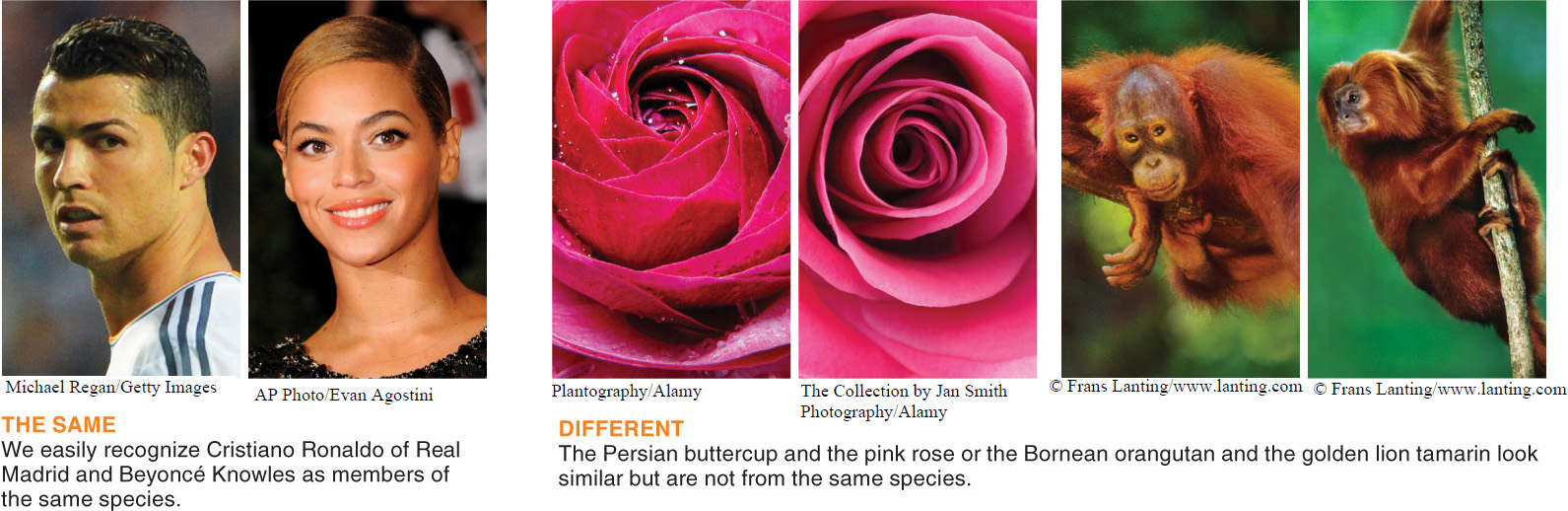

A cat and a mouse are different things. Oprah Winfrey and Bill Gates, on the other hand, are different versions of the same thing. That is, although they are different individuals, both are humans. We generally distinguish between different kinds of living organisms: a rose versus a daisy, a wasp versus a fly, a snake versus a frog. Similarly, we lump some organisms into the same group and recognize them as different versions of the same thing: red roses and yellow roses, Chihuahuas and Dalmatians. How do we know when to classify two individuals as members of different groups and when to classify them as members of the same group (FIGURE 10-5)?

