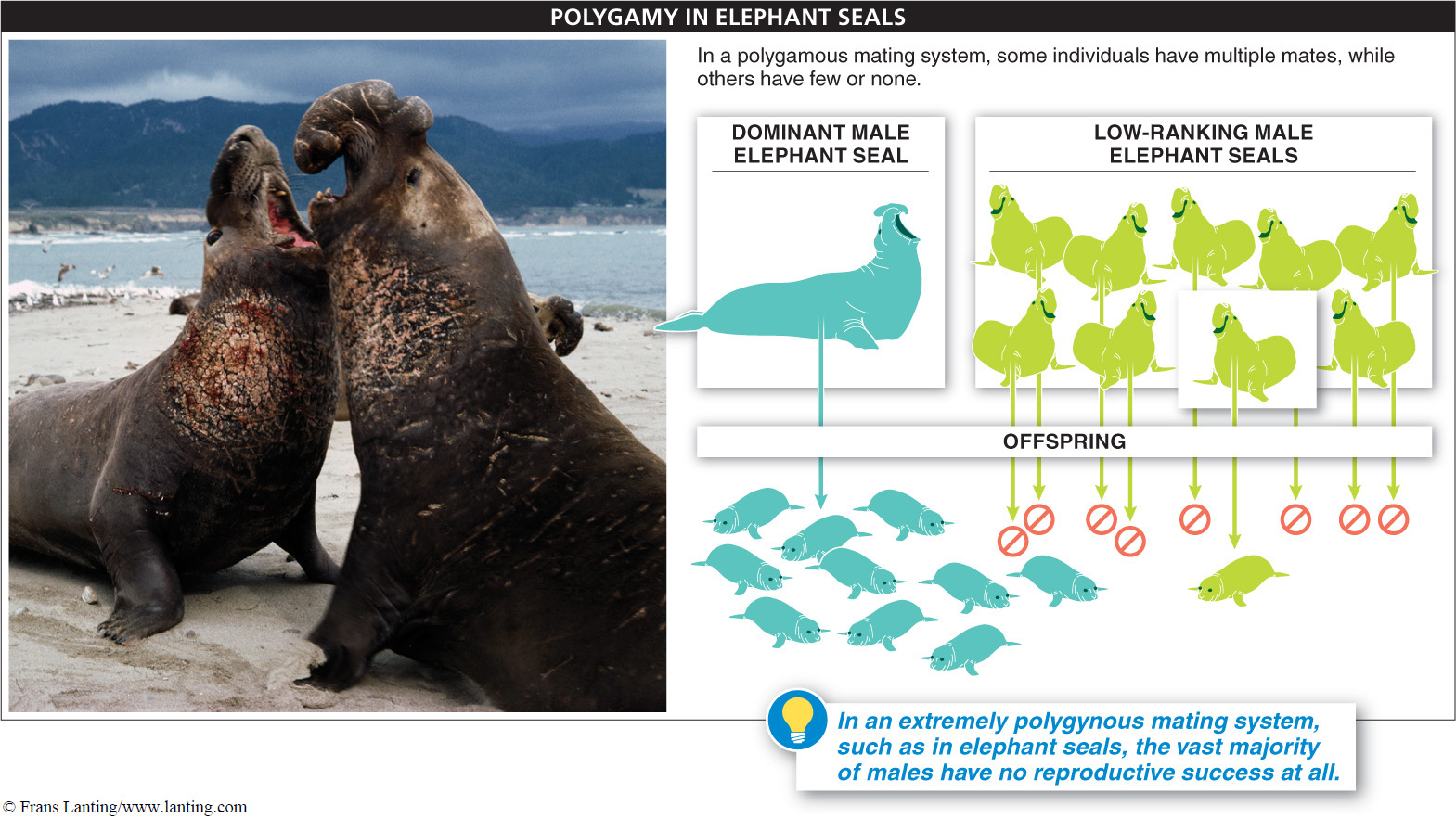

As we continue our tour of animal mating behavior, we turn again to the elephant seal. In December of each year, the males appear on islands off the coast of northern California, where they compete with each other for possession of the beach. Through bloody fights they establish dominance hierarchies, with the biggest males—

In mid-

The elephant seals’ mating pattern exemplifies polygamy, a system in which some individuals attract multiple mates while other individuals attract none. Polygamous mating systems can be subdivided into polygyny, in which individual males mate with multiple females, and polyandry, in which individual females mate with multiple males. Polygamy can be contrasted with monogamy, in which most individuals mate and remain with just one other individual. Polygamy and monogamy are two types of mating systems, which describe the patterns of mating behavior in a species. In this section, we explore the features of environments and species that influence mating systems and survey the range of mating systems observed in nature.

