6.5 Learning by Observation

LOQ 6-

observational learning learning by observing others.

modeling the process of observing and imitating a specific behavior.

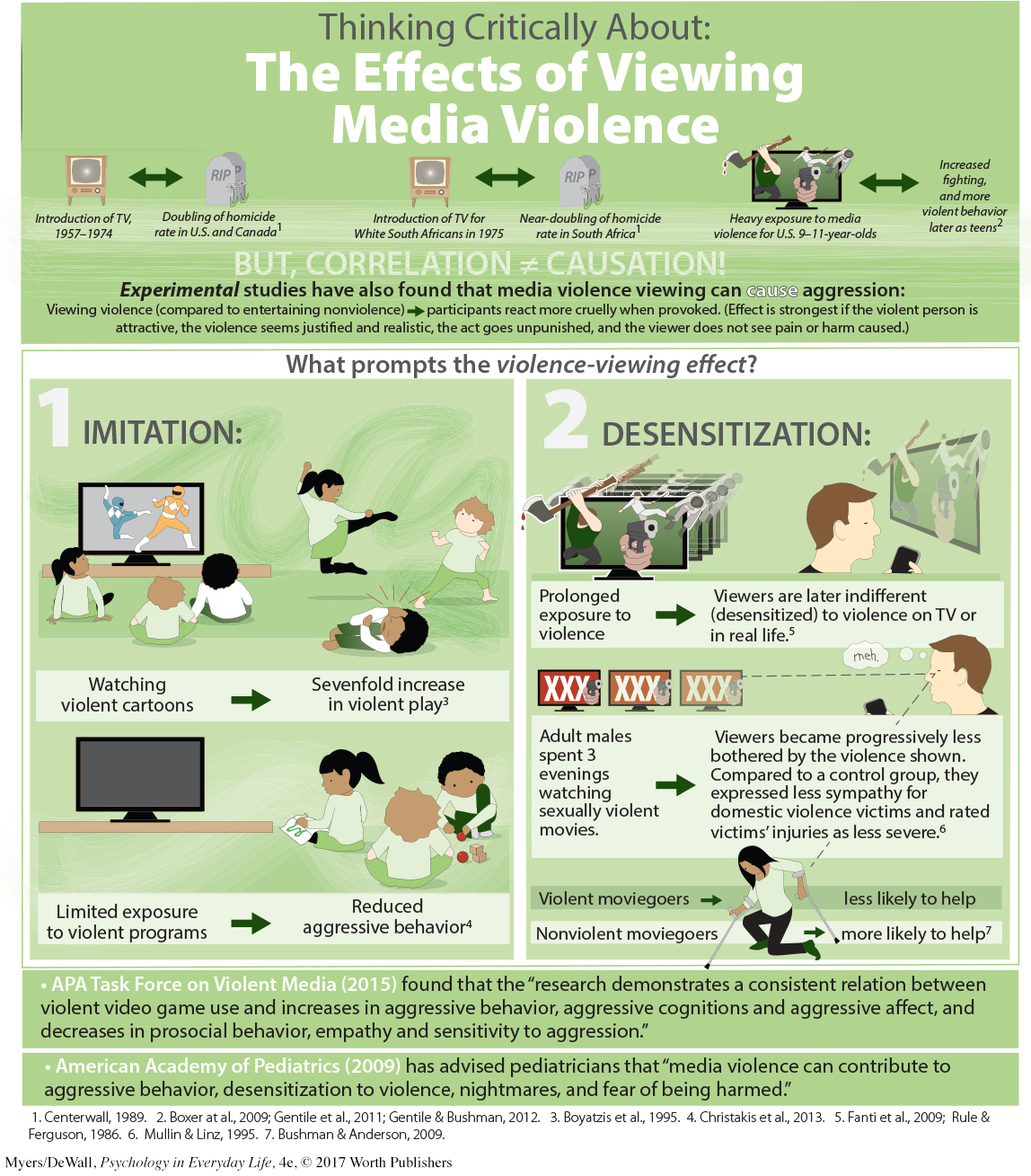

Cognition supports observational learning, in which higher animals learn without direct experience, by watching and imitating others. A child who sees his sister burn her fingers on a hot stove learns, without getting burned himself, that hot stoves can burn us. We learn our native languages and all kinds of other specific behaviors by observing and imitating others, a process called modeling.