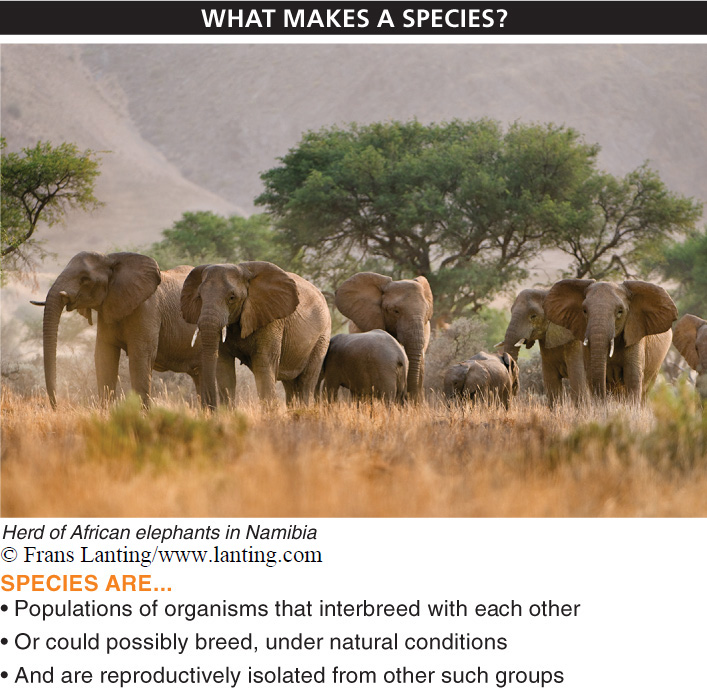

Biologists use the word species to label different kinds of organisms. According to the biological species concept, species are populations of organisms that interbreed, or could possibly interbreed, with each other under natural conditions, and that cannot interbreed with organisms from other such groups (FIGURE 10-6).

Notice that the biological species concept completely ignores physical appearance when defining a species and instead emphasizes reproductive isolation, the inability of individuals from two populations to produce fertile offspring with each other, thereby making it impossible for gene exchange between the populations to occur.

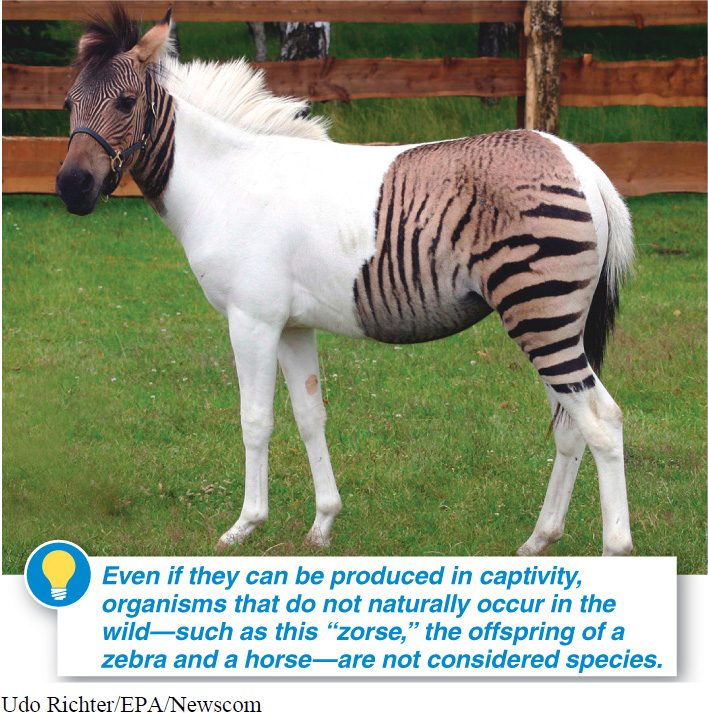

Let’s clarify two important features of the biological species concept. First, it says that members of a species are actually interbreeding or could possibly interbreed. This emphasis means that just because two individuals are physically separated, they aren’t necessarily of different species. A person living in the United States and a person living in Iceland, for example, may not be able to mate because of the distance, but if they were brought to the same location, they could. So, although the people are not in the same population, we do not consider them to be reproductively isolated. Second, our definition refers to “natural” conditions. This distinction is important because occasionally, in captivity, individuals may interbreed that would not interbreed in the wild, such as zebras and horses (FIGURE 10-7).

