7.5 Forgetting

LOQ 7-

If a memory-

More often, however, our quirky memories fail us when we least expect it. My [DM’s] own memory can easily call up such episodes as that wonderful first kiss with the woman I love, or trivial facts like the air mileage from London to Detroit. Then it abandons me when I discover that I have failed to encode, store, or retrieve a student’s name or the spot where I left my sunglasses.

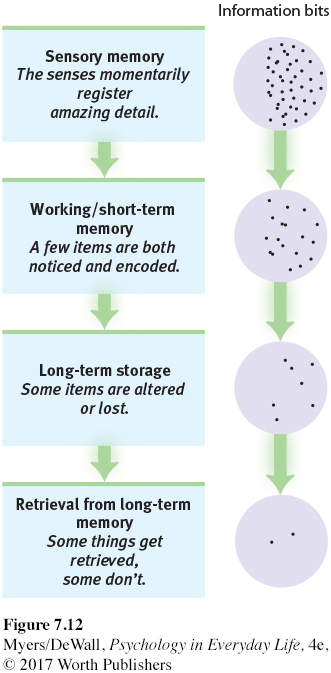

As we process information, we sift, change, or lose most of it (FIGURE 7.12).

Forgetting and the Two-Track Mind

For some, memory loss is severe and permanent, as it was for Henry Molaison (H. M.), whom you met earlier in this chapter. Molaison could recall his past, but he could not form new conscious memories. Neurologist Oliver Sacks (1933–

Jimmie turned pale, gripped the chair, cursed, then became frantic: “What’s going on? What’s happened to me? Is this a nightmare? Am I crazy? Is this a joke?” When his attention was directed to some children playing baseball, his panic ended, the dreadful mirror forgotten.

Sacks showed Jimmie a photo from National Geographic. “What is this?” he asked.

“It’s the Moon,” Jimmie replied.

“No, it’s not,” Sacks answered. “It’s a picture of the Earth taken from the Moon.”

“Doc, you’re kidding! Someone would’ve had to get a camera up there!”

“Naturally.”

“Hell! You’re joking—

Amnesia literally “without memory”—a loss of memory, often due to brain trauma, injury, or disease.

Careful testing of these unique people reveals something even stranger. Although they cannot recall new facts or anything they have done recently, they can learn new skills and can be classically conditioned. Shown hard-

For a 6-

For a 6-

Molaison and Jimmie lost their ability to form new explicit memories, but their automatic processing ability remained intact. They could learn how to do something, but they had no conscious recall of learning their new skill. Such sad cases confirm that we have two distinct memory systems, controlled by different parts of the brain.

For most of us, forgetting is a less drastic process. Let’s consider some of the reasons we forget.

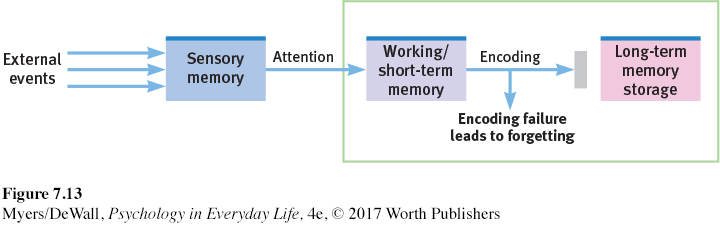

Encoding Failure

Much of what we sense we never notice, and what we fail to encode, we will never remember (FIGURE 7.13). Age can affect encoding ability. When young adults encode new information, areas of their brain jump into action. In older adults, these areas are slower to respond. Learning and retaining a new neighbor’s name or mastering a new smart phone becomes more of a challenge. This encoding lag helps explain age-

But no matter how young we are, we pay conscious attention to only a limited portion of the vast number of sights and sounds bombarding us. Consider: You have surely seen the Apple logo thousands of times. Can you draw it? In one study, only 1 of 85 UCLA students (including 52 Apple users) could do so accurately (Blake et al., 2015). Without encoding effort, many might-

Storage Decay

Even after encoding something well, we may later forget it. That master of nonsense-

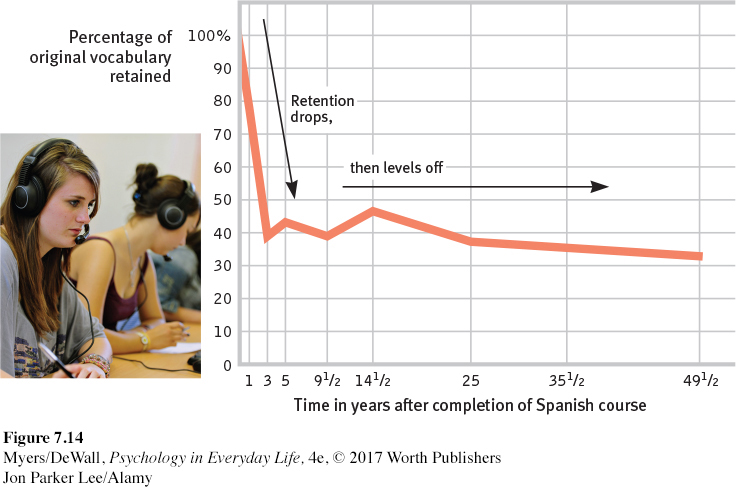

People studying Spanish as a foreign language showed this forgetting curve for Spanish vocabulary (Bahrick, 1984). Compared with others who had just completed a high school or college Spanish course, people 3 years out of school had forgotten much of what they had learned. However, what they remembered then, they still remembered 25 and more years later. Their forgetting had leveled off (FIGURE 7.14).

memory trace lasting physical change in the brain as a memory forms.

