9.2 Hunger

As dieters know, physiological needs are powerful. Their strength was vividly demonstrated when Ancel Keys and his research team (1950) did a now-

As Maslow might have guessed, the men became obsessed with food. They talked about it. They daydreamed about it. They collected recipes, read cookbooks, and feasted their eyes on tasty but forbidden food. Focused on their unmet basic need, they lost interest in sex and social activities. One man reported, “If we see a show, the most interesting [parts are] scenes where people are eating. I couldn’t laugh at the funniest picture in the world, and love scenes are completely dull.” As journalist Dorothy Dix (1861–

Motives can capture our consciousness. When we’re hungry, thirsty, fatigued, or sexually aroused, little else seems to matter. When we’re not, food, water, sleep, or sex just don’t seem like such big things in life, now or ever. (You may recall from Chapter 7 a parallel effect of our current good or bad mood on our memories.) Shop for food on an empty stomach and you are more likely to see those jelly-

The Physiology of Hunger

LOQ 9-

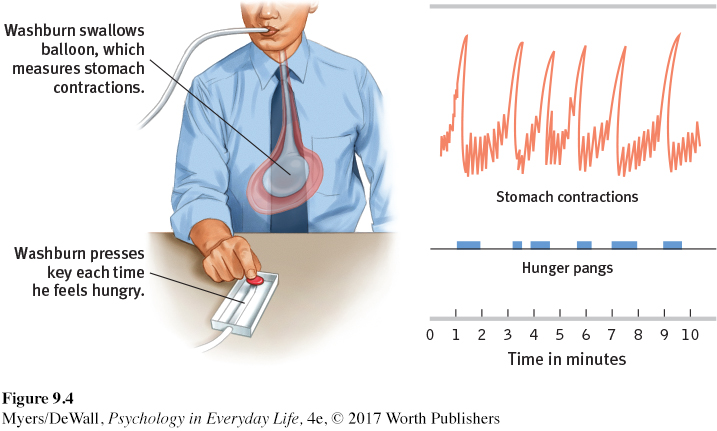

Deprived of a normal food supply, Keys’ volunteers were clearly hungry. What triggers hunger? Is it the pangs of an empty stomach? So it seemed to A. L. Washburn. Working with Walter Cannon, Washburn agreed to swallow a balloon that was attached to a recording device (Cannon & Washburn, 1912) (FIGURE 9.4). When inflated to fill his stomach, the balloon tracked his stomach contractions. Washburn supplied information about his feelings of hunger by pressing a key each time he felt a hunger pang. The discovery: When Washburn felt hungry, he was indeed having stomach contractions.

Can hunger exist without stomach pangs? To answer that question, researchers removed some rats’ stomachs and created a direct path to their small intestines (Tsang, 1938). Did the rats continue to eat? Indeed they did. Some hunger similarly persists in humans whose stomachs have been removed as a treatment for ulcers or cancer. So the pangs of an empty stomach cannot be the only source of hunger. What else might trigger hunger?

Body Chemistry and the Brain

glucose the form of sugar that circulates in the blood and provides the major source of energy for body tissues. When its level is low, we feel hunger.

Somehow, somewhere, your body is keeping tabs on the energy it takes in and the energy it uses. This balancing act enables you to maintain a stable body weight. A major source of energy in your body is the glucose circulating in your bloodstream. If your blood glucose level drops, you won’t consciously feel the lower blood sugar. But your brain, which automatically monitors your blood chemistry and your body’s internal state, will trigger your feeling of hunger.

