8.1 Thinking

Concepts

LOQ LearningObjectiveQuestion

8-

cognition all the mental activities associated with thinking, knowing, remembering, and communicating.

concept a mental grouping of similar objects, events, ideas, or people.

Psychologists who study cognition focus on the mental activities associated with thinking, knowing, remembering, and communicating information. One of these activities is forming concepts—mental groupings of similar objects, events, ideas, or people. The concept chair includes many items—

Concepts simplify our thinking. Imagine life without them. We could not ask a child to “throw the ball” because there would be no concept of throw or ball. We could not say “They were angry.” We would have to describe expressions and words. Concepts such as ball and anger give us much information with little mental effort.

prototype a mental image or best example of a category. Matching new items to a prototype provides a quick and easy method for sorting items into categories (as when you compare a feathered creature to a prototypical bird, such as a robin).

We often form our concepts by developing a prototype—a mental image or best example of a category (Rosch, 1978). People more quickly agree that “a robin is a bird” than that “a penguin is a bird.” For most of us, the robin is the “birdier” bird; it more closely resembles our bird prototype. When something closely matches our prototype of a concept, we readily recognize it as an example of the concept.

Sometimes, though, our experiences don’t match up neatly with our prototypes. When this happens, our category boundaries may blur. Is a 17-

Similarly, when symptoms don’t fit one of our disease prototypes, we are slow to perceive an illness (Bishop, 1991). People whose heart attack symptoms (shortness of breath, exhaustion, a dull weight in the chest) don’t match their heart attack prototype (sharp chest pain) may not seek help. Concepts speed and guide our thinking. But they don’t always make us wise.

Solving Problems

LOQ 8-

One tribute to our rationality is our impressive problem-

algorithm a methodical, logical rule or procedure that guarantees you will solve a particular problem. Contrasts with the usually speedier—

heuristic a simple thinking strategy that often allows you to make judgments and solve problems efficiently; usually speedier but also more error-

Some problems we solve through trial and error. Thomas Edison tried thousands of light bulb filaments before stumbling upon one that worked. For other problems, we use algorithms, step-

insight a sudden realization of the solution to a problem; contrasts with strategy-

Sometimes we puzzle over a problem, with no feeling of getting closer to the answer. Then, suddenly the pieces fall together in a flash of insight—an abrupt, true-

Bursts of brain activity accompany sudden flashes of insight (Kounios & Beeman, 2009; Sandkühler & Bhattacharya, 2008). In one study, researchers asked people to think of a word that forms a compound word or phrase with each of three words in a set (such as pine, crab, and sauce). When people knew the answer, they were to press a button, which would sound a bell. (Need a hint? The word is a fruit.2) About half the solutions arrived by a sudden Aha! insight. Before the Aha! moment, the problem solvers’ frontal lobes (which are involved in focusing attention) were active. Then, at the instant of discovery, there was a burst of activity in their right temporal lobe, just above the ear (FIGURE 8.1).

Insight gives us a happy sense of satisfaction. The joy of a joke is similarly a sudden “I get it!” reaction to a double meaning or a surprise ending: “You don’t need a parachute to skydive. You only need a parachute to skydive twice.” Comedian Groucho Marx was a master at this: “I once shot an elephant in my pajamas. How he got into my pajamas I’ll never know.”

confirmation bias a tendency to search for information that supports your preconceptions and to ignore or distort evidence that contradicts them.

