4.1 Gender Development

LOQ LearningObjectiveQuestion

4-

sex in psychology, the biologically influenced characteristics by which people define male and female.

gender in psychology, the socially influenced characteristics by which people define men and women.

Simply said, your body defines your sex. Your mind defines your gender. But your mind’s understanding of gender arises from the interplay between your biology and your experiences (Eagly & Wood, 2013). Before we consider that interplay in more detail, let’s take a closer look at some ways that males and females are both similar and different.

How Are We Alike? How Do We Differ?

LOQ 4-

Whether male or female, each of us receives 23 chromosomes from our mother and 23 from our father. Of those 46 chromosomes, 45 are unisex—

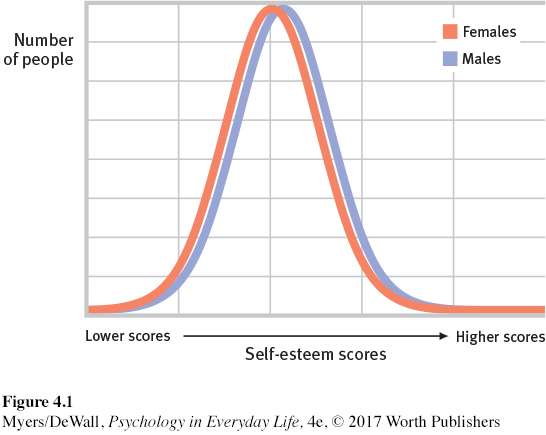

But in some areas, males and females do differ, and differences command attention. Some much-

Gender similarities and differences appear throughout this book. For now, let’s take a closer look at three gender differences. Although individuals vary greatly, the average male and female differ in aggression, social power, and social connectedness.

Aggression

aggression any act intended to harm someone physically or emotionally.

To a psychologist, aggression is any physical or verbal act intended to hurt someone (physically or emotionally). Think of some aggressive people you’ve heard or read about. Are most of them men? Likely yes. Men generally admit to more aggression, especially extreme physical violence (Bushman & Huesmann, 2010; Wölfer & Hewstone, 2015). In romantic relationships between men and women, minor acts of physical aggression, such as slaps, are roughly equal, but the most violent acts are usually committed by men (Archer, 2000; Johnson, 2008).

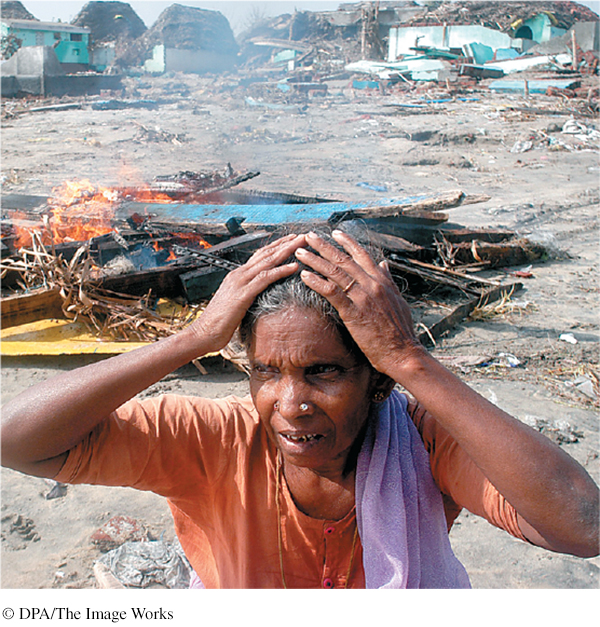

Laboratory experiments confirm a gender difference in aggression. Men have been more willing to blast people with what they believed was intense and prolonged noise (Bushman et al., 2007). The gender gap also appears outside the laboratory. Who commits more violent crimes worldwide? Men do (Antonaccio et al., 2011; Caddick & Porter, 2012; Frisell et al., 2012). Men also take the lead in hunting, fighting, warring, and supporting war (Liddle et al., 2012; Wood & Eagly, 2002, 2007).

relational aggression an act of aggression (physical or verbal) intended to harm a person’s relationship or social standing.