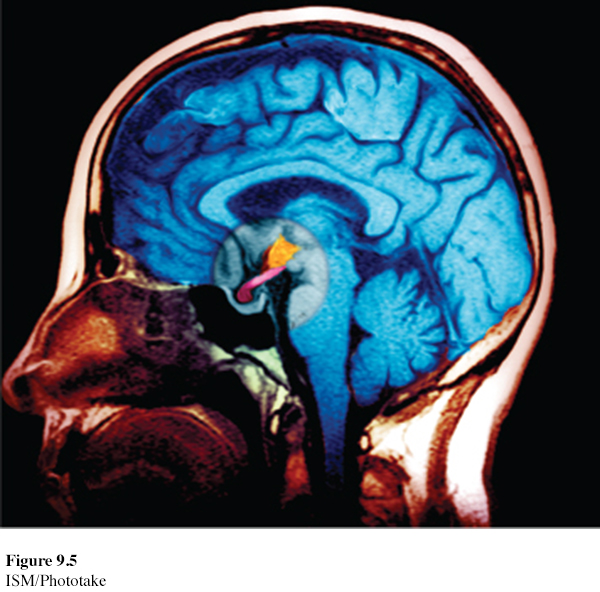

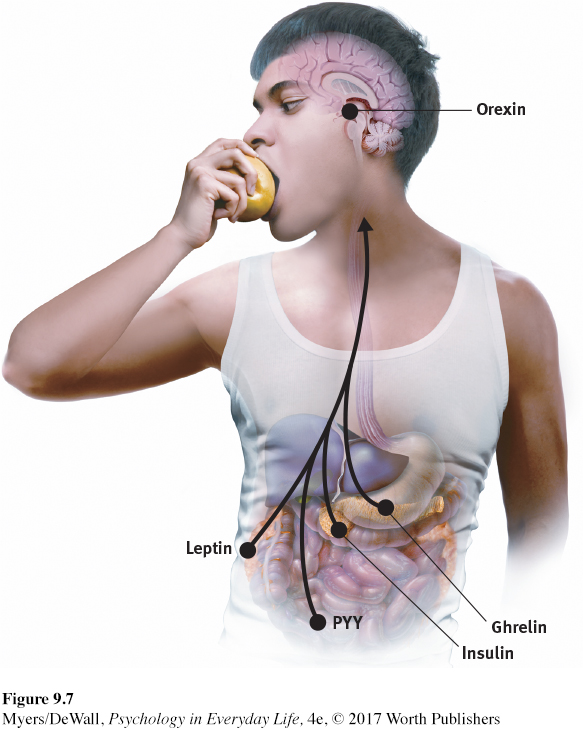

How does the brain sound the alarm? The work is done by several neural areas, some housed deep in the brain within the hypothalamus (FIGURE 9.5). This neural traffic intersection includes areas that influence eating. In one neural area (called the arcuate nucleus), a center pumps out appetite-

Blood vessels connect the hypothalamus to the rest of the body, so it can respond to our current blood chemistry and other incoming information. One of its tasks is monitoring levels of appetite hormones, such as ghrelin, a hunger-

set point the point at which your “weight thermostat” may be set. When your body falls below this weight, increased hunger and a lowered metabolic rate may combine to restore lost weight.

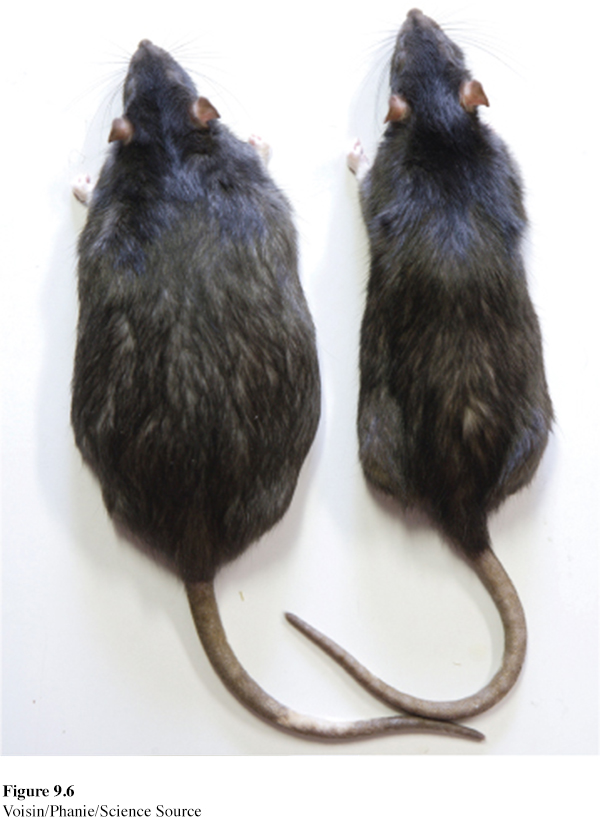

The interaction of appetite hormones and brain activity suggests that the body has a “weight thermostat.” When semistarved rats fall below their normal weight, this system signals their bodies to restore the lost weight. It’s like fat cells cry out, “Feed me!” and start grabbing glucose from the bloodstream (Ludwig & Friedman, 2014). Hunger increases and energy output decreases. If body weight rises—

basal metabolic rate the body’s resting rate of energy output.

We humans (and other species, too) vary in our basal metabolic rate, a measure of how much energy we use to maintain basic body functions when our body is at rest. But we share a common response to decreased food intake: Our basal metabolic rate drops. So it did for the participants in Keys’ experiment. After 24 weeks of semistarvation, they stabilized at three-

Some researchers have suggested that the idea of a biologically fixed set point is too rigid to explain why slow, steady changes in body weight can alter a person’s set point (Assanand et al., 1998), or why, when we have unlimited access to various tasty foods, we tend to overeat and gain weight (Raynor & Epstein, 2001). Thus, some researchers prefer the looser term settling point to indicate the level at which a person’s weight settles in response to caloric intake and energy use. As we will see next, environment matters as well as biology.