Insightful as we are, other cognitive tendencies may lead us astray. Confirmation bias is our tendency to seek evidence for our ideas more eagerly than we seek evidence against them (Klayman & Ha, 1987; Skov & Sherman, 1986). Peter Wason (1960) demonstrated confirmation bias in a now-

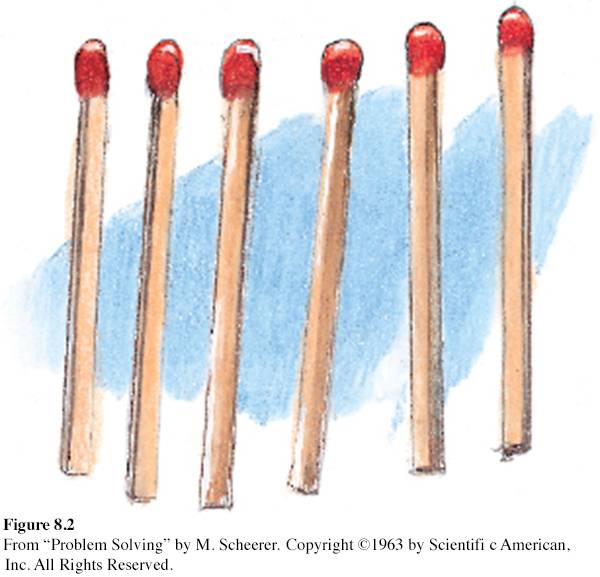

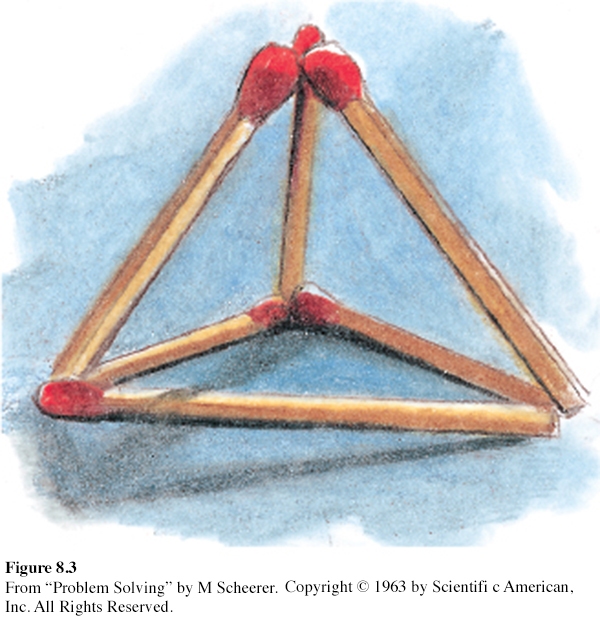

fixation in thinking, the inability to see a problem from a new perspective; an obstacle to problem solving.

In real life, this tendency can have grave results. Having formed a belief—

Making Good (and Bad) Decisions and Judgments

LOQ 8-

intuition an effortless, immediate, automatic feeling or thought, as contrasted with explicit, conscious reasoning.

Each day we make hundreds of judgments and decisions. (Should I take a jacket? Can I trust this person? Should I shoot the basketball or pass to the player who’s hot?) As we judge the odds and make our decisions, we seldom take the time and effort to reason systematically. We just follow our intuition, our fast, automatic, unreasoned feelings and thoughts. After interviewing leaders in government, business, and education, one social psychologist concluded that they often made decisions without considered thought and reflection. How did they usually reach their decisions? “If you ask, they are likely to tell you . . . they do it mostly by the seat of their pants” ( Janis, 1986).

Quick-Thinking Heuristics

availability heuristic judging the likelihood of an event based on its availability in memory; if an event comes readily to mind (perhaps because it was vivid), we assume it must be common.

When we need to make snap judgments, the mental shortcuts we call heuristics enable quick thinking without conscious awareness. As cognitive psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman (1974) showed, these automatic, intuitive strategies, although generally helpful, can sometimes lead even the smartest people into quick but dumb decisions.3 Consider the availability heuristic, which operates when we estimate how common an event is, based on its mental availability. Anything that makes information “pop” into mind—

