9.4 Emotion: Arousal, Behavior, and Cognition

LOQ 9-

Motivated behavior is often connected to powerful emotions. My [DM’s] own need to belong was unforgettably disrupted one day when I went to a huge store and brought along Peter, my toddler first-

With mild anxiety, I peered around one end of the customer service counter. No Peter in sight. With slightly more anxiety, I peered around the other end. No Peter there, either. Now, with my heart pounding, I circled the neighboring counters. Still no Peter anywhere. As anxiety turned to panic, I began racing up and down the store aisles. He was nowhere to be found. Seeing my alarm, the store manager used the public-

But then, as I passed the counter yet again, there he was, having been found and returned by some obliging customer! In an instant, the arousal of terror spilled into ecstasy. Clutching my son, with tears suddenly flowing, I found myself unable to speak my thanks and stumbled out of the store awash in grateful joy.

Where do such emotions come from? Why do we have them? What are they made of? Emotions don’t exist just to give us interesting experiences. They are our body’s adaptive response, supporting our survival. When we face challenges, emotions focus our attention and energize our action (Cyders & Smith, 2008). Our heart races. Our pace quickens. All our senses go on high alert. Receiving unexpected good news, we may find our eyes tearing up. We raise our hands in triumph. We feel joy and a newfound confidence.

emotion a response of the whole organism, involving (1) bodily arousal, (2) expressive behaviors, and (3) conscious experience.

As my panicked search for Peter illustrates, emotions are a mix of

bodily arousal (heart pounding),

expressive behaviors (quickened pace), and

conscious experience, including thoughts (“Is this a kidnapping?”) and feelings (fear, panic, joy).

Psychologists’ task is fitting these three pieces together. To do that, we need answers to two big questions:

A chicken-

and- egg debate: Does your bodily arousal come before or after your emotional feelings? (Did I first notice my racing heart and faster step, and then feel terror about losing Peter? Or did my sense of fear come first, stirring my heart and legs to respond?) Page 271How do thinking (cognition) and feeling interact? Does cognition always come before emotion? (Did I think about a kidnapping threat before I reacted emotionally?)

Historical theories of emotion, as well as current research, have tried to answer these questions.

Historical Emotion Theories

The psychological study of emotion began with the first question: How do bodily responses relate to emotions? Two historical theories provided different answers.

James-Lange Theory: Arousal Comes Before Emotion

James-

Common sense tells most of us that we cry because we are sad, lash out because we are angry, tremble because we are afraid. First comes conscious awareness, then the feeling. But to psychologist William James, an early explorer of human feelings, this commonsense view of emotion had things backward. Rather, “We feel sorry because we cry, angry because we strike, afraid because we tremble” (1890, p. 1066). James’ idea was also proposed by Danish physiologist Carl Lange, and so is called the James-

Cannon-Bard Theory: Arousal and Emotion Happen at the Same Time

Cannon-

Physiologist Walter Cannon (1871–

But are they really independent from each other? The Cannon-

But our emotions also involve cognition (Averill, 1993; Barrett, 2006). Here we arrive at psychology’s second big emotion question: How do thinking and feeling interact? Whether we fear the man behind us on the dark street depends entirely on whether we interpret his actions as threatening or friendly.

Schachter-Singer Two-Factor Theory: Arousal + Label = Emotion

two-

Stanley Schachter and Jerome Singer (1962) demonstrated that how we assess, or appraise, our experiences matters greatly. Our physical reactions and our thoughts (perceptions, memories, and interpretations) together create emotion. In their two-

Sometimes our arousal spills over from one event to the next, influencing our response. Imagine arriving home after a fast run and finding a message that you got a longed-

To explore this spillover effect, Schachter and Singer injected college men with epinephrine, a hormone that triggers feelings of arousal. Picture yourself as a participant. After receiving the injection, you go to a waiting room. You find yourself with another person (actually someone working with the experimenters) who is acting either joyful or irritated. As you observe this accomplice, you begin to feel your heart race, your body flush, and your breathing become more rapid. If you had been told to expect these effects from the injection, what would you feel? The actual volunteers felt little emotion—

For a 4-

For a 4-

We can experience a stirred-

The point to remember: Arousal fuels emotion; cognition channels it.

