When it comes to species distributions, history matters. Species were not designed from scratch to fill a particular niche. Rather, whatever arrived in a geographic region first—

The study of the distribution patterns of living organisms around the world is called biogeography. This is the second line of evidence that helps us to see that evolution takes place and to better understand the process. The patterns of biogeography that Darwin and many subsequent researchers noticed provide strong evidence that evolutionary forces are responsible for these patterns. Species often more closely resemble other species that live less than a hundred miles away but in radically different habitats than they resemble species living thousands of miles away in nearly identical habitats. In Hawaii, for example, nearly every bird is some sort of modified honeycreeper, from seed-

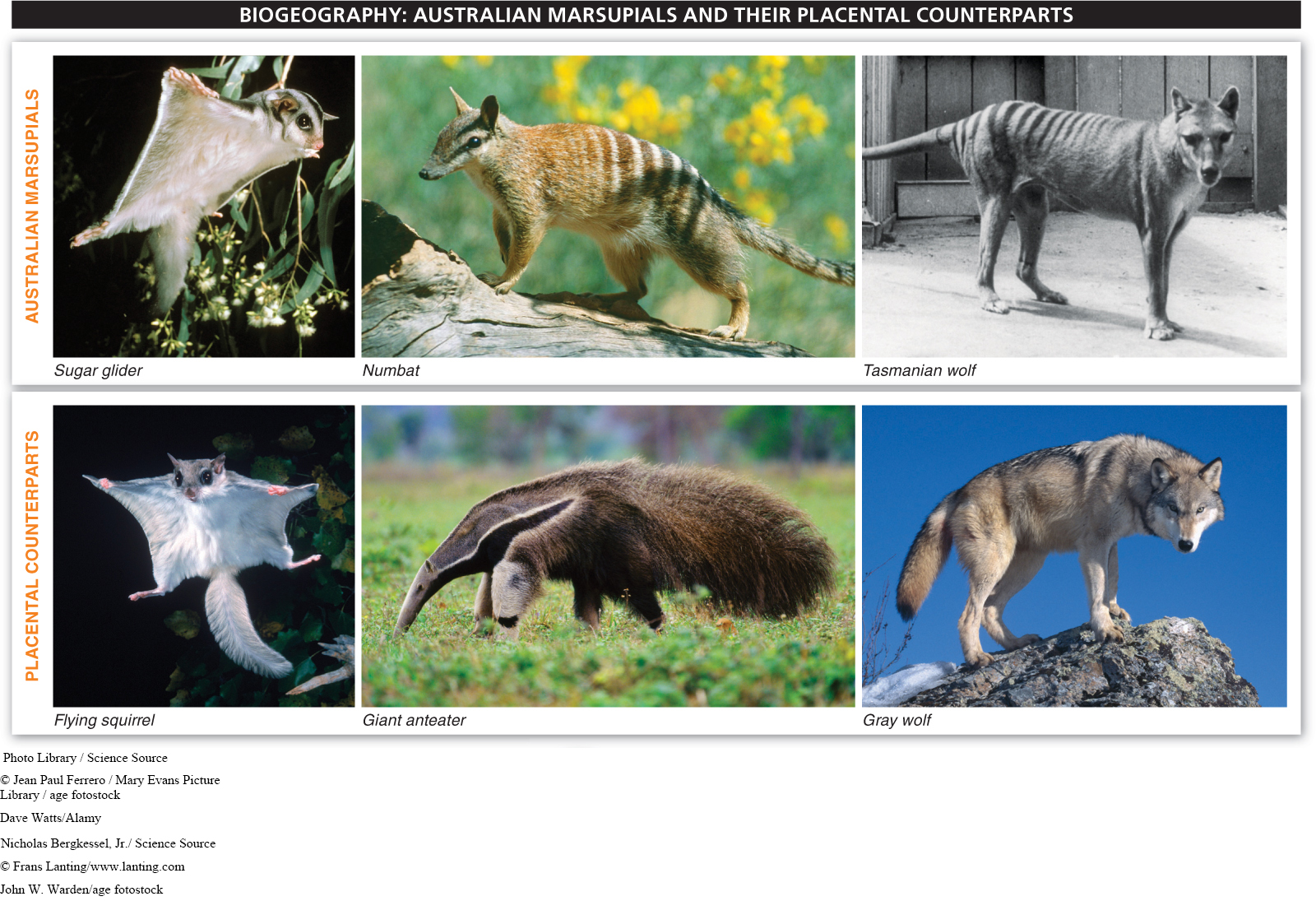

Large, isolated habitats also have interesting biogeographic patterns. Australia and Madagascar are filled with unique organisms that are clearly not closely related to organisms elsewhere. In Australia, for example, marsupial species, rather than placental mammals, fill all of the usual roles. There are marsupial “wolves,” marsupial “mice,” marsupial “squirrels,” and marsupial “anteaters” (FIGURE 8-37).

The marsupials of Australia physically resemble their placental counterparts for most traits, but molecular analysis shows that they are actually more closely related to one another, sharing a common marsupial ancestor. Their relatedness to each other is also revealed by similarities in their reproduction: females give birth to offspring at a relatively early stage of development, and the offspring finish their development in a pouch. The presence of marsupials in Australia does not simply mean that marsupials are better adapted than placentals to Australian habitats. When placental organisms are transplanted to Australia they do just fine, often thriving to the point of endangering the native species. Instead, it appears that the terrestrial placental mammals in Australia disappeared about 55 million years ago—

352

Biogeographic patterns such as those seen in honeycreepers and in the marsupials of Australia illustrate that evolution doesn’t necessarily lead to the same “solutions” each time a particular set of environmental conditions occurs. Rather, the traits in populations that happen to be in a particular location gradually change, and those species become better adapted to the habitats they occupy.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 8.19

Observing geographic patterns of species distributions—

Why are most birds in Hawaii some form of honeycreeper?

The ancestor of the honeycreeper was introduced to these isolated islands from the mainland. This ancestor took up different lifestyles in different habitats, and each population adapted and evolved differently in each of these environments.