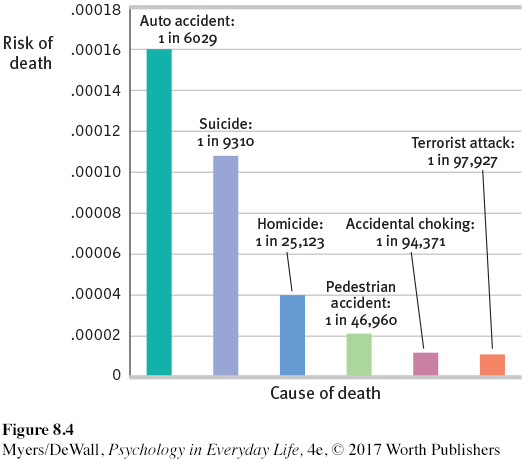

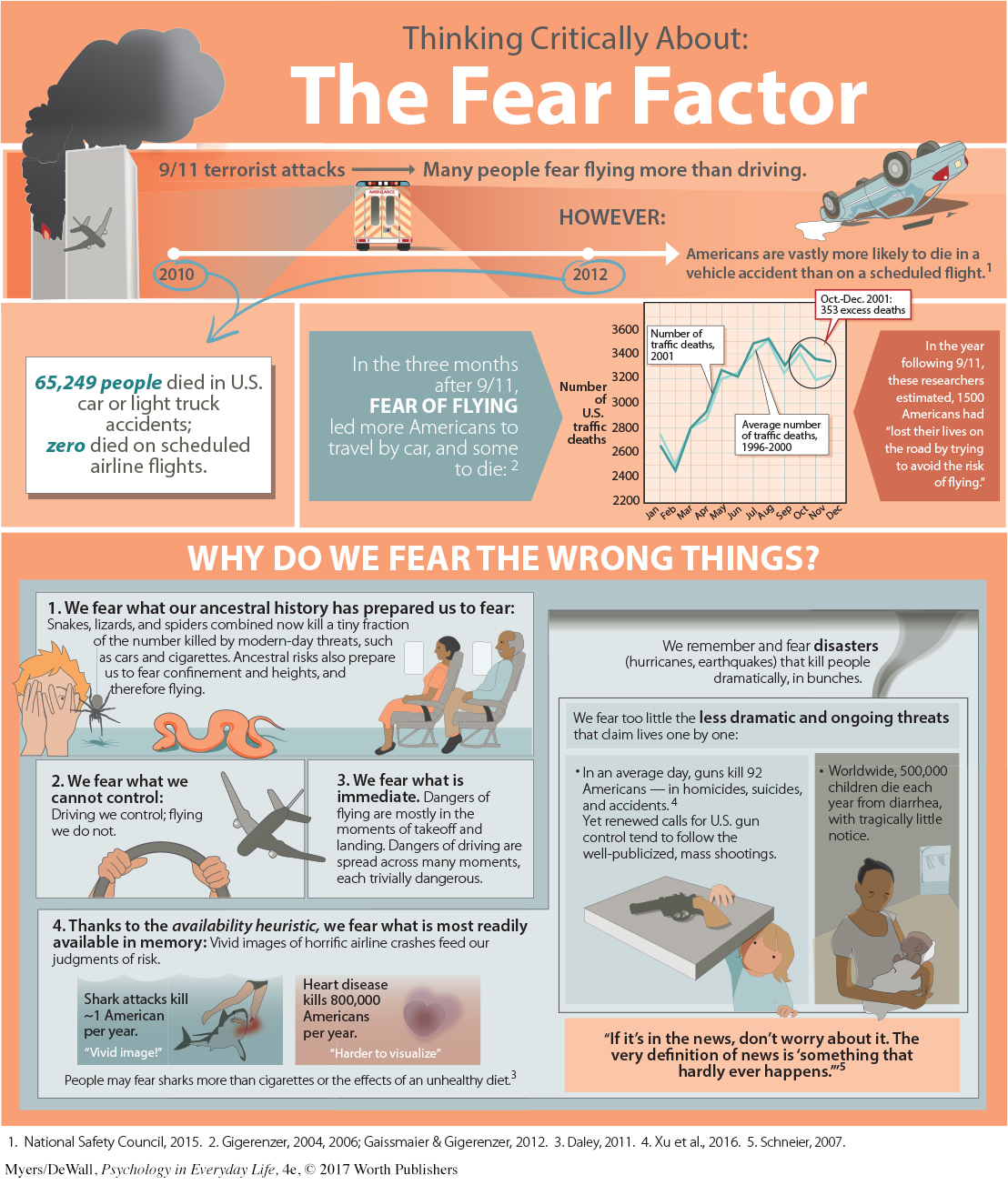

The availability heuristic can distort our judgments of other people. If people from a particular ethnic or religious group commit a terrorist act, as happened on September 11, 2001, our readily available memory of the dramatic event may shape our impression of the whole group. Even during that horrific year, terrorist acts claimed comparatively few lives. Despite the much greater risk of death from other causes (FIGURE 8.4), the vivid image of 9/11 terror came more easily to mind. Emotion-

Over 40 nations have sought to harness the positive power of vivid, memorable images by putting eye-

LOQ 8-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 8.1

•Why can news be described as “something that hardly ever happens”? How does knowing this help us assess our fears?

ANSWER: If a tragic event such as a plane crash makes the news, it grabs our attention more than the much more common bad events, such as traffic accidents. Knowing this, we can worry less about unlikely events and think more about improving the safety of our everyday activities. (For example, we can wear a seat belt when in a vehicle and use the crosswalk when walking.)

Overconfidence: Was There Ever Any Doubt?

LOQ 8-

overconfidence the tendency to be more confident than correct—

Sometimes our decisions and judgments go awry because we are more confident than correct. When answering factual questions such as “Is absinthe a liqueur or a precious stone?” only 60 percent of people in one study answered correctly. (It’s a licorice-

Classrooms are full of overconfident students who expect to finish assignments and write papers ahead of schedule (Buehler et al., 1994, 2002). In fact, such projects generally take about twice the number of days predicted. We also are overconfident about our future free time (Zauberman & Lynch, 2005). Surely we’ll have more free time next month than we do today. So we happily accept invitations, only to discover we’re just as busy when the day rolls around. And believing we’ll surely have more money next year, we take out loans or buy on credit. Despite our past overconfident predictions, we remain overly confident of our next one.

