7.1 Studying Memory

LOQ LearningObjectiveQuestion

7-

Memory the persistence of learning over time through the encoding, storage, and retrieval of information.

Be thankful for memory—your storehouse of accumulated learning. Your memory enables you to recognize family, speak your language, find your way home, and locate food and water. Your memory allows you to enjoy an experience and then mentally replay it and enjoy it again. Without memory, you could not savor past achievements, nor feel guilt or anger over painful past events. You would instead live in an endless present, each moment fresh. Each person would be a stranger, every language foreign, every task—

Earlier, in the Sensation and Perception chapter, we considered one of psychology’s big questions: How does the world out there enter your brain? In this chapter we consider a related question: How does your brain pluck information out of the world around you and store it for a lifetime of use? Said simply, how does your brain construct your memories?

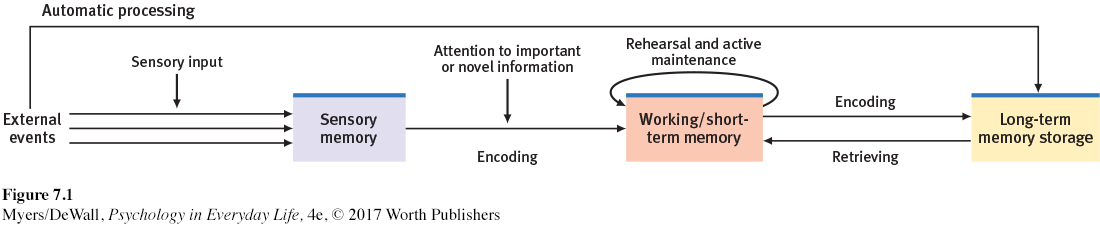

To help clients imagine future buildings, architects create miniature models. Similarly, psychologists create models of memory to help us think about how our brain forms and retrieves memories. An information-

Encoding the process of getting information into the memory system.

get information into our brain, a process called encoding.

Storage the process of retaining encoded information over time.

retain that information, a process called storage.

Retrieval the process of getting information out of memory storage.

later get the information back out, a process called retrieval.

Let’s take a closer look.

An Information-Processing Model

LOQ 7-

Richard Atkinson and Richard Shiffrin (1968) proposed that we form memories in three stages.

sensory memory the immediate, very brief recording of sensory information in the memory system.

We first record to-

be- remembered information as a fleeting sensory memory. short-

term memory activated memory that holds a few items briefly (such as the seven digits of a phone number while calling) before the information is stored or forgotten.From there, we process information into short-

term memory , where we encode it through rehearsal.long-

term memory the relatively permanent and limitless storehouse of the memory system. Includes knowledge, skills, and experiences.Finally, information moves into long-

term memory for later retrieval.

Other psychologists later updated this model with important newer concepts, including working memory and automatic processing (FIGURE 7.1).

Working Memory

working memory a newer understanding of short-

So much active processing takes place in the middle stage that psychologists now prefer the term working memory. In Atkinson and Shiffrin’s original model, the second stage appeared to be a temporary shelf for holding recent thoughts and experiences. We now know that this working-

For most of you, what you are reading enters your working memory through vision. You may also silently repeat the information using auditory rehearsal. Integrating these memory inputs with your existing long-

For a 14-

For a 14-

Without focused attention, information often fades. If you think you can look something up later, you attend to it less and forget it more quickly. In one experiment, people read and typed new information they would later need, such as “An ostrich’s eye is bigger than its brain.” If they knew the information would be available online, they invested less energy in remembering it, and they remembered it less well (Sparrow et al., 2011; Wegner & Ward, 2013). Online, out of mind.

Retrieve + Remember

Question 7.1

•How does the working memory concept update the classic Atkinson-

ANSWER: The newer idea of a working memory emphasizes the active processing that we now know takes place in Atkinson-

Question 7.2

•What are two basic functions of working memory?

ANSWER: (1) Active processing of incoming visual and auditory information, and (2) focusing our spotlight of attention.