One explanation for these forgetting curves is a gradual fading of the physical memory trace, which is a physical change in the brain as a memory forms. Researchers are getting closer to solving the mystery of the physical storage and decay of memories. But memories fade for many reasons, including other learning that disrupts our retrieval.

Retrieval Failure

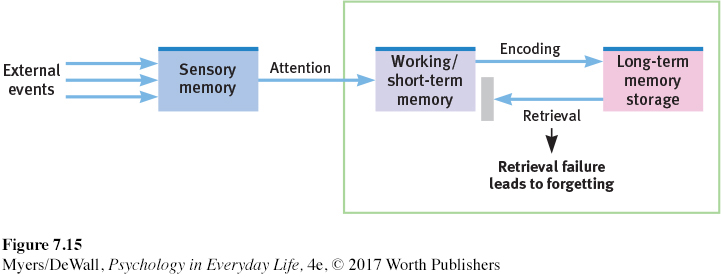

We can compare forgotten events to books you can’t find in your local library. Some aren’t available because they were never acquired (not encoded). Others have been discarded (stored memories decay).

But there is a third possibility. The book—

Here’s a question to test your memory. Do you recall the second sentence we asked you to remember—

Retrieval problems occasionally stem from interference and even from motivated forgetting.

Interference

proactive interference the forward-

As you collect more and more information, your mental attic never fills, but it gets cluttered. Sometimes the clutter interferes, as new and old learning bump into each other and compete for your attention. Proactive (forward-

retroactive interference the backward-

Retroactive (backward-

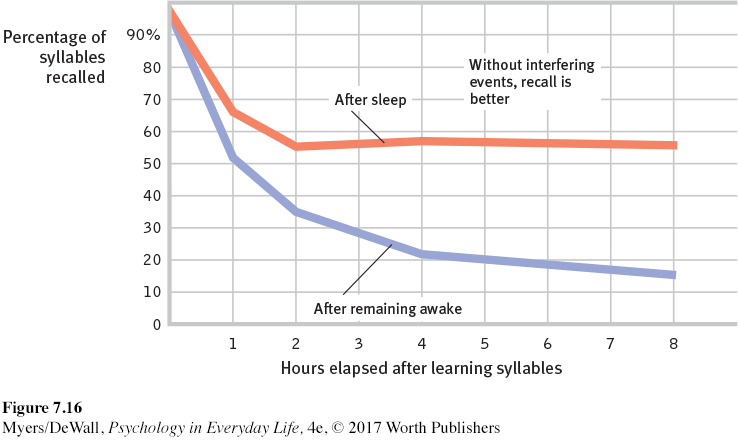

New learning in the hour before we fall asleep suffers less retroactive interference because the chances of disruption are few (Diekelmann & Born, 2010; Nesca & Koulack, 1994). Researchers first discovered this in a now-

To experience a demonstration and explanation of interference effects on memory, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Forgetting.

To experience a demonstration and explanation of interference effects on memory, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Forgetting.

The hour before sleep is a good time to commit information to memory (Scullin & McDaniel, 2010), but not the seconds just before sleep (Wyatt & Bootzin, 1994). And if you’re considering learning while sleeping, forget it. We have little memory for information played aloud in the room during sleep, although our ears do register it (Wood et al., 1992).

Old and new information do not always compete, of course. Knowing Latin may actually help us to learn French. This effect is called positive transfer.

Motivated Forgetting

To remember our past is often to revise it. Years ago, the huge cookie jar in my [DM’s] kitchen was jammed with freshly baked cookies. Still more were cooling across racks on the counter. A day later, not a crumb was left. Who had taken them? During that time, my wife, three children, and I were the only people in the house. So while memories were still fresh, I conducted a little memory test. Andy admitted wolfing down as many as 20. Peter thought he had eaten 15. Laura guessed she had stuffed her then-

Why were our estimates so far off? Was our cookie confusion an encoding problem? (Did we just not notice what we had eaten?) Was it a storage problem? (Might our memories of cookies, like Ebbinghaus’ memory of nonsense syllables, have melted away almost as fast as the cookies themselves?) Or was the information still intact but not retrievable because it would be embarrassing to remember?

repression in psychoanalytic theory, the basic defense mechanism that banishes from consciousness the thoughts, feelings, and memories that arouse anxiety.

Sigmund Freud might have argued that our memory systems self-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 7.15

•What are three ways we forget, and how does each of these happen?

ANSWER: (1) Encoding failure: Unattended information never entered our memory system. (2) Storage decay: Information fades from our memory. (3) Retrieval failure: We cannot access stored information accurately, sometimes due to interference or motivated forgetting.

Question 7.16

•You will experience less _______ (proactive/retroactive) interference if you learn new material in the hour before sleep than you will if you learn it before turning to another subject.

ANSWER: retroactive

Question 7.17

•Freud believed that we _______ unacceptable memories to minimize anxiety.

ANSWER: repress