Overconfidence affects us at the group level, too. History is full of leaders who, when waging war, were more confident than correct. In politics, overconfidence feeds extreme political views. Sometimes the less we know, the more definite we sound.

Nevertheless, overconfidence can have adaptive value. Believing that their decisions are right and they have time to spare, self-

Our Beliefs Live On—Sometimes Despite Evidence

belief perseverance clinging to beliefs even after evidence has proven them wrong.

Our overconfidence is startling. Equally startling is belief perseverance—our tendency to cling to our beliefs even when the evidence proves us wrong. Consider a classic study of people with opposing views of the death penalty (Lord et al., 1979). Both sides were asked to read the same material—

So how can smart thinkers avoid belief perseverance? A simple remedy is to consider the opposite. In a repeat of the death penalty study, researchers asked some participants to be “as objective and unbiased as possible” (Lord et al., 1984). This plea did nothing to reduce people’s biases. They also asked another group to consider “whether you would have made the same high or low evaluations had exactly the same study produced results on the other side of the issue.” In this group, people’s views did change. After imagining the opposite findings, they judged the evidence in a much less biased way.

The more we come to appreciate why our beliefs might be true, the more tightly we cling to them. Once we have explained to ourselves why candidate X or Y will be a better commander-

Framing: Let’s Put It This Way . . .

framing the way an issue is posed; framing can significantly affect decisions and judgments.