For an interactive and visual tutorial on the brain and eating, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Hunger and the Fat Rat.

For an interactive and visual tutorial on the brain and eating, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Hunger and the Fat Rat.

Retrieve + Remember

Question 9.3

•Hunger occurs in response to ______ (low/high) blood glucose and _____ (low/high) levels of ghrelin.

ANSWERS: low; high

The Psychology of Hunger

LOQ 9-

Our internal hunger games are pushed by our body chemistry and brain activity. Yet there is more to hunger than meets the stomach. This was strikingly apparent when trickster researchers tested two patients who had no memory for events occurring more than a minute ago (Rozin et al., 1998). If offered a second lunch 20 minutes after eating a normal lunch, both patients readily ate it . . . and usually a third meal offered 20 minutes after they finished the second. This suggests that one part of our decision to eat is our memory of the time of our last meal. As time passes, we think about eating again, and that thought triggers feelings of hunger. Psychological influences on eating behavior affect all of us at some point.

Taste Preferences: Biology and Culture

Both body cues and environment influence our feelings of hunger and what we hunger for—

Our preferences for sweet and salty tastes are genetic and universal. Other taste preferences are learned. People given highly salted foods, for example, develop a liking for excess salt (Beauchamp, 1987). People who become violently ill after eating a particular food often develop a dislike of it. (The frequency of children’s illnesses provides many chances for them to learn to avoid certain foods.)

Our culture teaches us what foods are acceptable. Many Japanese people enjoy nattó, a fermented soybean dish that “smells like the marriage of ammonia and a tire fire,” reports smell expert Rachel Herz (2012). Asians, she adds, are often repulsed by what many Westerners love—

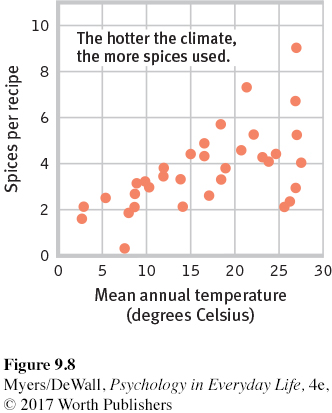

We also may learn to prefer some tastes because they are adaptive. In hot climates, where food spoils more quickly, recipes often include spices that slow the growth of bacteria (FIGURE 9.8). India averages nearly 10 spices per meat recipe, Finland 2 spices. Pregnancy-

Rats tend to avoid unfamiliar foods (Sclafani, 1995). So do we, especially those that are animal-

Tempting Situations

Would it surprise you to know that situations also control your eating? Some examples:

Friends and food Do you eat more when eating with others? Most of us do (Herman et al., 2003; Hetherington et al., 2006). The presence of others tends to amplify our natural behavior tendencies. (This is social facilitation and you’ll hear more about it in Chapter 11.)

Page 264Serving size is significant Researchers studied the effects of portion size by offering people varieties of free snacks (Geier et al., 2006). In an apartment lobby, they laid out full or half pretzels, big or little Tootsie Rolls, or a small or large serving scoop by a bowl of M&M’s. Their consistent result: Offered a supersized portion, people put away more calories. Offered pasta, people eat more when given a bigger plate (Van Ittersum & Wansink, 2012). Offered ice cream, people take and eat more when given a big bowl and big scoop. They pour and drink more from short, wide glasses than from tall, narrow glasses. Portion size matters.

Selections stimulate Food variety promotes eating. Offered a dessert buffet, people eat more than they do when choosing a portion from one favorite dessert. And they take more of easier-

to- reach foods on buffet lines (Marteau et al., 2012). For our early ancestors, eating more when foods were abundant and varied was adaptive. Consuming a wide range of vitamins and minerals and storing fat offered protection later, during winter cold or famine. When bad times hit, they could eat less, hoarding their small food supply until winter or famine ended (Polivy et al., 2008; Remick et al., 2009). Nudging nutrition One research team quadrupled carrots taken by offering schoolchildren carrots before they picked up other foods in a lunch line (Redden et al., 2015). A planned new school lunch tray will put fruits and veggies up front, and spread the main dish out in a shallow compartment to make it look bigger (Wansink, 2014). Such “nudges” support U.S. President Barack Obama’s 2015 executive order to use “behavioral science insights to better serve the American people.”

Consider how researchers test some of these ideas with LaunchPad’s IMMERSIVE LEARNING: How Would You Know If Using Larger Dinner Plates Makes People Gain Weight?

Consider how researchers test some of these ideas with LaunchPad’s IMMERSIVE LEARNING: How Would You Know If Using Larger Dinner Plates Makes People Gain Weight?

