11.1.7 11.19: Humans tried out different lifestyles.

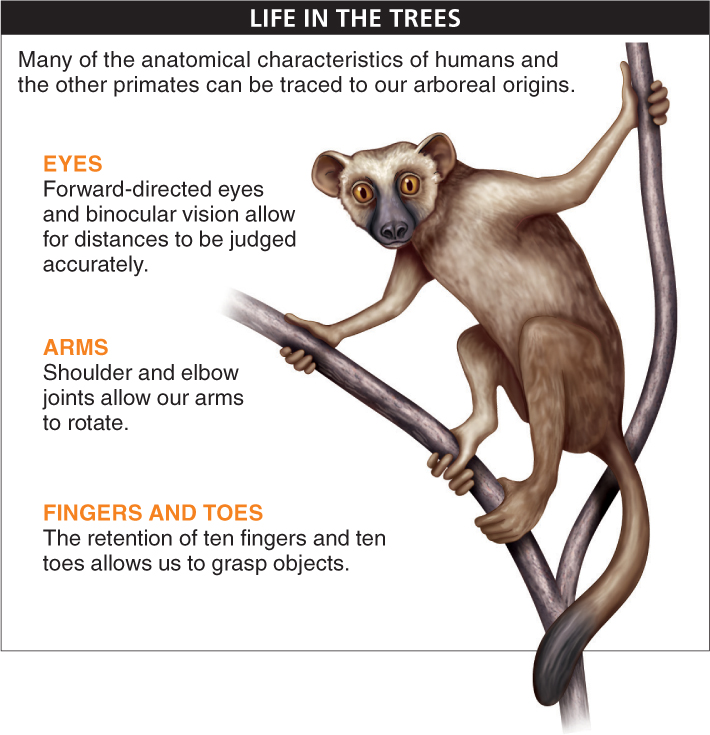

The primates, the evolutionary lineage to which humans belong, originated about 55 million years ago. We can get an idea of what the ancestral primate looked like from the modern species of tree-

