9.6 Expressed and Experienced Emotion

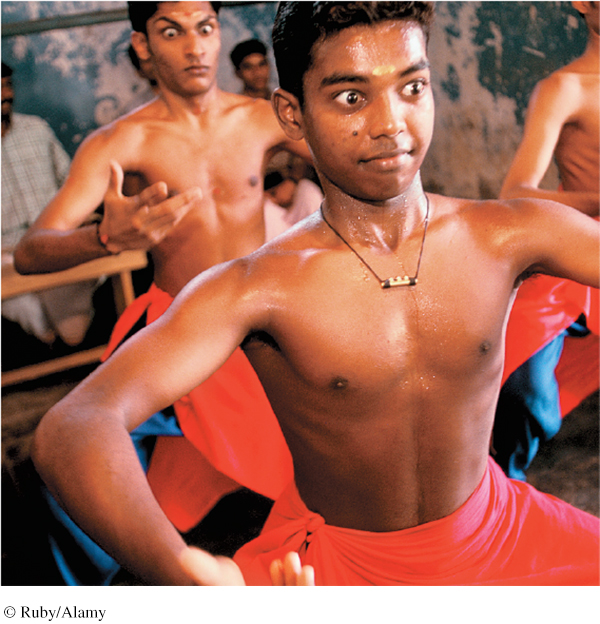

There is a simple method of detecting people’s emotions: Read their body language, listen to their voice tones, and study their faces. People’s expressive behavior reveals their emotion. Does this nonverbal language vary with culture, or is it the same everywhere? And do our expressions influence what we feel?

Detecting Emotion in Others

LOQ 9-

All of us communicate without words. Westerners “read” a firm handshake as evidence of an outgoing, expressive personality (Chaplin et al., 2000). A glance can communicate intimacy, while darting eyes may signal anxiety (Kleinke, 1986; Perkins et al., 2012). When two people are passionately in love, they typically spend time—

Most of us read nonverbal cues fairly well. Shown 10 seconds of video from the end of a speed-

Despite our brain’s emotion-

Some of us are, however, more skilled than others at reading emotions. In one study, hundreds of people were asked to name the emotion displayed in brief film clips. The clips showed portions of a person’s emotionally expressive face or body, sometimes accompanied by a garbled voice (Rosenthal et al., 1979). For example, one 2-

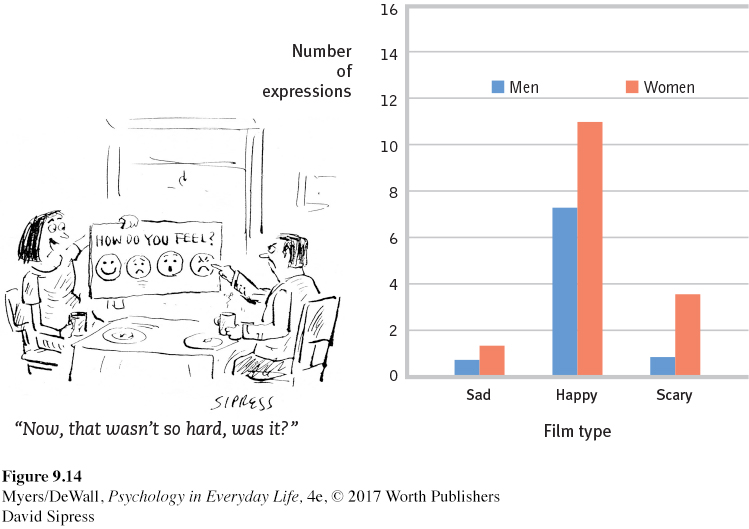

Women’s skill at decoding emotions may help explain why women tend to respond with and express greater emotion (Fischer & LaFrance, 2015; Vigil, 2009). In studies of 23,000 people from 26 cultures, women more than men have reported themselves open to feelings (Costa et al., 2001). Children show the same gender difference: Girls express stronger emotions than boys do (Chaplin & Aldao, 2013). That helps explain the extremely strong perception (nearly all 18-

One exception: Quickly—

Are there gender differences in empathy? If you have empathy, you identify with others and imagine what it must be like to walk in their shoes. You rejoice with those who rejoice and weep with those who weep. In surveys, women are far more likely than men to describe themselves as empathic. But measures of body responses, such as one’s heart rate while seeing another’s distress, reveal a much smaller gender gap (Eisenberg & Lennon, 1983; Rueckert et al., 2010).

Nevertheless, females are somewhat more likely to express empathy—

Retrieve + Remember

Question 9.11

•_____(Women/Men) report experiencing emotions more deeply, and they tend to be more adept at reading nonverbal behavior.