Here’s another question: Think of examples of people harming others by passing along hurtful gossip, or by shutting someone out of a social group or situation. Were most of those people men? Perhaps not. Those behaviors are acts of relational aggression, and women are slightly more likely than men to commit them (Archer, 2004, 2007, 2009).

Social Power

Imagine walking into a job interview. You sit down and peer across the table at your two interviewers. The unsmiling person on the left oozes self-

Which interviewer is male?

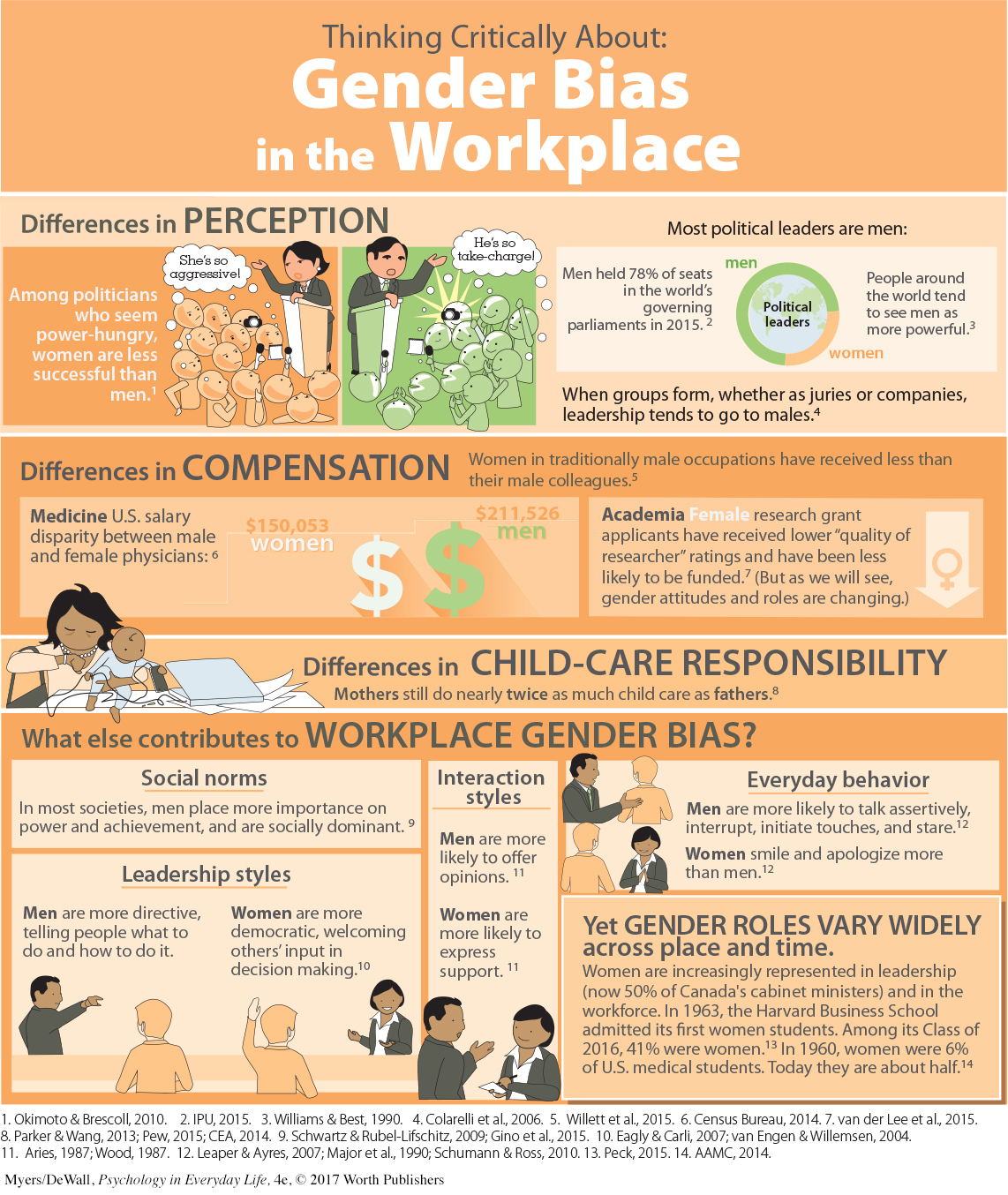

If you said the person on the left, you’re not alone. Around the world, from Nigeria to New Zealand, people have perceived gender differences in power (Williams & Best, 1990). Indeed, in most societies men do place more importance on power and achievement and are socially dominant (Gino et al., 2015; Schwartz & Rubel-

“Because it’s 2015.”

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, when asked why he chose a gender-

For more on this topic, see Thinking Critically About: Gender Bias in the Workplace.

Social Connectedness

Whether male or female, we humans cherish social connections. We all have a need to belong (more on this in Chapter 9).But males and females satisfy this need in different ways (Baumeister, 2010). Males tend to be independent. Even as children, males typically form large play groups. Boys’ games brim with activity and competition, with little intimate discussion (Rose & Rudolph, 2006). As adults, males enjoy side-

Scans of more than 1400 brains show no big differences between the sexes. “Human brains cannot be categorized into two distinct classes: male brain/female brain” (Joel et al., 2015). Brain scans do, however, suggest a subtle difference: A woman’s brain, more than a man’s, is wired in a way that enables social relationships (Ingalhalikar et al., 2013). This may help explain why females tend to be more interdependent. As children, they compete