As we have seen, throughout the animal world, as a result of their relative parental investment, females are choosy about which males they mate with, and males compete for access to mating opportunities. Not surprisingly, multiple females often end up selecting the same male—

392

Identifying a population’s mating systems is not as easy as the elephant seal example might lead us to believe. Three issues, in particular, complicate the task. First, there are often differences between animals’ mating behavior and their bonding behavior. That is, it may seem that a male and female have formed a pair bond—in which they spend a high proportion of their time together, often over many years, sharing a nest or other “home” and contributing equally to parental care of offspring in what appears to be a monogamous relationship. Closer inspection (often including DNA analysis of the offspring), however, sometimes reveals that the male and/or the female may be mating with other individuals in the population, and perhaps the mating system is better described as a variation on polygamy. A second difficulty in defining a species’ mating system arises because the mating system may vary within the species. That is, some individuals may be monogamous, while others are polygamous. And the mating system may even change over the course of an individual’s life. A third difficulty is that males and females often differ in their mating behavior. In the elephant seals described above, it could be said that the females are all mating monogamously, while the males are polygamous.

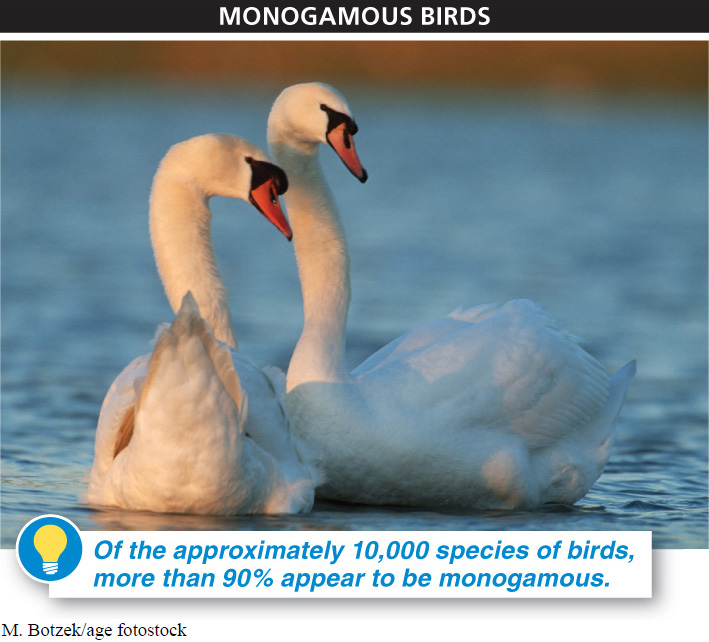

Examination of birds and mammals in general, however, reveals one sharp split. As we discussed in Section 9-

Are humans monogamous or polygamous?

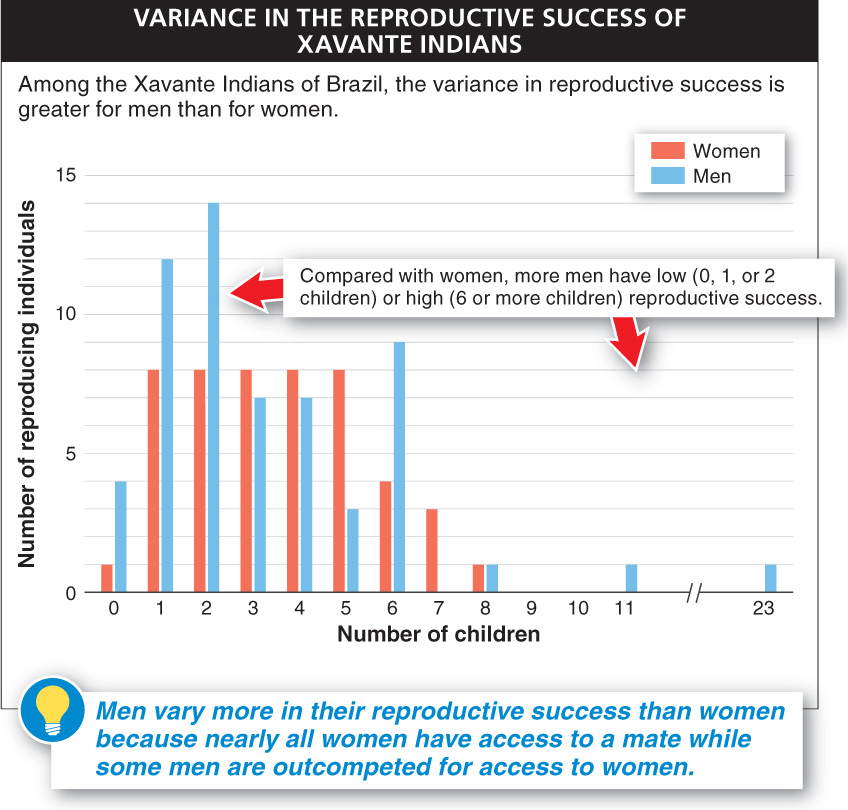

And what of humans? Across a variety of cultures, males consistently have greater variance in reproductive success than females—

393

Some differences in the variance in reproductive success among males and females, which can be significantly influenced by socialization and other cultural forces, are generally associated with polygynous mating systems. However, the difference between the sexes found in the Brazilian study is quite small when compared with many other mammalian species, such as elephant seals, and is close to that seen in populations with a monogamous mating system. Humans, consequently, seem to have a mating system close to, but not completely, monogamous.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 9.15

Mating systems—

How does parental investment correlate with mating patterns?

When males and females have similar parental investments, monogamy is common. When the parental investment of the female is much higher than that of the male, polygyny is common.