412

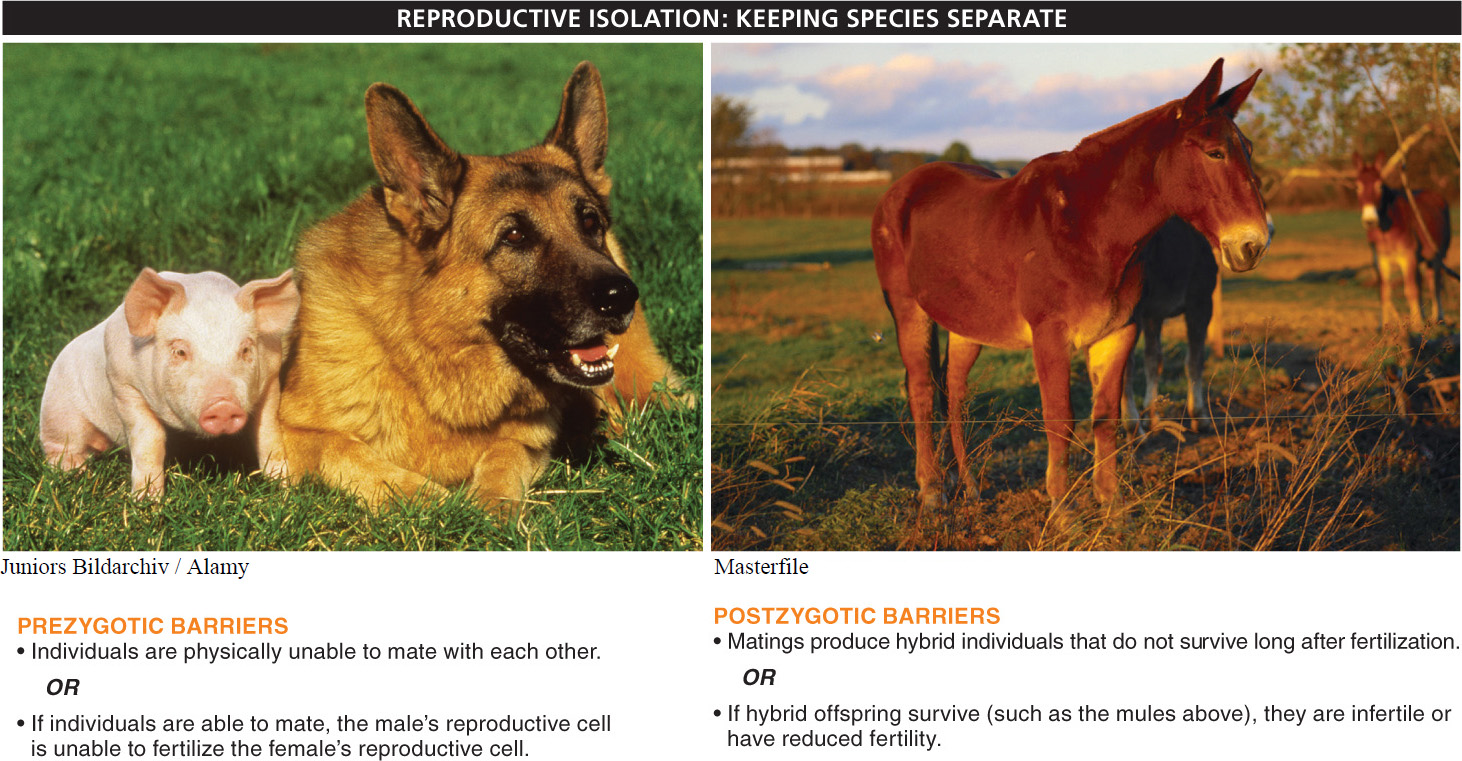

There are two types of barriers that prevent individuals of different species from reproducing: prezygotic and postzygotic barriers (FIGURE 10-8). (Remember, an egg that has been fertilized by a sperm cell is a zygote.)

413

Prezygotic barriers make it impossible for individuals to mate with each other or, if they can mate, make it impossible for the male’s reproductive cell to fertilize the female’s reproductive cell. These barriers include situations in which the members of the two species have different courtship rituals or have physical differences that prevent mating or fertilization.

Postzygotic barriers occur after fertilization and generally prevent the production of fertile offspring from individuals of two different species. These barriers are responsible for the production of hybrid individuals that either do not survive long after fertilization or, if they do, are infertile or have reduced fertility. Mules, for example, are the hybrid offspring of horses and donkeys, and although they can survive, they cannot produce their own offspring.

At first glance, the biological species concept seems to make it possible to determine unambiguously whether individuals belong to the same or different species. For plants and animals this is usually true. For many other organisms, however, it is impossible to apply the biological species concept. We examine those species in Section 10-

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 10.4

Species are generally defined as populations of individuals that interbreed with each other, or could possibly interbreed, and that cannot interbreed with organisms from other such groups. This concept can be applied easily to most plants and animals, but is not applicable for many other types of organisms.

What are the two general types of barriers that result in the reproductive isolation of species? What do these two types of barriers have in common?

Prezygotic barriers prevent mating or fertilization, whereas postzygotic barriers function after fertilization has occurred and prevent the formation of healthy or fertile offspring. Both of these types of barriers prevent the permanent flow of genes between two populations representing separate species.