less and imitate social relationships more (Maccoby, 1990; Roberts, 1991). They usually play in small groups, often with one friend. As teens, girls spend less time alone and more time with friends (Wong & Csikszentmihalyi, 1991). Compared with their male counterparts, teen girls average twice as many daily texts and, in late adolescence, spend more time on social networking sites (Lenhart, 2012; Pryor et al., 2007, 2011). Girls’ and women’s friendships are more intimate, with more conversation that explores relationships (Maccoby, 2002).

More than a half-

Take a minute now to think about the last time you felt worried or hurt and wanted to talk with someone who would understand. Was that person male or female? At such times, most people turn to women, who are said to tend and befriend (Tamres et al., 2002; Taylor, 2002). They support others, and they, more than men, turn to others for support. Both men and women have reported that their friendships with women are more intimate, enjoyable, and nurturing (Kuttler et al., 1999; Rubin, 1985; Sapadin, 1988).

Gender differences in both social connectedness and power are greatest in late adolescence and early adulthood—

LOQ 4-

By age 50, most parenting-

So, although women and men are more alike than different, there are some behavior differences between the average woman and man. Are such differences dictated by our biology? Shaped by our cultures and other experiences? Do we vary in the extent to which we are male or female? Read on.

Retrieve + Remember

Question 4.1

•(Men/Women) are more likely to commit relational aggression, and (men/women) are more likely to commit physical aggression.

ANSWERS: Women; men

The Nature of Gender: Our Biological Sex

LOQ 4-

In many physical ways, men and women are similar. We sweat to cool down, guzzle an energy drink or coffee to get going in the morning, search for darkness and quiet to sleep. When looking for a mate, we also prize many of the same traits—