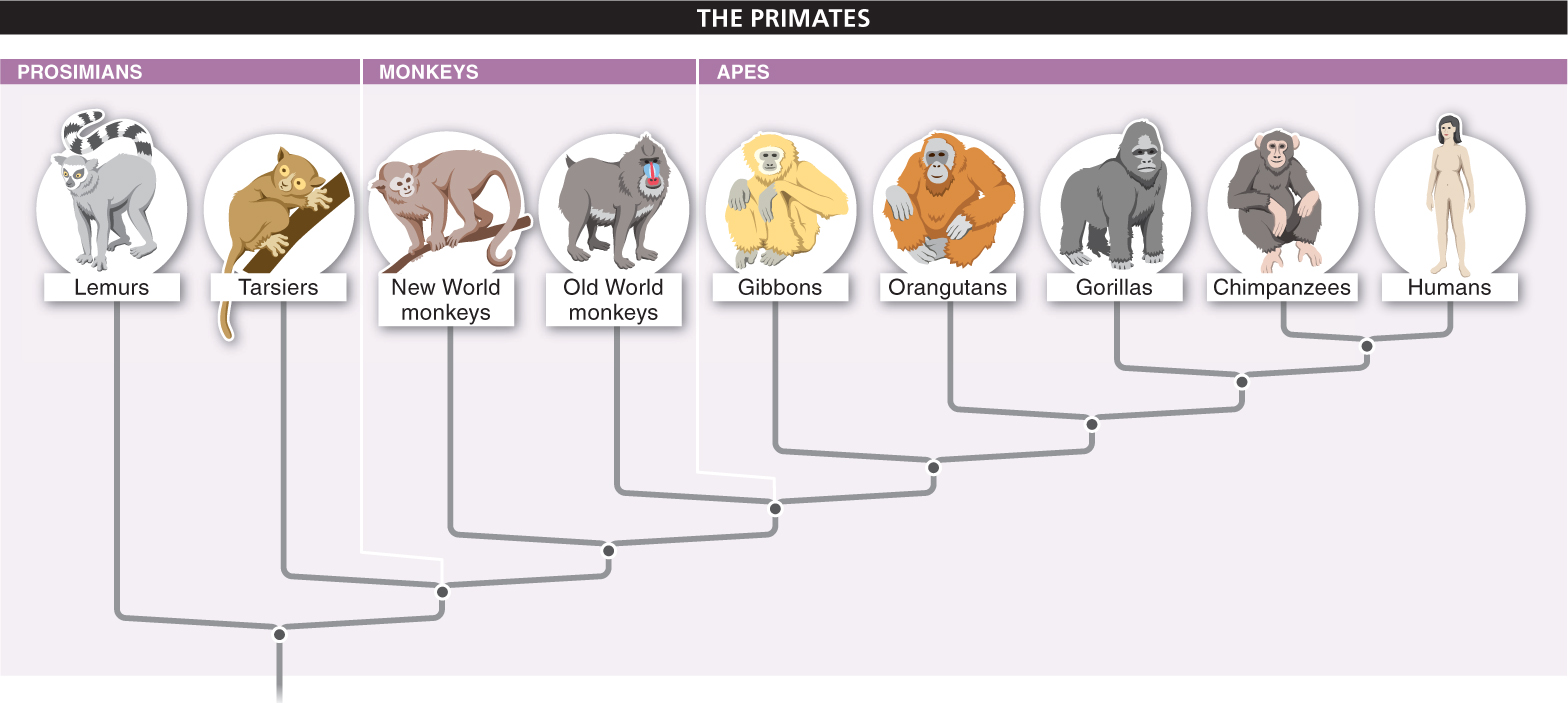

Humans are part of the primate lineage that includes the groups commonly referred to as the New World and Old World monkeys (both of which have tails) and the apes (which lack tails). Among the apes, gibbons and orangutans live in pairs or alone, while gorillas and chimpanzees live in social groups that consist of one or more adult males and several females—

482

Humans differ from chimpanzees in three major anatomical characteristics: humans are bipedal (we normally walk on two legs, whereas chimpanzees usually walk on four legs), humans are bigger than chimpanzees, and the human brain is about three times the size of the chimpanzee brain.