Framing—the way we present an issue—

Choosing to live or die. Imagine two surgeons explaining the risk of an upcoming surgery. One explains that during this type of surgery, 10 percent of patients die. The other explains that 90 percent survive. The information is the same. The effect is not. In real-

life surveys, patients and physicians overwhelmingly say the risk seems greater when they hear that 10 percent die (Marteau, 1989; McNeil et al., 1988; Rothman & Salovey, 1997). Choosing to be an organ donor. In many European countries, as well as in the United States, people renewing their driver’s license can decide whether to be organ donors. In some countries, the assumed answer is Yes, unless you opt out. Nearly 100 percent of the people in these opt-

out countries agree to be donors. In countries where the assumed answer is No, fewer than half have agreed to be donors (Hajhosseini et al., 2013; Johnson & Goldstein, 2003). Making students happier. One economist’s students were upset by a “hard” exam, on which the class average was 72 out of 100. So on the next exam, he made the highest possible score 137 points. Although the class average score of 96 was only 70 percent correct, “the students were delighted.” (The number 96 felt so much better than 72.) So he continued the reframed exam results thereafter (Thaler, 2015).

The point to remember: Framing can influence our decisions.

The Perils and Powers of Intuition

LOQ 8-

We have seen how our unreasoned thinking can plague our efforts to solve problems, assess risks, and make wise decisions. Moreover, these perils of intuition persist even when people are offered extra pay for thinking smart or when asked to justify their answers. And they persist even among those with high intelligence, including expert physicians, clinicians, and U.S. federal intelligence agents (Reyna et al., 2013; Shafir & LeBoeuf, 2002; Stanovich & West, 2008).

But psychological science is also revealing intuition’s powers:

Intuition is analysis “frozen into habit” (Simon, 2001). It is implicit (unconscious) knowledge—

what we’ve learned and recorded in our brains but can’t fully explain (Chassy & Gobet, 2011; Gore & Sadler- Smith, 2011). We see this ability to size up a situation and react in an eyeblink in chess masters playing speed chess, when they intuitively know the right move (Burns, 2004). We see it in the smart and quick judgments of seasoned nurses, firefighters, art critics, and car mechanics. We see it in skilled athletes who react without thinking. Indeed, conscious thinking may disrupt well- practiced movements, leading skilled athletes to choke under pressure, as when shooting free throws (Beilock, 2010). And we would see this instant intuition in you, too, for anything in which you have developed a deep and special knowledge, based on experience.  HMM . . . MALE OR FEMALE? When acquired expertise becomes an automatic habit, as it is for experienced chicken sexers, it feels like intuition. At a glance, they just know, yet cannot easily tell you how they know.Jean Philippe Ksiazek/AFP/Getty

HMM . . . MALE OR FEMALE? When acquired expertise becomes an automatic habit, as it is for experienced chicken sexers, it feels like intuition. At a glance, they just know, yet cannot easily tell you how they know.Jean Philippe Ksiazek/AFP/GettyIntuition is usually adaptive. Our fast and frugal heuristics let us intuitively assume that fuzzy-

looking objects are far away— which they usually are, except on foggy mornings. Our learned associations surface as gut feelings, right or wrong: Seeing a stranger who looks like someone who has harmed or threatened us in the past, we may automatically react with distrust. Newlyweds’ implicit attitudes to their new spouses likewise predict their future marital happiness (McNulty et al., 2013). Page 228Intuition is huge. Unconscious automatic influences are constantly affecting our judgments (Custers & Aarts, 2010). Imagine participating in this decision-

making experiment (Strick et al., 2010). You’ve been assigned to one of three groups that will receive complex information about four apartment options. Members of the first group will state their choice immediately after reading the information. Those in the second group will analyze the information before choosing one of the options. Your group, the third, will consider the information but then be distracted for a time before giving your decision. Which group will make the smartest decision?

Did you guess the second group would make the best choice? Most people do, believing that the more complex the choice, the smarter it is to make decisions rationally rather than intuitively (Inbar et al., 2010). Actually, the third group made the best choice in this real-

Critics remind us, however, that with most complex tasks, deliberate, conscious thought helps (Lassiter et al., 2009; Newell, 2015; Nieuwenstein et al., 2015; Payne et al., 2008). With many sorts of problems, smart thinkers may initially fall prey to an intuitive option but then reason their way to a better answer. Consider a random coin flip. If someone flipped a coin six times, which of the following sequences of heads (H) and tails (T) would seem most likely: HHHTTT or HTTHTH or HHHHHH?

Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky (1972) reported that most people believe HTTHTH would be the most likely random sequence. (Ask someone to predict six coin tosses and they will likely tell you a sequence like this.) Actually, each of these exact sequences is equally likely (or, you might say, equally unlikely).

The bottom line: Our two-

Thinking Creatively

LOQ 8-

creativity the ability to produce new and valuable ideas.

Creativity is the ability to produce ideas that are both novel and valuable (Hennessey & Amabile, 2010). Consider Princeton mathematician Andrew Wiles’ incredible, creative moment. Pierre de Fermat (1601–

Wiles had searched for the answer for more than 30 years and reached the brink of a solution. One morning in 1994, out of the blue, an “incredible revelation” struck him. “It was so . . . beautiful . . . so simple and so elegant. I couldn’t understand how I’d missed it. . . . It was the most important moment of my working life” (Singh, 1997, p. 25).

convergent thinking narrowing the available solutions to determine the single best solution to a problem.

divergent thinking expanding the number of possible solutions to a problem; creative thinking that branches out in different directions.

Creativity like Wiles’ requires a certain level of aptitude (ability to learn). But creativity is more than school smarts, and it requires a different kind of thinking. Aptitude tests (such as the SAT) typically require convergent thinking—an ability to provide a single correct answer. Creativity tests (How many uses can you think of for a brick?) require divergent thinking—the ability to consider many different options and to think in novel ways.

Robert Sternberg and his colleagues (1988, 2003; Sternberg & Lubart, 1991, 1992) believe creativity has five ingredients.

Expertise—

a solid knowledge base— furnishes the ideas, images, and phrases we use as mental building blocks. The more blocks we have, the more novel ways we can combine them. Wiles’ well- developed base of mathematical knowledge gave him access to many combinations of ideas and methods. Imaginative thinking skills give us the ability to see things in novel ways, to recognize patterns, and to make connections. Wiles’ imaginative solution combined two partial solutions.

A venturesome personality seeks new experiences, tolerates gray areas, takes risks, and stays focused despite obstacles. Wiles said he worked in near-

isolation from the mathematics community, partly to stay focused and avoid distraction. This kind of focus and dedication is an enduring trait. Intrinsic motivation (as explained in Chapter 6) arises internally rather than from external rewards or pressures (extrinsic motivation) (Amabile & Hennessey, 1992). Creative people seem driven by the pleasure and challenge of the work itself, not by meeting deadlines, impressing people, or making money. As Wiles said, “I was so obsessed by this problem that . . . I was thinking about it all the time—