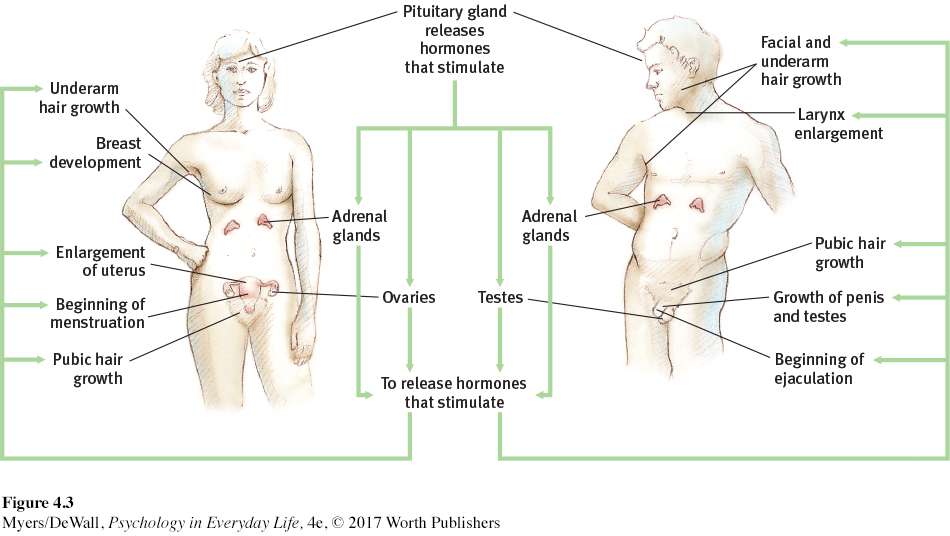

Biology does not dictate gender, but it can influence it in two ways:

Genetically—males and females have differing sex chromosomes.

Physiologically—males and females have differing concentrations of sex hormones, which trigger other anatomical differences.

These influences began to form you long before you were born.

Prenatal Sexual Development

X chromosome the sex chromosome found in both men and women. Females typically have two X chromosomes; males typically have one. An X chromosome from each parent produces a female child.

Y chromosome the sex chromosome typically found only in males. When paired with an X chromosome from the mother, it produces a male child.

Six weeks after you were conceived, you and someone of the other sex looked much the same. Then, as your genes kicked in, your biological sex became more apparent. Whether you are male or female, your mother’s contribution to your twenty-

testosterone the most important male sex hormone. Both males and females have it, but the additional testosterone in males stimulates the growth of the male sex organs during the fetal period and the development of the male sex characteristics during puberty.

About seven weeks after conception, a single gene on the Y chromosome throws a master switch. “Turned on,” this switch triggers the testes to develop and to produce testosterone, the main androgen (male hormone) that promotes male sex organ development. (Females also have testosterone, but less of it.) Later, during the fourth and fifth prenatal months, sex hormones bathe the fetal brain and tilt its wiring toward female or male patterns (Hines, 2004; Udry, 2000).

Adolescent Sexual Development

puberty the period of sexual maturation, when a person becomes capable of reproducing.

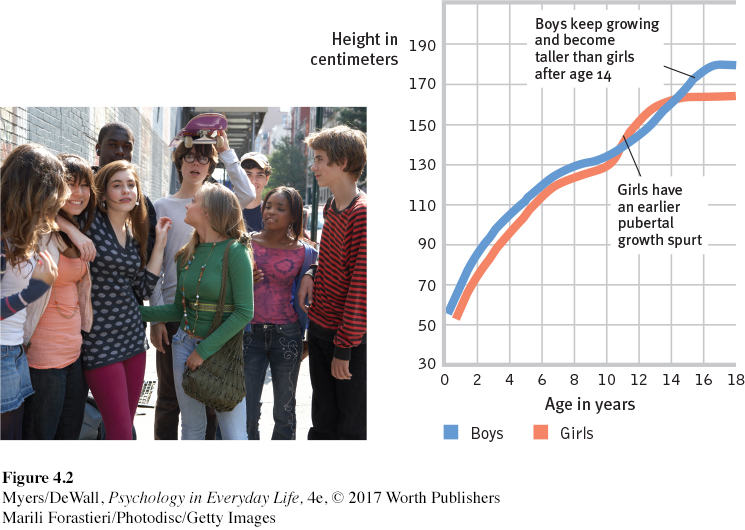

During adolescence, boys and girls enter puberty and mature sexually. A surge of hormones triggers a two-

primary sex characteristics the body structures (ovaries, testes, and external genitalia) that make sexual reproduction possible.

secondary sex characteristics nonreproductive sexual traits, such as female breasts and hips, male voice quality, and body hair.

