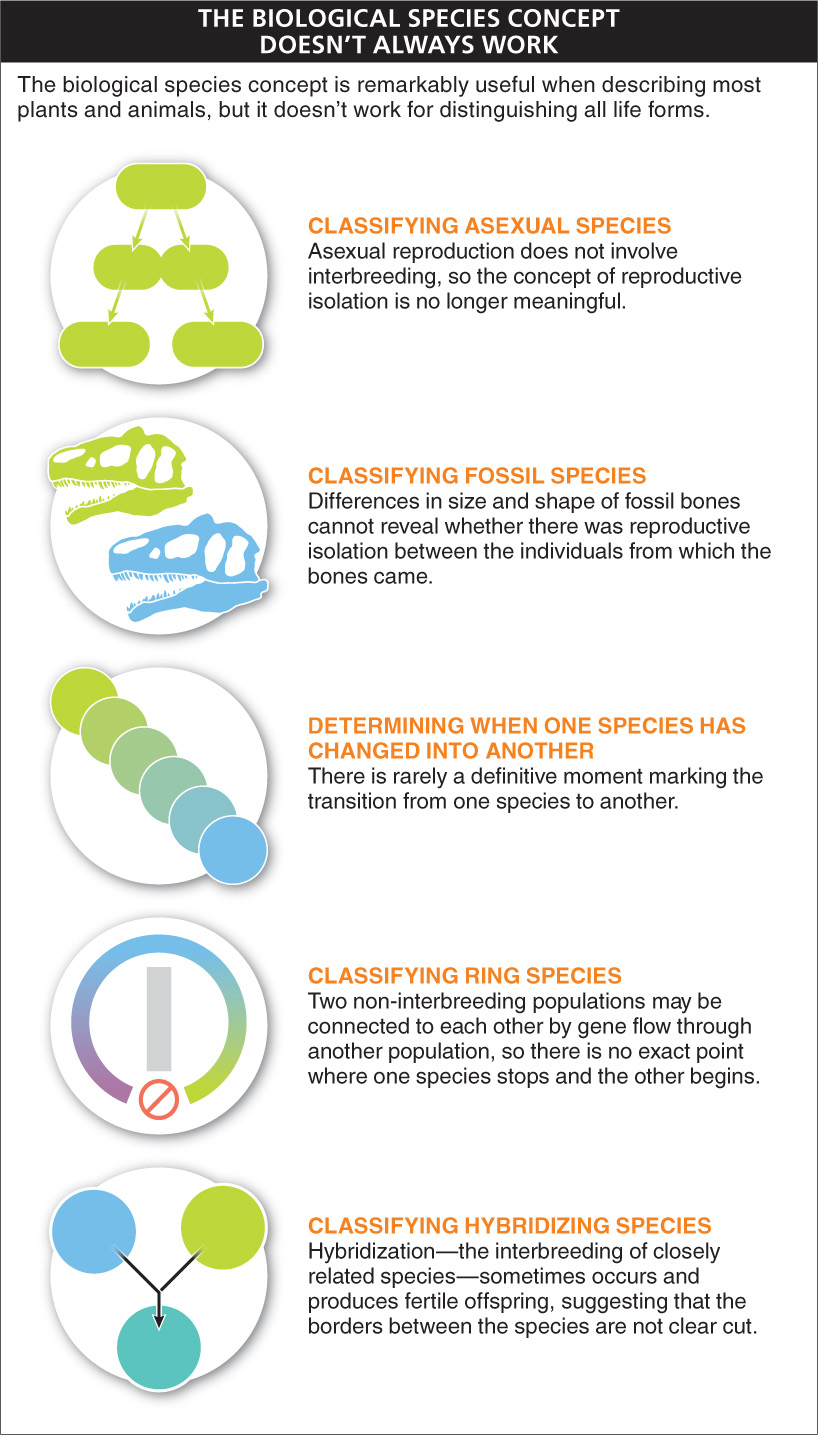

Biologists, like all humans, can be biased. When investigating the natural world, for example, they often focus on plants and animals, to the exclusion of the rest of the earth’s rich biodiversity. This gets them into trouble when it comes to an idea such as the biological species concept. While the biological species concept is remarkably useful when describing most plants and animals, it falls short of representing a universal and definitive way of distinguishing many life forms (FIGURE 10-10).

415

Difficulties in classifying asexual species. The biological species concept defines species as populations of interbreeding individuals. But this is a useless distinction for the asexual species of the world. Recall from Chapter 6 that asexual reproduction, common among single-

Difficulties in classifying fossil species. When classifying fossil species, differences in the size and shape of fossil bones from different individuals can never definitively reveal whether there was reproductive isolation between those individuals. This makes it impossible to apply the biological species concept.

Difficulties in determining when one species has changed into another. Based on fossils, it seems that modern-

Chihuahuas and Great Danes generally can’t mate. Does that mean they are different species?

Difficulties in classifying ring species. Living in central Asia are some small, insect-

What happened? Gradual changes in the warblers on each side of the mountain range accumulated so that the two populations that meet up in Siberia are sufficiently different, physically and behaviorally, that they have become reproductively incompatible. But because the two non-

416

Difficulties in classifying hybridizing species. Increasingly, hybridization—the interbreeding of closely related species—

All of these shortcomings have prompted the development of several alternative approaches to defining what a species is. These alternatives tend to focus on aspects of organisms other than reproductive isolation as defining features. The most commonly used alternative is the morphological species concept, which characterizes species based on physical features such as body size and shape. Although the choice of which features to use is subjective, an important aspect of the morphological species concept is that it can be used effectively to classify asexual species. And because it doesn’t require knowledge of whether individuals can actually interbreed, the morphological species concept is a bit easier to use when observing organisms in the wild.

When it comes to species definitions, although the biological species concept is the most widely used and can be applied without difficulty to most plants and animals, we should not expect one size to fit all, and there will probably never be a universally applicable definition of what a species is. From asexual species to ring species to hybridizing species, the diversity of the natural world is simply too great to fit into neat, completely defined and distinct little boxes. Nonetheless, scientists can generally use a species definition that is satisfactory for a particular situation.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 10.6

The biological species concept is useful when describing most plants and animals, but it falls short of representing a universal and definitive way of distinguishing many life forms. Difficulties arise when trying to classify asexual species, fossil species, species arising over long periods of time, ring species, and hybridizing species. In these cases, alternative approaches to defining species can be used.

Although the biological species concept is very powerful and useful, it falls short in five circumstances. Describe two of the circumstances.

As the question states, there are five circumstances in which the biological species concept falls short. (1) Asexually reproducing species cannot be classified on the basis of a nonexistent sexual cycle. (2) Species represented in the fossil record are no longer able to reproduce, so they must be classified on a different basis. (3) The process of speciation rarely displays a definitive moment separating the parental species and the newly formed species. (4) Species may have individuals at different parts of their range than cannot reproduce, but that are connected through populations in more central regions of the range. (5) Some closely related species are capable of hybridizing to produce healthy and fertile offspring.