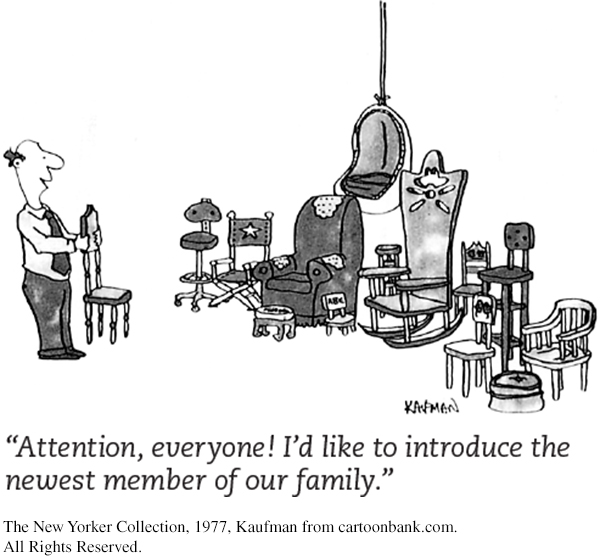

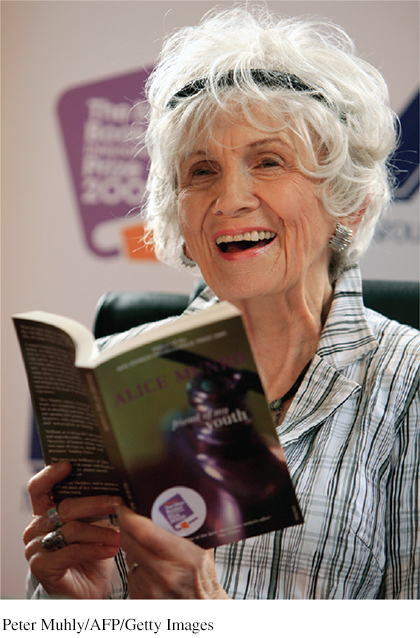

[from] when I woke up in the morning to when I went to sleep at night” (Singh & Riber, 1997).  IMAGINATIVE THINKING Cartoonists often display creativity as they see things in new ways or make unusual connections.Dave Coverly/Speed BumpThe New Yorker Collection, 2006, Christopher Weyant, from cartoonbank.com. All Rights Reserved.

IMAGINATIVE THINKING Cartoonists often display creativity as they see things in new ways or make unusual connections.Dave Coverly/Speed BumpThe New Yorker Collection, 2006, Christopher Weyant, from cartoonbank.com. All Rights Reserved.A creative environment sparks, supports, and refines creative ideas. Colleagues are an important part of creative environments. In one study of 2026 leading scientists and inventors, the best known of them had challenging and supportive relationships with colleagues (Simonton, 1992). Many creative environments also minimize stress and foster focused awareness (Byron & Khazanchi, 2011). While on a retreat in a monastery, Jonas Salk solved a problem that led to the polio vaccine. Later, when he designed the Salk Institute, he provided quiet spaces where scientists could think and work without interruption (Sternberg, 2006).

Would you like some research-

Develop your expertise. What do you care about most? What do you enjoy doing? Follow your passion by broadening your knowledge base and becoming an expert at your special interest. The more you know, the more building blocks you’ll have to combine in new and creative ways.

Allow time for ideas to hatch. Think hard on a problem, but then set it aside and come back to it later. During periods of inattention (“sleeping on a problem”), automatic processing can help associations to form (Zhong et al., 2008).

Set aside time for your mind to roam freely. Creativity springs from “defocused attention” (Simonton, 2012a, b).So detach from attention-

grabbing television, social networking, and video gaming. Jog, go for a long walk, or meditate. Serenity seeds spontaneity. Experience other cultures and ways of thinking. Viewing life from a different perspective sets the creative juices flowing. Students who spend time in another country and embrace their host culture are more adept at working out creative solutions to problems (Lee et al., 2012; Tadmor et al., 2012). Even getting out of your neighborhood and exposing yourself to multicultural experiences fosters flexible thinking. Although immigrants face many challenges, developing a sense of being different from others can inspire creativity (Kim et al., 2013; Ritter et al., 2012).

* * *

TABLE 8.1 summarizes the cognitive processes and strategies discussed in this section.

| Process or Strategy | Description | Powers | Perils |

|---|---|---|---|

| Algorithm | Methodical rule or procedure | Guarantees solution | Requires time and effort |

| Heuristic | Simple thinking shortcut, such as the availability heuristic (which estimates likelihood based on how easily events come to mind) | Lets us act quickly and efficiently | Puts us at risk for errors |

| Insight | Sudden Aha! reaction | Provides instant realization of solution | May not happen |

| Confirmation bias | Tendency to search for support for our own views and ignore contradictory evidence | Lets us quickly recognize supporting evidence | Hinders recognition of contradictory evidence |

| Fixation | Inability to view problems from a new angle | Focuses thinking | Hinders creative problem solving |

| Intuition | Fast, automatic feelings and thoughts | Is based on our experience; huge and adaptive | Can lead us to overfeel and underthink |

| Overconfidence | Overestimating the accuracy of our beliefs and judgments | Allows us to be happy and to make decisions easily | Puts us at risk for errors |

| Belief perseverance | Ignoring evidence that proves our beliefs are wrong | Supports our enduring beliefs | Closes our mind to new ideas |

| Framing | Wording a question or statement so that it evokes a desired response | Can influence others’ decisions | Can produce a misleading result |

| Creativity | Ability to produce novel and valuable ideas | Produces new products | May distract from structured, routine work |

Retrieve + Remember

Question 8.2

•Match the process or strategy listed below (1–

Algorithm

Intuition

Insight

Heuristic

Fixation

Confirmation bias

Overconfidence

Creativity

Framing

Belief perseverance

Inability to view problems from a new angle; focuses thinking but hinders creative problem solving.

