningless—

cross-

longitudinal study research in which the same people are restudied and retested over a long period.

See LaunchPad’s Video: Longitudinal and Cross-

See LaunchPad’s Video: Longitudinal and Cross-

Chapter 8 explores another dimension of cognitive development: intelligence. As we will see, cross-

Sustaining Mental Abilities

Psychologists who study the aging mind have been debating whether “brain-

Based on such findings, some computer game makers have been marketing daily brain-

Social Development

LOQ 3-

Adulthood’s Commitments

Two basic aspects of our lives dominate adulthood. Erik Erikson called them intimacy (forming close relationships) and generativity (being productive and supporting future generations). Sigmund Freud (1935/1960) put it most simply: The healthy adult, he said, is one who can love and work.

LOVE We typically flirt, fall in love, and commit—

Romantic attraction is often influenced by chance encounters (Bandura, 1982). Psychologist Albert Bandura (2005) recalled the true story of a book editor who came to one of Bandura’s lectures on the “Psychology of Chance Encounters and Life Paths”—and ended up marrying the woman who happened to sit next to him.

Bonds of love are most satisfying and enduring when two adults share similar interests and values and offer mutual emotional and material support. One of the ties that binds couples is self-

The chances that a marriage will last also increase when couples marry after age 20 and are well educated. Compared with their counterparts of 30 years ago, people in Western countries are better educated and marrying later (Wolfinger, 2015). These trends may help explain why the American divorce rate, which surged from 1960 to 1980, has since leveled off and even slightly declined in some areas (Schoen & Canudas-

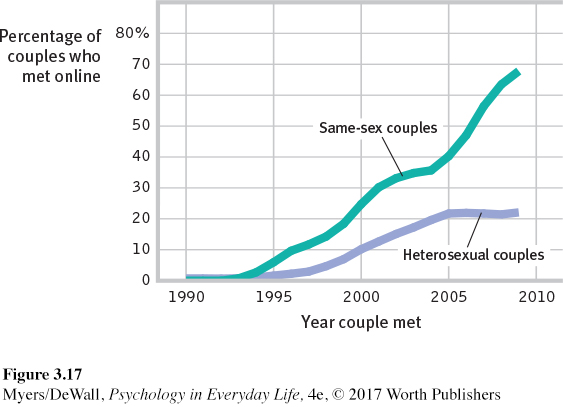

Historically, couples have met at school, on the job, or through family and friends. Thanks to the Internet, many couples now meet online. As one recent national survey revealed, nearly a quarter of heterosexual couples and some two-

Might test-

Nonetheless, the institution of marriage endures. Ninety-

Often, love bears children. For most people, this most enduring of life changes is a happy event—

Children eventually leave home. This departure is a significant and sometimes difficult event. But for most people, an empty nest is a happy place (Adelmann et al., 1989; Gorchoff et al., 2008). Many parents experience a “postlaunch honeymoon,” especially if they maintain close relationships with their children (White & Edwards, 1990). As Daniel Gilbert (2006) concluded, “The only known symptom of ‘empty nest syndrome’ is increased smiling.”

To explore the connection between parenting and happiness, visit LaunchPad’s IMMERSIVE LEARNING: How Would You Know If Having Children Relates to Being Happier?

To explore the connection between parenting and happiness, visit LaunchPad’s IMMERSIVE LEARNING: How Would You Know If Having Children Relates to Being Happier?

WORK Having work that fits your interests provides a sense of competence and accomplishment. For many adults, the answer to “Who are you?” depends a great deal on the answer to “What do you do?” Choosing a career path is difficult, especially during bad economic times. (See Appendix B: Psychology at Work for more on building work satisfaction.)

social clock the culturally preferred timing of social events such as marriage, parenthood, and retirement.

For both men and women, there exists a social clock—a culture’s definition of “the right time” to leave home, get a job, marry, have children, and retire. It’s the expectation people have in mind when saying “I married early” or “I started college late.” Today the clock still ticks, but people feel freer about keeping their own time.

Well-Being Across the Life Span

LOQ 3-

To live is to grow older. This moment marks the oldest you have ever been and the youngest you will henceforth be. That means we all can look back with satisfaction or regret, and forward with hope or dread. When asked what they would have done differently if they could relive their lives, people most often answer, “taken my education more seriously and worked harder at it” (Kinnier & Metha, 1989; Roese & Summerville, 2005). Other regrets—

How will you look back on your life 10 years from now? Are you making choices that someday you will recollect with satisfaction?

