Even the greatest of success stories often owe something to a bit of luck. As mammals, it might seem that we owe a little of our success to luck. Flash back to 65 million years ago. Our mammalian ancestors had their place among the organisms on earth, but these rodent-

All that changed in an instant when the earth was struck by an asteroid, about 6 miles (10 km) in diameter, near what is now the eastern part of Mexico. This caused the environmental conditions on earth to change quickly and drastically. We’ll explore the details of this catastrophic event in the next section, but one outcome was extreme: almost all of the dinosaur species were wiped out. Our mammalian ancestors, though, survived and found themselves living on a planet where most of their competitors had suddenly disappeared. We were in the right place at the right time.

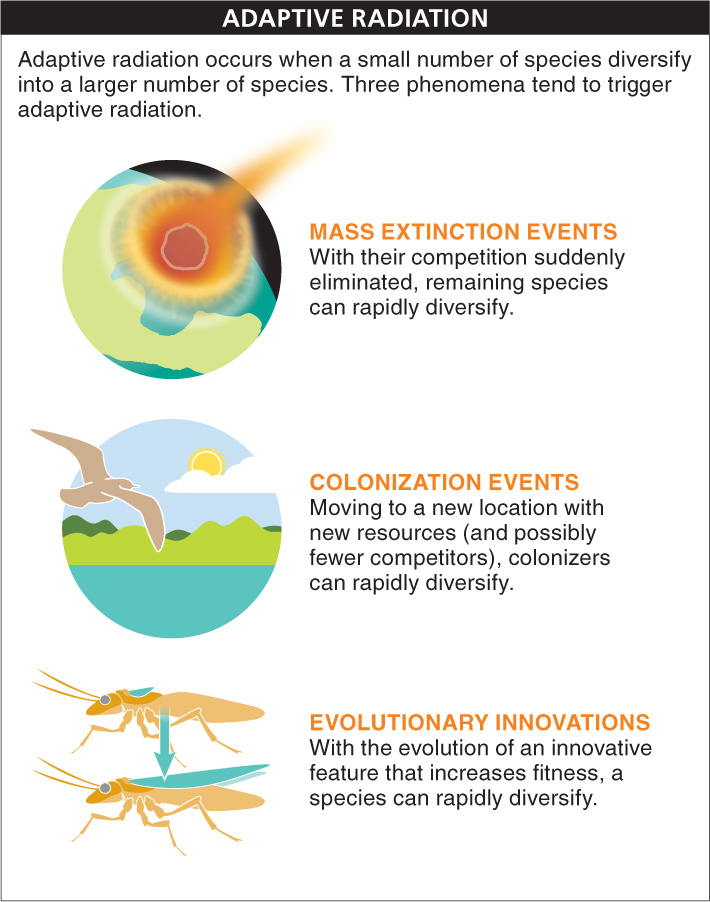

What followed was an explosive expansion of mammalian species. In a brief period of time, a small number of species diversified into a much larger number of species, able to live in a wide diversity of habitats. Called an adaptive radiation, such a large and rapid diversification has occurred many times throughout history (FIGURE 10-24).

429

Three different phenomena tend to trigger adaptive radiations. After one of these events, surviving species find themselves in locations where they suddenly have access to plentiful new resources.

1. Mass extinction events. With the near-

It is interesting to note that although, from time to time, sudden and extreme events lead to mass extinctions that wipe out a large proportion of the species on earth, in every case these mass extinctions are followed by a time of explosive speciation in the groups that survive

2. Colonization events. In a rare event, one or a few birds or small insects will fly off from a mainland and end up on a distant island group, such as Hawaii or the Galápagos Islands. Once there, they tend to find a large number of opportunities for adaptation and diversification. In the Galápagos, as we learned in Section 10-

3. Evolutionary innovations. In the world of computers, software developers are always looking for the “killer app”—the new application so useful that it immediately leads to huge success, opening up a large new niche in the software market or greatly expanding an already-

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 10.13

Adaptive radiations—

The textbook equates evolutionary innovations to the successes of “killer apps” in software, such as the first spreadsheet or web browser. In the world of computers, success is measured by finding a new market or greatly expanding an existing market. What is meant by “success” with regard to the “killer apps” of evolution?

Innovations, such as wings and the rigid outer skeleton in insects or flowers in plants, lead to success in the form of diversity and survival relative to others with whom they compete.

430