Girls’ slightly earlier entry into puberty can at first propel them to greater height than boys of the same age (FIGURE 4.2). But boys catch up when they begin puberty, and by age 14 they are usually taller than girls. During these growth spurts, the primary sex characteristics—the reproductive organs and external genitalia—

Pubertal boys may not at first like their sparse beard. (But then it grows on them.)

spermarche [sper-

For boys, puberty’s landmark is the first ejaculation, which often occurs during sleep (as a “wet dream”). This event, called spermarche, usually happens by about age 14.

menarche [meh-

In girls, the landmark is the first menstrual period, menarche, usually within a year of age 12½ (Anderson et al., 2003). Genes play a major role in predicting when girls will have their first period (Perry et al., 2014). But environment matters, too. Early menarche is more likely following stresses related to father absence, sexual abuse, insecure attachments, or a history of a mother’s smoking during pregnancy (DelPriore & Hill, 2013; Rickard et al., 2014; Shrestha et al., 2011). In various countries, girls are developing breasts earlier (sometimes before age 10) and reaching puberty earlier than in the past. Suspected triggers include increased body fat, diets filled with hormone-

Girls prepared for menarche usually view it as a positive life transition (Chang et al., 2009). Most women recall the onset of their first menstrual period with mixed emotions—

Retrieve + Remember

Question 4.2

•Prenatal sexual development begins about __________ weeks after conception. Adolescence is marked by the onset of _________.

ANSWERS: seven; puberty

For a 7-

For a 7-

Sexual Development Variations

intersex a condition present at birth; possessing biological sexual characteristics of both sexes.

Nature may blur the biological line between males and females. Sometimes a fetus is exposed to unusual levels of sex hormones or is especially sensitive to those hormones. These intersex individuals may be born with unusual combinations of male and female chromosomes, hormones, and anatomy. A genetic male, for example, may be born with normal male hormones and testes but no penis or a very small one. Such individuals may struggle to identify their gender identity.

In the past, medical professionals often recommended sex-

These conditions raise the question: What makes a biological male or female? In 2015, this question made the sports pages when Indian sprinter Dutee Chand was found to have natural testosterone levels higher than most females. The International Association of Athletics Federations suspended Chand, forcing her to miss several events. The Court of Arbitration for Sport finally ruled in favor of Chand, allowing her to continue to compete as a woman.

In one famous case, a little boy lost his penis during a botched circumcision. His parents followed a psychiatrist’s advice to raise him as a girl rather than as a damaged boy. So, with male chromosomes and hormones and female upbringing, did nature or nurture form this child’s gender identity? Although raised as a girl, “Brenda” Reimer was not like most other girls. “She” didn’t like dolls. She tore her dresses with rough-

The Nurture of Gender: Our Culture and Experiences

LOQ 4-

For many people, biological sex and gender exist together in harmony. Biology draws the outline, and culture paints the details. The physical traits that define a newborn as male or female are the same worldwide. But the gender traits that define how men (or boys) and women (or girls) should act, interact, and feel about themselves differ from one time and place to another.

Gender Roles

role a set of expectations (norms) about a social position, defining how those in the position ought to behave.

gender role a set of expected behaviors, attitudes, and traits for males or for females.

Cultures shape our behaviors by defining how we ought to behave in a particular social position, or role. We can see this shaping power in gender roles— the social expectations that guide our behavior as men or as women. Gender roles shift over time and they differ from place to place.