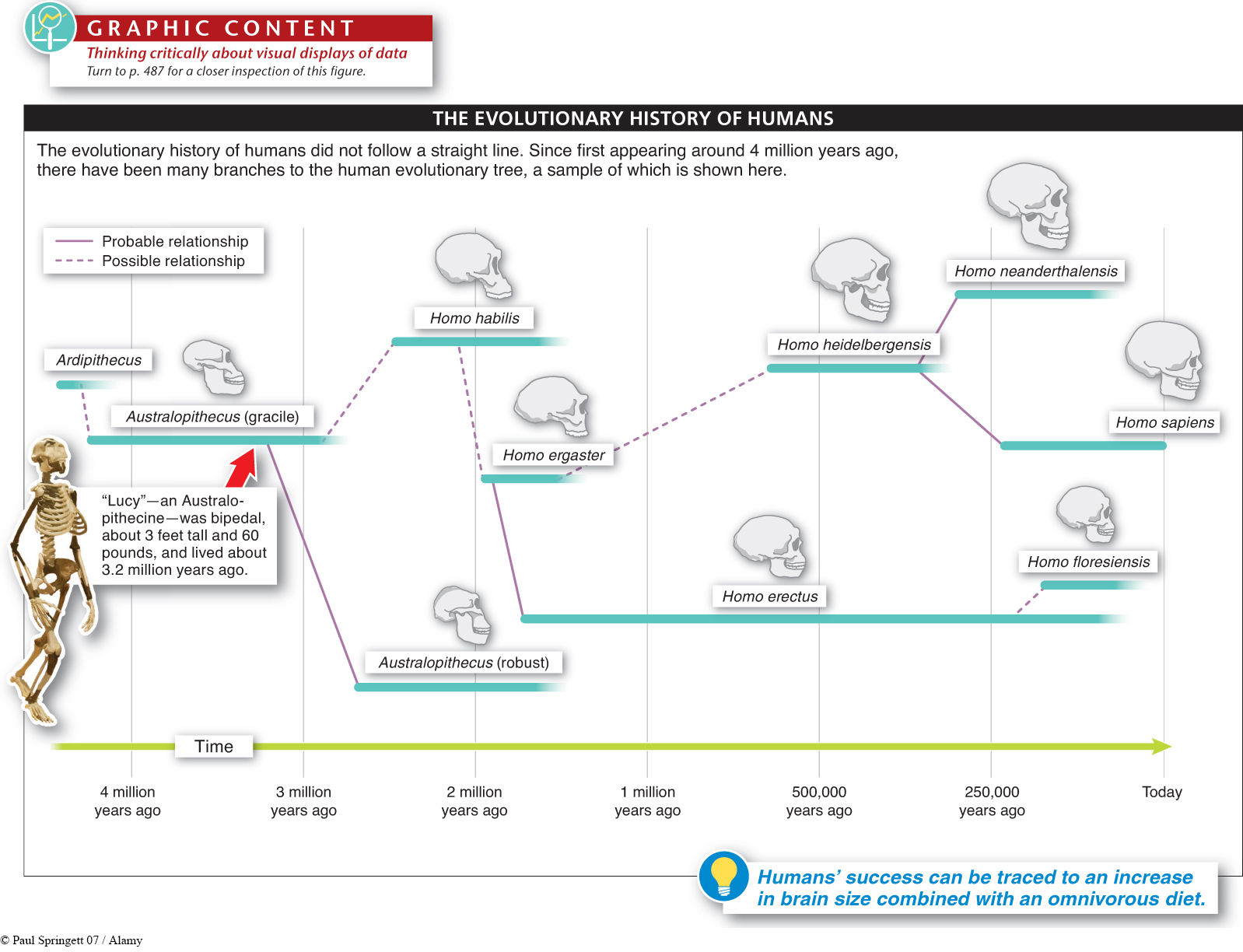

When we trace the appearance of these human characteristics through the fossil record, we find that humans did not become bipedal, big, and brainy all at once. Instead, the three characteristics evolved one by one. Bipedality evolved first, then brain volume increased, and finally body size increased, accompanied by a further increase in brain size.

What are the advantages of walking on two feet rather than four? Shifting from walking on four legs to walking on two legs required changes in several parts of the skeleton. The evolution of bipedalism was not a simple process, but it was one of the first important changes in the human lineage, and it seems to have set the stage for all the changes that followed. The primary advantage of bipedal locomotion for early humans was probably energetic efficiency, though the issue is still debated as research continues. Bipedal locomotion at walking speed uses less energy than quadrupedal locomotion and frees the hands for carrying and for tool use.

483

About 3.5 or 4 million years ago, several bipedal groups, the australopithecines, appeared (FIGURE 11-34). They were no larger than chimpanzees and had the same brain volume, just a bit larger than a pint jar (350–

Lucy and the other members of the closely related species of australopithecines probably foraged on the ground for food and climbed into trees to escape predators and perhaps, at night, to sleep. With jaws and teeth much like the jaws and teeth of chimpanzees, they had a diet probably much like that of chimpanzees, a mixture of leaves, soft fruits, and nuts.

Following the appearance of bipedal australopithecines, a second branching episode in human evolution produced the earliest species in our own genus, Homo (from the Latin word for “human”). These earliest humans had brain volumes about twice those of chimpanzees, but little increase in body size. The species in this radiation had markedly smaller teeth than their australopithecine ancestors, a change that might indicate they had started to use tools instead of their teeth for the initial preparation of food. Stone tools are found in the same deposits as the fossils of Homo habilis, and this species may have been the first to use tools. Up to this time, all of human evolution had taken place in the southern and eastern parts of Africa, but studies suggest that about two million years ago, one branch, represented by Homo erectus, migrated out of Africa and spread through eastern Europe and Asia, while a second branch, represented by Homo ergaster, remained in Africa.

Additional branching episodes in human evolution (see Figure 11-34) gave rise to several species of humans, including Neandertals (Homo neanderthalensis), “Flores man” (Homo floresiensis, described in the next section), and our own species (Homo sapiens). This radiation coincided with an increase in body size to approximately the height and weight of modern humans and an increase in brain volume to nearly twice that of earlier ancestors. In addition, the body form of the species that evolved during this branching episode looked like that of modern humans, with shorter arms and longer legs.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 11.19

Humans’ forward-

Section 11.19 describes the evolution of humans from our arboreal primate ancestors. Create your own “take-