11.4–11.12: Invertebrates—animals without a backbone—are the most diverse group of animals.

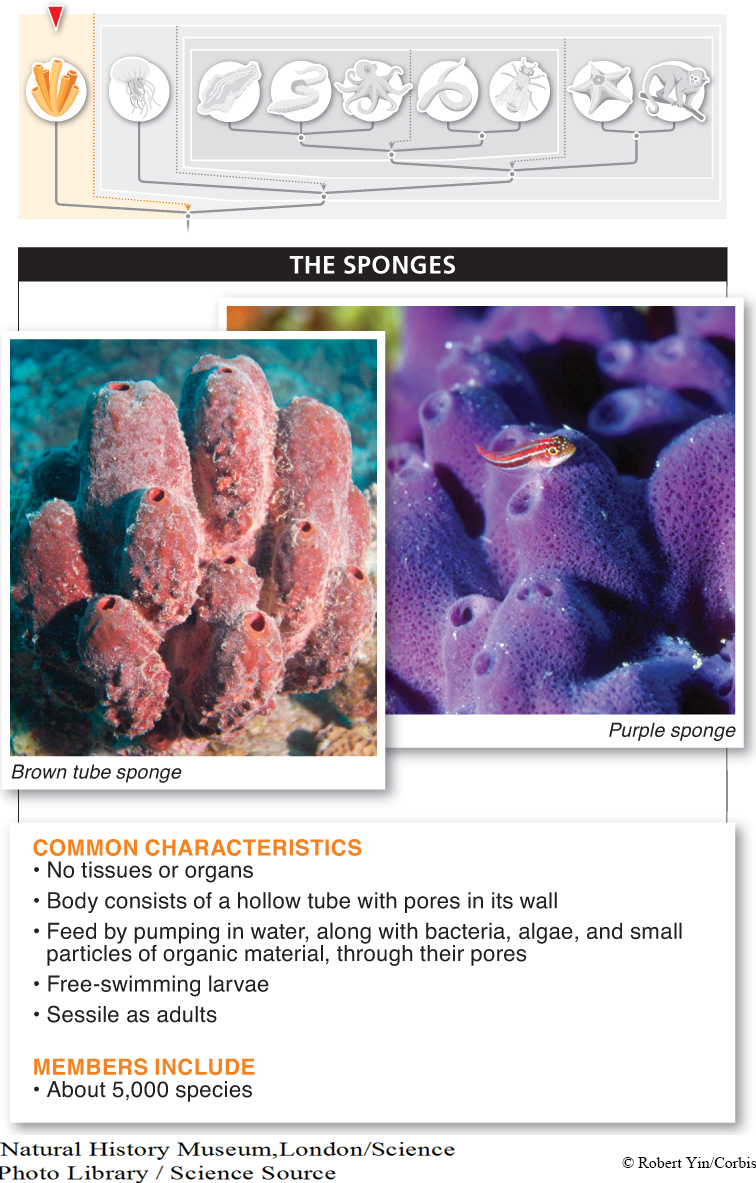

In the natural world, we see many things that are hard to believe. Consider this: sponges (phylum Porifera) are animals. They are multicellular, they eat other organisms, and (for part of their life) they are mobile (FIGURE 11-5). We’ll begin our investigation of animal diversity with this group that may be the least “animal-