In just a thin slice of history, gender roles have undergone an extreme makeover, worldwide. At the beginning of the twentieth century, only one country in the world—

Take a minute to check your own gender expectations. Would you agree that “When jobs are scarce, men should have more rights to a job”? In the United States, Britain, and Spain, a little over 12 percent of adults agree. In Nigeria, Pakistan, and India, about 80 percent of adults agree (Pew, 2010). This question taps people’s views on the idea that men and women should be treated equally. We’re all human, but my, how our views differ. Northern European countries offer the greatest gender equity, Middle Eastern and North African countries the least (UN, 2015).

“You cannot put women and men on an equal footing. It is against nature. They were created differently.”

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, President of Turkey, 2014

How Do We Learn Gender?

gender identity our sense of being male, female, or some combination of the two.

A gender role describes how others expect us to think, feel, and act. Our gender identity is our personal sense of being male, female, or, occasionally, some combination of the two. How do we develop that personal viewpoint?

social learning theory the theory that we learn social behavior by observing and imitating and by being rewarded or punished.

gender typing the acquisition of a traditional masculine or feminine role.

Social learning theory assumes that we acquire our gender identity in childhood, by observing and imitating others’ gender-

androgyny displaying both traditional masculine and feminine psychological characteristics.

Parents do help to transmit their culture’s views on gender. In one analysis of 43 studies, parents with traditional gender views were more likely to have gender-

How we feel matters, but so does how we think. Early in life, we all form schemas, or concepts that help us make sense of our world. Our gender schemas organize our experiences of male-

As young children, we were “gender detectives” (Martin & Ruble, 2004). Before our first birthday, we knew the difference between a male and female voice or face (Martin et al., 2002). After we turned 2, language forced us to label the world in terms of gender. English classifies people as he and she. Other languages classify objects as masculine (“le train”) or feminine (“la table”).

Once children grasp that two sorts of people exist—

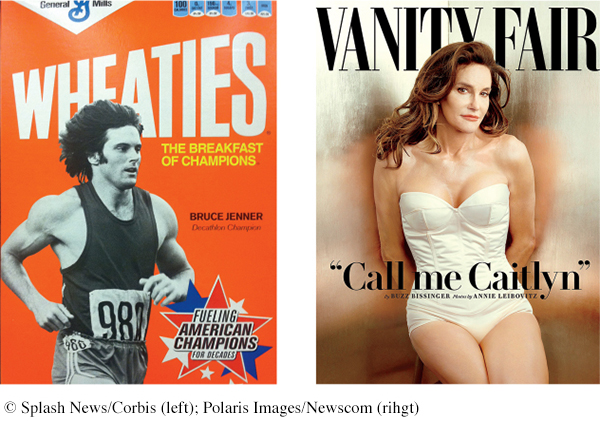

transgender an umbrella term describing people whose gender identity or expression differs from that associated with their birth sex.

For a transgender person, gender identity differs from the behaviors or traits considered typical for that person’s biological sex (APA, 2010; Bockting, 2014). From childhood onward, a person may feel like a male in a female body, or a female in a male body (Olson et al., 2015). In most countries, it’s not easy being transgender. In a national survey of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender Americans, 71 percent saw “some” or “a lot” of social acceptance for gay men, and 85 percent said the same for lesbians. But only 18 percent saw similar acceptance for transgender people (Sandstrom, 2015).

“The more I was treated as a woman, the more woman I became.”

Writer Jan Morris, male-

For a 6.5-

For a 6.5-

Transgender people may attempt to align their outward appearance with their internal gender identity by dressing as a person of the other biological sex typically would. Some transgender people are also transsexual: They prefer to live as members of the other birth sex. Brain scans reveal that those (about 75 percent men) who seek medical sex-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 4.3

•What are gender roles, and what do their variations tell us about our human capacity for learning and adaptation?

ANSWER: Gender roles are social rules or norms for accepted and expected male and female behaviors. Gender roles vary widely in different cultures and over time, which is proof that we are able to learn and adapt to the social demands of different environments.