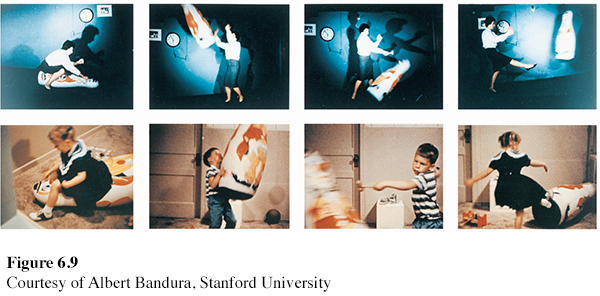

Picture this scene from an experiment by Albert Bandura, the pioneering researcher of observational learning (Bandura et al., 1961). A preschool child works on a drawing. In another part of the room, an adult builds with Tinkertoys. As the child watches, the adult gets up and for nearly 10 minutes pounds, kicks, and throws around the room a large, inflated Bobo doll, yelling, “Sock him in the nose. . . . Hit him down. . . . Kick him.”

The child is then taken to another room filled with appealing toys. Soon the experimenter returns and tells the child she has decided to save these good toys “for the other children.” She takes the now-

Compared with other children in the study, those who viewed the model’s actions were much more likely to lash out at the doll. Apparently, observing the aggressive outburst lowered their inhibitions. But something more was also at work, for the children often imitated the very acts they had observed and used the very words they had heard (FIGURE 6.9).

For 3 minutes of classic footage, see LaunchPad’s Video: Bandura’s Bobo Doll Experiment.

For 3 minutes of classic footage, see LaunchPad’s Video: Bandura’s Bobo Doll Experiment.

That “something more,” Bandura suggested, was this: By watching models, we vicariously (in our imagination) experience what they are experiencing. Through vicarious reinforcement or vicarious punishment, we learn to anticipate a behavior’s consequences in situations like those we are observing. We are especially likely to experience models’ outcomes vicariously if we identify with them—

similar to ourselves.

successful.

admirable.

Functional MRI (fMRI) scans show that when people observe someone winning a reward, their own brain reward systems become active, much as if they themselves had won the reward (Mobbs et al., 2009). Even our learned fears may extinguish as we observe another safely navigating the feared situation (Golkar et al., 2013).

Mirrors and Imitation in the Brain

In one of those quirky events that appear in the growth of science, researchers made an amazing discovery.

On a 1991 hot summer day in Parma, Italy, a lab monkey awaited its researchers’ return from lunch. The researchers had implanted a monitoring device in the monkey’s brain, in a frontal lobe region important for planning and acting out movements. The device would alert the researchers to activity in that region. When the monkey moved a peanut into its mouth, for example, the device would buzz. That day, the monkey stared as one of the researchers entered the lab carrying an ice cream cone in his hand. As the researcher raised the cone to lick it, the monkey’s monitor buzzed—

mirror neuron a neuron that fires when we perform certain actions and when we observe others performing those actions; a neural basis for imitation and observational learning.

This quirky event, the researchers believed, marked an amazing discovery: a previously unknown type of neuron (Rizzolatti et al., 2002, 2006). In their view, these mirror neurons provided a neural basis for everyday imitation and observational learning. When a monkey grasps, holds, or tears something, these neurons fire. They likewise fire when the monkey observes another doing so. When one monkey sees, these neurons mirror what another monkey does. (Other researchers continue to debate the existence and importance of mirror neurons and related brain networks [Gallese et al., 2011; Hickok, 2014].)

It’s not just monkey business. Imitation occurs in various animal species, but it is most striking in humans. Our catchphrases, fashions, ceremonies, foods, traditions, morals, and fads all spread by one person copying another. Children and even infants are natural imitators (Marshall & Meltzoff, 2014). Shortly after birth, babies may imitate adultswho stick out their tongue. By 8 to 16 months, infants imitate various novel gestures (Jones, 2007). By age 12 months, they begin looking where an adult islooking (Meltzoff et al., 2009). And by 14 months, children imitate acts modeled on TV (Meltzoff & Moore, 1997). Even as 2½-year-

Because of the brain’s responses, emotions are contagious. As we observe others’ postures, faces, voices, and writing styles, we unconsciously mimic them. And by doing that, we grasp others’ states of mind and we feel what they are feeling (Bernieri et al., 1994; Ireland & Pennebaker, 2010).