Step-

by- step rule or procedure that guarantees the solution but requires time and effort. Your fast, automatic, effortless feelings and thoughts based on your experience; adaptive but can lead you to overfeel and underthink.

Simple thinking shortcut that lets you act quickly and efficiently but puts you at risk for errors.

Sudden Aha! reaction that instantly reveals the solution.

Tendency to search for support for your own views and to ignore evidence that opposes them.

Holding on to your beliefs even after they are proven wrong; closing your mind to new ideas.

Overestimating the accuracy of your beliefs and judgments; allows you to be happier and to make decisions easily, but puts you at risk for errors.

Wording a question or statement so that it produces a desired response; can mislead people and influence their decisions.

The ability to produce novel and valuable ideas.

ANSWERS: 1. b, 2. c, 3. e, 4. d, 5. a, 6. f, 7. h, 8. j, 9. i, 10. g

Do Other Species Share Our Cognitive Skills?

LOQ 8-

Other species are smarter than many humans realize. Neuroscientists have agreed that “nonhuman animals, including all mammals and birds” possess the neural networks “that generate consciousness” (Low, 2012). Consider, then, what animal brains can do.

USING CONCEPTS AND NUMBERS Black bears have learned to sort pictures into animal and nonanimal categories, or concepts (Vonk et al., 2012). The great apes—

Until his death in 2007, Alex, an African Grey parrot, displayed jaw-

DISPLAYING INSIGHT We are not the only creatures to display insight. Psychologist Wolfgang Köhler (1925) placed a piece of fruit and a long stick outside the cage of a chimpanzee named Sultan, beyond his reach. Inside the cage, he placed a short stick, which Sultan grabbed, using it to try to reach the fruit. After several failed attempts, the chimpanzee dropped the stick and seemed to survey the situation. Then suddenly (as if thinking “Aha!”), Sultan jumped up and seized the short stick again. This time, he used it to pull in the longer stick, which he then used to reach the fruit.

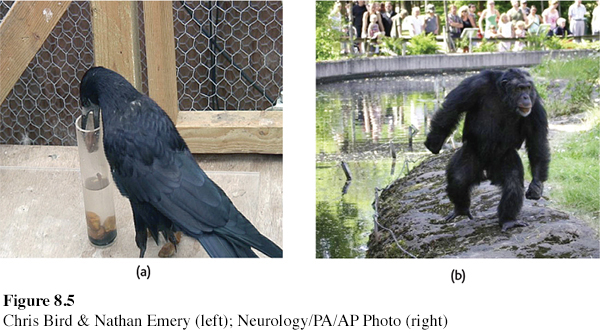

Birds, too, have displayed insight. One experiment brought to life one of Aesop’s fables (ancient Greek stories), in which a thirsty crow is unable to reach the water in a partly filled pitcher. See the crow’s solution (exactly as in the fable) in FIGURE 8.5.

USING TOOLS AND TRANSMITTING CULTURE Like humans, other animals invent behaviors and transmit cultural patterns to their observing peers and offspring (Boesch-

Chimpanzees have shown altruism, cooperation, and group aggression. Like humans, they will kill their neighbor to gain land, and they grieve over dead relatives (C. A. Anderson et al., 2010; D. Biro et al., 2010; Mitani et al., 2010). Elephants have demonstrated self-

So there is no question that other species display many remarkable cognitive skills. Are they also capable of what we humans call language, the topic we consider next?