ANSWER: Women

Culture and Emotion

LOQ 9-

The meaning of gestures varies from culture to culture. U.S. President Richard Nixon learned this while traveling in Brazil. He made the North American “A-

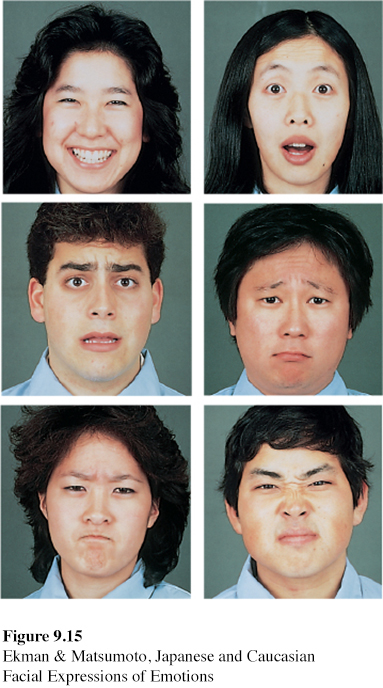

Do facial expressions also have different meanings in different cultures? To find out, researchers showed photographs of some facial expressions to people in different parts of the world and asked them to guess the emotion (Ekman, 1994; Ekman & Friesen, 1975; Ekman et al., 1987; Izard, 1977, 1994). You can try this matching task yourself by pairing the six emotions with the six faces in FIGURE 9.15.

Question 9.12

From left to right, top to bottom: happiness, surprise, fear, sadness, anger, disgust.

Regardless of your cultural background, you probably did pretty well. A smile’s a smile the world around. Ditto for sadness, and to a lesser extent the other basic expressions (Jack et al., 2012). (There is no culture where people frown when they are happy.) We do slightly better when judging emotional displays from our own culture (Elfenbein & Ambady, 2002, 2003a,b). Nevertheless, the outward signs of emotion are generally the same across cultures.

Musical expressions of emotions also cross cultures. Happy and sad music feel happy and sad around the world. Whether you live in an African village or a European city, fast-

Do these shared emotional categories reflect shared cultural experiences, such as movies and TV programs that are seen around the world? Apparently not. Paul Ekman and Wallace Friesen (1971) asked isolated people in New Guinea to respond to such statements as, “Pretend your child has died.” When North American college students viewed the recorded responses, they easily read the New Guineans’ facial reactions.

So we can say that facial muscles speak a fairly universal language. This discovery would not have surprised Charles Darwin (1809–

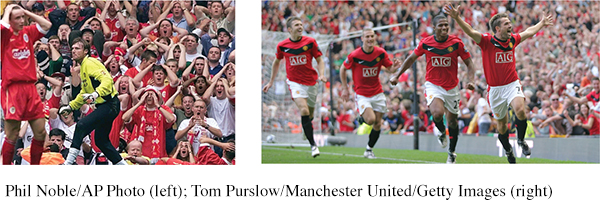

Smiles are social as well as emotional events. Olympic gold medalists typically don’t smile when they are awaiting their award ceremony. But they wear broad grins when interacting with officials and facing the crowd and cameras (Fernández-

“For news of the heart, ask the face.”

Guinean proverb

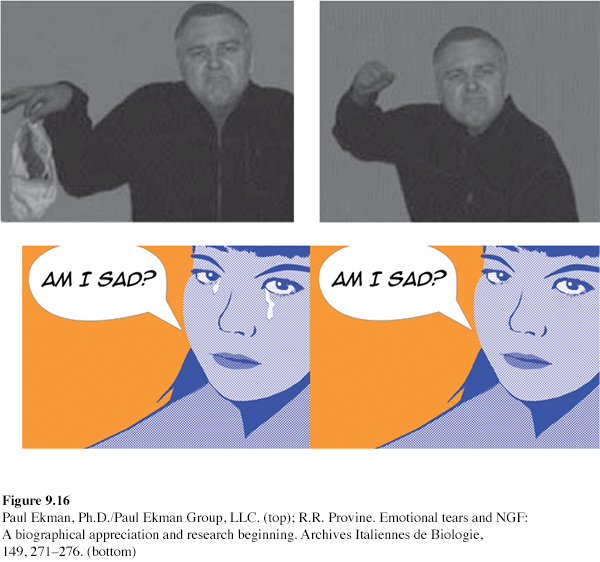

Although we humans share a universal facial language, it has been adaptive for us to interpret faces in particular contexts (FIGURE 9.16). People judge an angry face set in a frightening situation as afraid, and a fearful face set in a painful situation as pained (Carroll & Russell, 1996). Movie directors harness this tendency by creating scenes and soundtracks that amplify our perceptions of particular emotions.

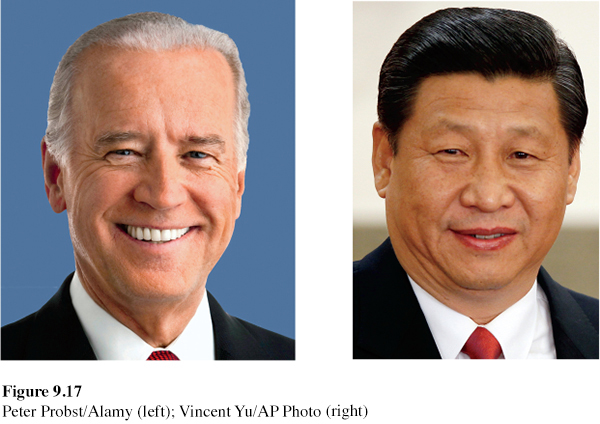

Smiles are also cultural events. In the United States, people of European descent tend to display excitement; in China, people are more likely to emphasize calmness (Tsai et al., 2006). These cultural differences shape facial expressiveness (Tsai et al., 2016). Compared with their counterparts in China, European-

For a 4-

For a 4-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 9.13

•Are people more likely to differ culturally in their interpretations of facial expressions, or of gestures?