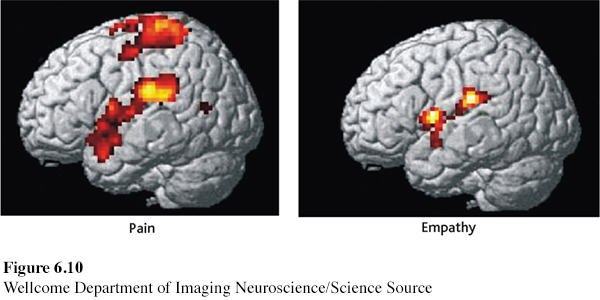

Seeing a loved one’s pain, our faces mirror the loved one’s emotion. And so do our brains. In the fMRI scan in FIGURE 6.10, the pain imagined by an empathic romantic partner triggered some of the same brain activity experienced by the loved one in actual pain (Singer et al., 2004). Even fiction reading may trigger such activity, as we indirectly experience the feelings and actions described (Mar & Oatley, 2008; Speer et al., 2009). In one experiment, university students read a fictional fellow student’s description of overcoming obstacles to vote. A week later, those who read the first-

So real are these mental instant replays that we may remember an action we have observed as an action we have actually performed (Lindner et al., 2010). The bottom line: Brain activity underlies our intensely social nature.

Applications of Observational Learning

LOQ 6-

So the big news from Bandura’s studies and the mirror-

Prosocial Effects

prosocial behavior positive, constructive, helpful behavior. The opposite of antisocial behavior.

The good news is that prosocial (positive, helpful) behavior models can have prosocial effects. One research team found that across seven countries, viewing prosocial TV, movies, and video games boosted later helping behavior (Prot et al., 2014). Real people who model nonviolent, helpful behavior can also prompt similar behavior in others. India’s Mahatma Gandhi and America’s Martin Luther King, Jr., both drew on the power of modeling, making nonviolent action a powerful force for social change in both countries (Matsumoto et al., 2015). Parents are also powerful models. European Christians who risked their lives to rescue Jews from the Nazis usually had a close relationship with at least one parent who modeled a strong moral or humanitarian concern. This was also true for U.S. civil rights activists in the 1960s (London, 1970; Oliner & Oliner, 1988).

Models are most effective when their actions and words are consistent. To encourage children to read, read to them and surround them with books and people who read. To increase the odds that your children will practice your religion, worship and attend religious activities with them. Sometimes, however, models say one thing and do another. Many parents seem to operate according to the principle “Do as I say, not as I do.” Experiments suggest that children learn to do both (Rice & Grusec, 1975; Rushton, 1975). Exposed to a hypocrite, they tend to imitate the hypocrisy—

Antisocial Effects

The bad news is that observational learning may also have antisocial effects. This helps us understand why abusive parents might have aggressive children, and why many men who beat their wives had wife-

TV shows, movies, and online videos are sources of observational learning. While watching TV and videos, children may “learn” that bullying is an effective way to control others, that free and easy sex brings pleasure without later misery or disease, or that men should be tough and women gentle. And they have ample time to learn such lessons. During their first 18 years, most children in developed countries spend more time watching TV shows than they spend in school. In the United States, the average teen watches TV shows more than 4 hours a day; the average adult, 3 hours (Robinson & Martin, 2009; Strasburger et al., 2010).

Viewers are learning about life from a rather peculiar storyteller, one with a taste for violence. During one closely studied year, nearly 6 in 10 U.S. network and cable programs featured violence. Of those violent acts, 74 percent went unpunished, and the victims’ pain was usually not shown. Nearly half the events were portrayed as “justified,” and nearly half the attackers were attractive (Donnerstein, 1998). These conditions define the recipe for the violence-

In 2012, a well-

Screen time’s greatest effect may stem from what it displaces. Children and adults who spend several hours a day in front of a screen spend that many fewer hours in other pursuits—

Retrieve + Remember

Question 6.16

•Jason’s parents and older friends all smoke, but they advise him not to. Juan’s parents and friends don’t smoke, but they say nothing to deter him from doing so. Will Jason or Juan be more likely to start smoking?

ANSWER: Jason may be more likely to smoke, because observational learning studies suggest that children tend to do as others do and say what they say.

Question 6.17

•Match the learning examples (items 1–

Classical conditioning

Operant conditioning

Latent learning

Observational learning

Biological predispositions

Knowing the way from your bed to the bathroom in the dark

Speaking the language your parents speak

Salivating when you smell brownies in the oven

Disliking the taste of chili after becoming violently sick a few hours after eating chili

Your dog racing to greet you on your arrival home

ANSWERS: 1. c (You’ve probably learned your way by latent learning.) 2. d (Observational learning may have contributed to your imitating the language modeled by your parents.) 3. a (Through classical conditioning you have associated the smell with the anticipated tasty result.) 4. e (You are biologically predisposed to develop a conditioned taste aversion to foods associated with illness.) 5. b (Through operant conditioning your dog may have come to associate approaching excitedly with attention, petting, and a treat.)

LOQ 6-