Retrieve + Remember

Question 9.4

•After an 8-

ANSWER: You have learned to respond to the sight and aroma that signal the food about to enter your mouth. Both physiological cues (low blood sugar) and psychological cues (anticipation of the tasty meal) heighten your experienced hunger.

Obesity and Weight Control

LOQ 9-

Obesity has physical health risks, but it can also be socially toxic, by affecting both how you feel about yourself and how others treat you. In fat-

The Survival Value—and Health Risks—of Fat

The answers lie partly in our history. Fat is stored energy. It is a fuel reserve that can carry us through times when food is scarce. (Think of that spare tire around the middle as an energy storehouse—

Our hungry distant ancestors were well served by a simple rule: When you find energy-

Significant obesity can shorten your life, reduce your quality of life, and increase your health care costs (Kitahara et al., 2014). It increases the risk of diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, gallstones, arthritis, and certain types of cancer. Women’s obesity has been linked to a higher risk of late-

So why don’t obese people just drop that excess baggage? Because their bodies fight back.

A SLUGGISH METABOLISM Once we become fat, we require less food to maintain our weight than we did to gain it. Compared with muscle tissue, fat has a lower metabolic rate—

Lean people and overweight people differ in their rates of resting metabolism. Lean people seem naturally disposed to move about, and in doing so, they burn more calories. Overweight people tend to sit still longer and conserve their energy (Levine et al., 2005). This helps explain why two people of the same height and age can maintain the same weight, even if one of them eats much more than the other does. (Who said life is fair?)

A GENETIC HANDICAP It’s true: Our genes influence the size of our jeans. Consider:

Adopted children share meals with their adoptive siblings and parents. Yet their body weights more closely resemble those of their biological family (Grilo & Pogue-

Geile, 1991). Identical twins have closely similar weights, even when raised apart (Plomin et al., 1997; Stunkard et al., 1990). Fraternal twins’ weights are much less similar. Such findings suggest that genes explain two-

thirds of the person- to- person differences in body mass (Maes et al., 1997).

As with other behavior traits, there is no one “weight gene.” Rather, many genes (including nearly 100 genes identified in a recent study) each contribute small effects (Locke et al., 2015).

See LaunchPad’s Video: Twin Studies for a helpful tutorial animation.

See LaunchPad’s Video: Twin Studies for a helpful tutorial animation.

SLEEP, FRIENDS, FOOD, ACTIVITY—

Studies in Europe, Japan, and the United States show that children and adults who suffer from sleep loss are more at risk for obesity (Keith et al., 2006; Nedeltcheva et al., 2010; Taheri, 2004; Taheri et al., 2004). Deprived of sleep, our bodies produce less leptin (which reports body fat to the brain) and more ghrelin (the appetite-

Social influence is another factor. One 32-

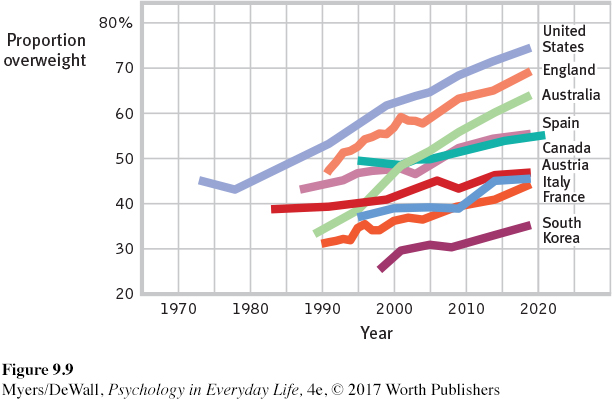

Friends matter, but evidence that environment influences weight comes from eating disorders research (see Chapter 13), and especially from our fattening world (FIGURE 9.9). What explains this growing problem? Changing food consumption and activity levels are at work. Our lifestyles may now approach those of animal feedlots, where farmers fatten animals by giving them lots of food and little exercise. We are eating more and moving less. In the United States, jobs requiring moderate physical activity declined from about 50 percent in 1960 to 20 percent in 2011 (Church et al., 2011).

Stadiums, theaters, and subway cars—

* * *

The obesity research findings reinforce a familiar lesson from Chapter 8’s study of intelligence. There can be high levels of heritability (genetic influence on individual differences) without heredity being the only explanation of group differences. Genes mostly determine why one person today is heavier than another. Environment mostly determines why people today are heavier than their counterparts 50 years ago.

Our eating behavior once again demonstrates one of this book’s big ideas: Biological, psychological, and social-

|

People struggling with obesity should seek medical evaluation and guidance. For others who wish to lose weight, researchers have offered these tips: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Retrieve + Remember

Question 9.5

•Why can two people of the same height, age, and activity level maintain the same weight, even if one of them eats much less than the other does?

ANSWER: Individuals have very different set points and genetically influenced metabolism levels, causing them to burn calories differently.