ANSWER: gestures

The Effects of Facial Expressions

LOQ 9-

As famed psychologist William James (1890) struggled with feelings of depression and grief, he came to believe that we can control our emotions by going “through the outward movements” of any emotion we want to experience. “To feel cheerful,” he advised, “sit up cheerfully, look around cheerfully, and act as if cheerfulness were already there.”

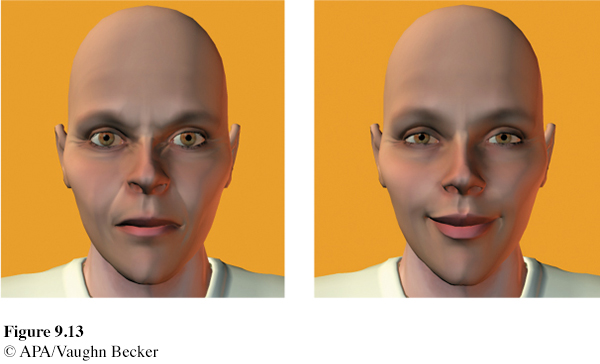

Was James right? Can our outward expressions and movements trigger our inner feelings and emotions? You can test his idea: Fake a big grin. Now scowl. Can you feel the “smile therapy” difference? Participants in dozens of experiments have felt a difference. For example, researchers tricked students into making a frowning expression by asking them to “contract these muscles” and “pull your brows together” (Laird, 1974, 1984; Laird et al., 1989). (The students thought they were helping the researchers attach facial electrodes.) The result? The students reported feeling a little angry.

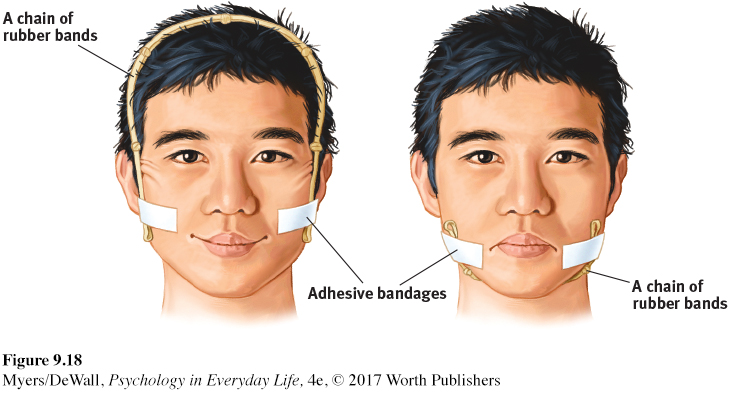

facial feedback effect the tendency of facial muscle states to trigger corresponding feelings such as fear, anger, or happiness.

So, too, for other basic emotions. For example, people reported feeling more fear than anger, disgust, or sadness when made to construct a fearful expression (Duclos et al., 1989). (They were told, “Raise your eyebrows. And open your eyes wide. Move your whole head back, so that your chin is tucked in a little bit, and let your mouth relax and hang open a little.”) This facial feedback effect has been found many times, in many places, for many basic emotions (FIGURE 9.18). Just activating one of the smiling muscles by holding a pen in the teeth (rather than gently in the mouth, which produces a neutral expression) makes stressful situations less upsetting (Kraft & Pressman, 2012). When happy we smile, and when smiling we become happier.

Retrieve + Remember

Question 9.14

ANSWERS: (1) Most report feeling more happy than sad when their cheeks are raised upward. (2) Most report feeling more sad than happy when their cheeks are pulled downward.

So, your face is more than a billboard that displays your feelings; it also feeds your feelings. No wonder some depressed patients reportedly feel better after between-

Other studies have noted a similar behavior feedback effect (Carney et al., 2015; Flack, 2006). Try it. Walk for a few minutes with short, shuffling steps, keeping your eyes downcast. Now walk around taking long strides, with your arms swinging and your eyes looking straight ahead. Can you feel your mood shift? Going through the motions awakens the emotions.

You can use your understanding of feedback effects to become more empathic—

* * *

We have seen how our motivated behaviors, triggered by the forces of nature and nurture, often go hand in hand with emotional responses. Our psychological emotions likewise come equipped with physical reactions. Nervous about an upcoming date, we feel stomach butterflies. Anxious over public speaking, we head for the bathroom. Smoldering over a family conflict, we get a splitting headache. Negative emotions and the prolonged high arousal that may accompany them can tax the body and harm our health. You’ll hear more about this in Chapter 10. In that chapter, we’ll also take a closer look at the emotion of happiness.