From the teens to midlife, people’s sense of identity, confidence, and self-

Prior to the very end, however, the over-

“At 20 we worry about what others think of us. At 40 we don’t care what others think of us. At 60 we discover they haven’t been thinking about us at all.”

Anonymous

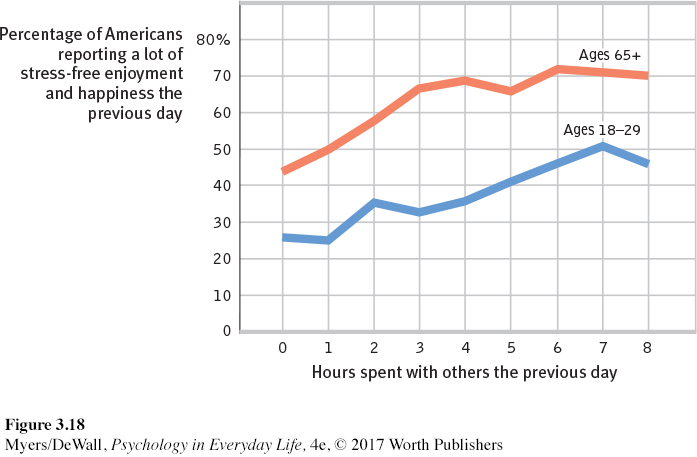

If anything, positive feelings, supported by better emotional control, tend to grow after midlife, and negative feelings decline (Stone et al., 2010; Urry & Gross, 2010). Compared with younger Chinese and American adults, older adults are more attentive to positive news (Isaacowitz, 2012; Wang et al., 2015b). Like people of all ages, older adults are happiest when not alone (FIGURE 3.18). Older adults experience fewer problems in their relationships—

Throughout the life span, the bad feelings tied to negative events fade faster than the good feelings linked with positive events (Walker et al., 2003). This leaves most older people with the comforting feeling that life, on balance, has been mostly good. As the years go by, feelings mellow (Brose et al., 2015). Highs become less high, lows less low.

Retrieve + Remember

Question 3.15

•Freud defined the healthy adult as one who is able to _______ and to _______.

ANSWERS: love; work

Death and Dying

LOQ 3-

Warning: If you begin reading the next paragraph, you will die.

But of course, if you hadn’t read this, you would still die in due time. Death is our unavoidable end. Most of us will also have to cope with the death of a close relative or friend. Normally, the most difficult separation is from the death of one’s spouse or partner—

Grief is especially severe when a loved one’s death comes suddenly and before its expected time. The sudden illness or accident that claims a 45-

For some, the loss is unbearable. One study tracked more than 17,000 people who had suffered the death of a child under 18. In the five years following that death, 3 percent of them were hospitalized for the first time in a psychiatric unit. This rate is 67 percent higher than the rate recorded for parents who had not lost a child (Li et al., 2005).

“Love—

Brian Moore, The Luck of Ginger Coffey, 1960

Why do grief reactions vary so widely? Some cultures encourage public weeping and wailing. Others expect mourners to hide their emotions. In all cultures, some individuals grieve more intensely and openly. Some popular beliefs, however, are not confirmed by scientific studies:

Those who immediately express the strongest grief do not purge their grief faster (Bonanno & Kaltman, 1999; Wortman & Silver, 1989). However, grieving parents who try to protect their partner by “staying strong” and not discussing their child’s death may actually prolong the grieving (Stroebe et al., 2013).

Grief therapy and self-

help groups offer support, but there is similar healing power in the passing of time, the support of friends, and the act of giving support and help to others (Baddeley & Singer, 2009; Brown et al., 2008; Neimeyer & Currier, 2009). After a spouse’s death, those who talk often with others or who receive grief counseling adjust about as well as those who grieve more privately (Bonanno, 2009; Stroebe et al., 2005). Terminally ill and grief-

stricken people do not go through identical stages, such as denial before anger (Friedman & James, 2008; Nolen- Hoeksema & Larson, 1999). Given similar losses, some people grieve hard and long, others grieve less (Ott et al., 2007).

Facing death with dignity and openness helps people complete the life cycle with a sense of life’s meaningfulness and unity—

Retrieve + Remember

Question 3.16

•What are some of the most significant challenges and rewards of growing old?

ANSWER: Challenges: decline of muscular strength, reaction times, stamina, sensory keenness, cardiac output, and immune system functioning. Risk of cognitive decline increases. Rewards: positive feelings tend to grow; negative emotions are less intense; and anger, stress, worry, and social-