5.4 Sensory Interaction

LOQ 5-

sensory interaction the principle that one sense may influence another, as when the smell of food influences its taste.

We have seen that vision and kinesthesia interact. Actually, all our senses eavesdrop on one another (Rosenblum, 2013). This is sensory interaction at work. One sense can influence another.

Consider how smell sticks its nose into the business of taste. Hold your nose, close your eyes, and have someone feed you various foods. You may be unable to tell a slice of apple from a chunk of raw potato. A piece of steak may taste like cardboard. Without their smells, a cup of cold coffee and a glass of red wine may seem the same. To savor a taste, we normally breathe the aroma through our nose—

Hearing and vision may similarly interact. We can see a tiny flicker of light more easily if it is paired with a short burst of sound (Kayser, 2007). The reverse is also true: We can hear soft sounds more easily if they are paired with a visual cue (FIGURE 5.29). If I [DM], a person with hearing loss, watch a video with on-

So our senses interact. But what happens if they disagree? What if our eyes see a speaker form one sound but our ears hear another sound? Surprise: Our brain may perceive a third sound that blends both inputs. Seeing mouth movements for ga while hearing ba, we may perceive da. This is known as the McGurk effect, after one of its discoverers (McGurk & MacDonald, 1976). For all of us, lip reading is part of hearing.

embodied cognition the influence of bodily sensations, gestures, and other states on cognitive preferences and judgments.

We have seen that our perceptions have two main ingredients: Our bottom-

Physical warmth may promote social warmth. After holding a warm drink rather than a cold one, people were more likely to rate someone more warmly, feel closer to them, and behave more generously (IJzerman & Semin, 2009; Williams & Bargh, 2008).

Social exclusion can literally feel cold. After being given the cold shoulder by others, people judged the room to be colder than did those who had been treated warmly (Zhong & Leonardelli, 2008).

Judgments of others may also mimic body sensations. Sitting at a wobbly desk and chair makes others’ relationships seem less stable (Kille et al., 2013).

Are you wondering how researchers test these kinds of questions? Try LaunchPad’s IMMERSIVE LEARNING: How Would You Know If a Cup of Coffee Can Warm Up Relationships?

Are you wondering how researchers test these kinds of questions? Try LaunchPad’s IMMERSIVE LEARNING: How Would You Know If a Cup of Coffee Can Warm Up Relationships?

As we attempt to decipher our world, our brain blends inputs from multiple channels. For many people, an odor—

* * *

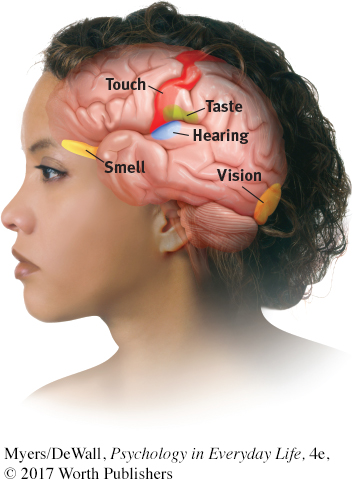

For a summary of our sensory systems, see TABLE 5.3.

| Sensory System | Source | Receptors | Key Brain Areas |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vision | Light waves striking the eye | Rods and cones in the retina | Occipital lobes |

| Hearing | Sound waves striking the outer ear | Cochlear hair cells in the inner ear | Temporal lobes |

| Touch | Pressure, warmth, cold, harmful chemicals | Receptors (nociceptors), mostly in the skin, which detect pressure, warmth, cold, and pain | Somatosensory cortex |

| Taste | Chemical molecules in the mouth | Basic tongue receptors for sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami | Frontal temporal lobe border |

| Smell | Chemical molecules breathed in through the nose | Millions of receptors at top of nasal cavities | Olfactory bulb |

| Body position— |

Any change in position of a body part, interacting with vision | Kinesthetic sensors in joints, tendons, and muscles | Cerebellum |

| Body movement— |

Movement of fluids in the inner ear caused by head/body movement | Hair- |

Cerebellum |