Zajonc, LeDoux, and Lazarus: Emotion and the Two-Track Brain

Is the heart always subject to the mind? Must we always interpret our arousal before we can experience an emotion? No, said Robert Zajonc (1923–

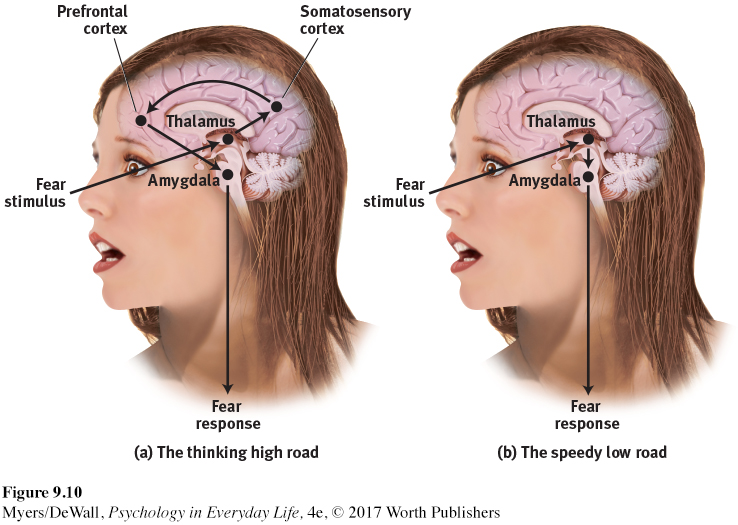

Our emotional responses are the final step in a process that can follow two different pathways in our brain, both via the thalamus. Some emotions, especially our more complex feelings, like hatred and love, travel a “high road” to the brain’s cortex (FIGURE 9.10). There, we analyze and label information before we order a response via the amygdala (an emotion-

But sometimes our emotions (especially simple likes, dislikes, and fears) take what Joseph LeDoux (2002, 2015) has called the “low road.” This neural shortcut bypasses the cortex (FIGURE 9.10b). Following the low road, a fear-

The amygdala’s structure makes it easier for our feelings to hijack our thinking than for our thinking to rule our feelings (LeDoux & Armony, 1999). It sends more neural projections up to the cortex than it receives back. In the forest, we can jump when we hear rustling in nearby bushes and leave it to our cortex (via the high road) to decide later whether the sound was made by a snake or by the wind. Such experiences support Zajonc’s belief that some of our emotional reactions involve no deliberate thinking.

Emotion researcher Richard Lazarus (1991, 1998) agreed that our brain processes vast amounts of information without our conscious awareness, and that some emotional responses do not require conscious thinking. Much of our emotional life operates via the automatic, speedy low road. But, he asked, how would we know what we are reacting to if we did not in some way appraise the situation? The appraisal may be effortless and we may not be conscious of it, but it is still a mental function. To know whether a stimulus is good or bad, the brain must have some idea of what it is (Storbeck et al., 2006). Thus, said Lazarus, emotions arise when we appraise an event as harmless or dangerous, whether we truly know it is or not. We appraise the sound of the rustling bushes as the presence of a threat. Later, we learn that it was “just the wind.”

Let’s sum up (see also TABLE 9.3). As Zajonc and LeDoux have demonstrated, some emotional responses—

| Theory | Explanation of Emotions | Example |

|---|---|---|

| James- |

Our awareness of our specific bodily responses to emotion- |

We observe our heart racing after a threat and then feel afraid. |

| Cannon- |

Bodily responses + simultaneous subjective experience | Our heart races at the same time that we feel afraid. |

| Schachter- |

Two factors: general arousal + a conscious cognitive label | We may label our arousal as fear or excitement, depending on context. |

| Zajonc; LeDoux | Instant, before cognitive appraisal | We automatically feel startled by a sound in the forest before labeling it as a threat. |

| Lazarus | Appraisal (“Is it dangerous or not?”)—sometimes without our awareness— |

The sound is “just the wind.” |

But other emotions—

Retrieve + Remember

Question 9.8

•According to the Cannon-

ANSWERS: simultaneously; sequentially (first the physiological response, and then the experienced emotion)

Question 9.9

•According to Schachter and Singer, two factors lead to our experience of an emotion: (1) physiological arousal and (2) ____________ appraisal.

ANSWER: cognitive

Question 9.10

•Emotion researchers have disagreed about whether emotional responses occur in the absence of cognitive processing. How would you characterize the approach of each of the following researchers: Zajonc, LeDoux, Lazarus, Schachter, and Singer?

ANSWER: Zajonc and LeDoux suggested that we experience some emotions without any conscious, cognitive appraisal. Lazarus, Schachter, and Singer emphasized the importance of appraisal and cognitive labeling in our experience of emotion.