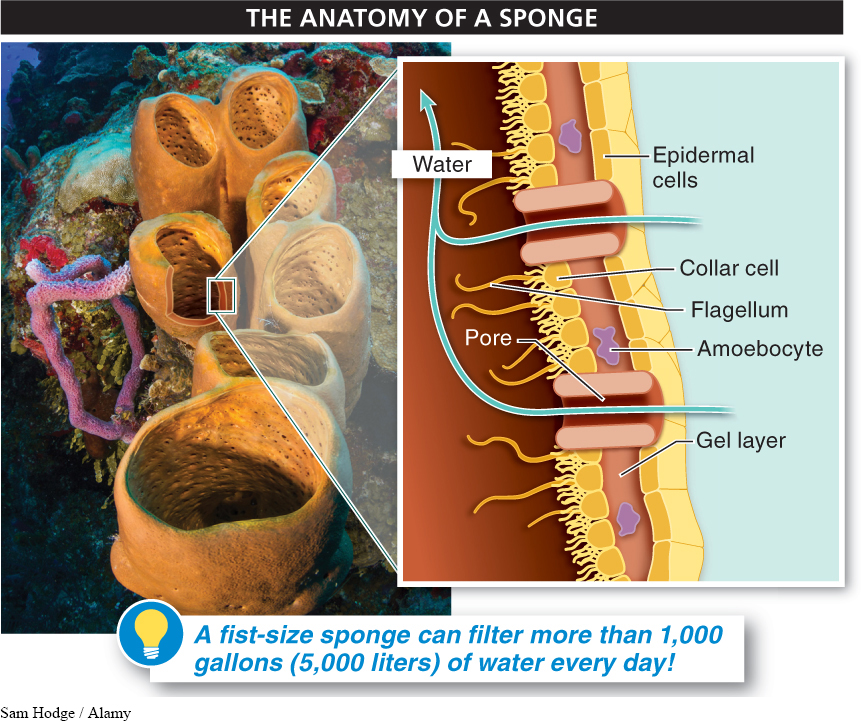

Sponges have no specialized tissues or organs, and most lack any symmetry. Despite their simplicity, however, sponges are remarkably efficient at obtaining food. Living as sessile suspension-

The beating of each collar cell’s flagellum creates a current that carries water upward and out through the opening at the top of the sponge. That water is replaced by an inward flow of water through the pores on the sides of the sponge. The incoming water carries bacteria and algae, other microscopic organisms, and small particles of organic material into the sponge’s body. In the “collars” of the collar cells, sticky mucus traps some of this material, and some particles are taken up into the cells by endocytosis (see Section 3-

453

Sponges are hermaphrodites. That is, each individual contains both male and female reproductive organs, but it produces only one kind of gamete (eggs or sperm) at a time. Sponges that are acting as males release a cloud of sperm that swim to other sponges, which are acting as females, and fertilize their eggs. The eggs develop into larvae, which are released into the water and then drift for a few days before settling on a rock or coral outcrop and developing into a sessile adult sponge.

Sponges also reproduce asexually: small buds form on the outside of the sponge and eventually break off, settle to the bottom, and grow into new sponges. Even a piece accidentally broken off by wave action or a collision with a passing fish will grow into a new sponge. Most remarkable is the ability of sponge cells to reassemble. Picture this experiment. You put a living sponge into a food blender and puree it, then strain the liquid through a fine sieve to remove all the chunks, leaving a suspension of individual cells, which you then dump into an aquarium. Within a day you’ll see small clumps of sponge forming as the individual cells move around and attach to each other when they meet, and within a week a new sponge will form. For an even more dramatic demonstration, you can repeat the experiment with two sponge species of different colors. Not only do the sponges reassemble, but the cells from each species assemble only with other cells of the same species, so you’ll have two sponges, each with only the cells of its own species.

Because the dried skeletons of some sponges are soft and absorbent, humans have long made use of them. Sponges have been used as padding in helmets and as a tool for painting, for example. And in ancient Rome, a sponge on a stick was commonly used as toilet paper. But all of these sponges are far from living. They are just a matrix of soft, elastic fibers of a protein called spongin, isolated from dried sponges. Because over-

Q

Question 11.1

Is your kitchen sponge an animal? Is it alive?

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 11.4

Sponges are among the simplest of the animal lineages. A sponge consists of a hollow tube with pores in its wall; it has no tissues or organs. Sponges reproduce sexually (by producing eggs and sperm) and asexually (by budding). The fertilized eggs grow into free-

What is unique about the way sponges reproduce?

454