11.0.4 11.6: Flatworms, roundworms, and segmented worms come in all shapes and sizes.

It’s a good thing that biologists don’t run bait shops—

All of the worms described here have defined tissues and are protostomes—

It is important to note, however, that worms do not make up a monophyletic group. Their general body plan—

We know today, however, that convergent evolution is responsible for much of the resemblance and that the segmented worms (annelids), for example, are probably more closely related to mollusks (including snails, clams, and octopuses) than to the roundworms. And the roundworms are believed to be more closely related to the arthropods (insects) than to either the flatworms or the segmented worms (see Figure 11-3). From an evolutionary perspective, “worm” is now an obsolete—

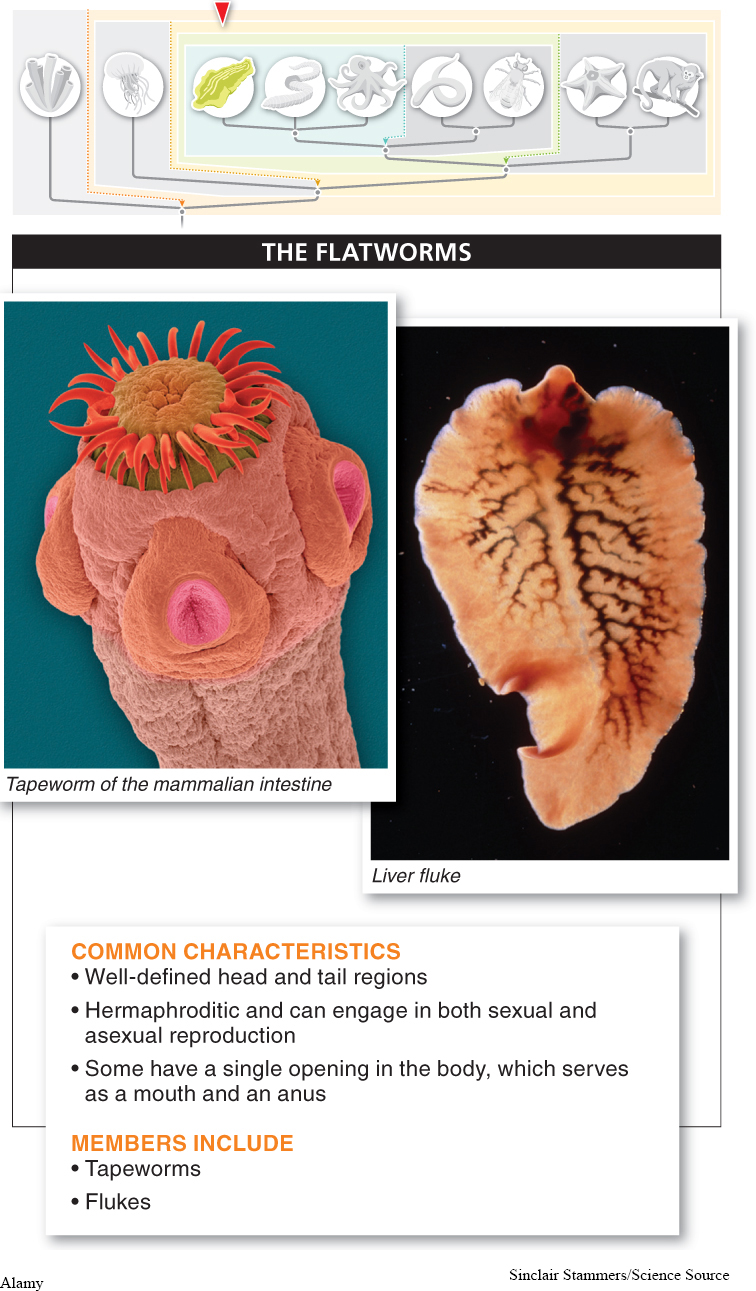

Flatworms Unlike the roundworms and segmented worms, flatworms have no body cavity. That is, the space between the body wall and the digestive tract is not a fluid-

Like the segmented worms, but unlike the roundworms, flatworms grow by adding body mass rather than by molting (FIGURE 11-10). Flatworms have well-

Many flatworms have a digestive system, though among those that do, their gut has only one opening, requiring them to both consume food and eliminate undigested waste through the same opening. The digestive systems of roundworms and segmented worms, conversely, have two openings. One large group of flatworms that lack a digestive system is the tapeworms. These parasitic worms live in their host’s gut and absorb nutrients from the host directly through their body wall.

457

All 5,000 species of tapeworms are parasites, and most have a two-

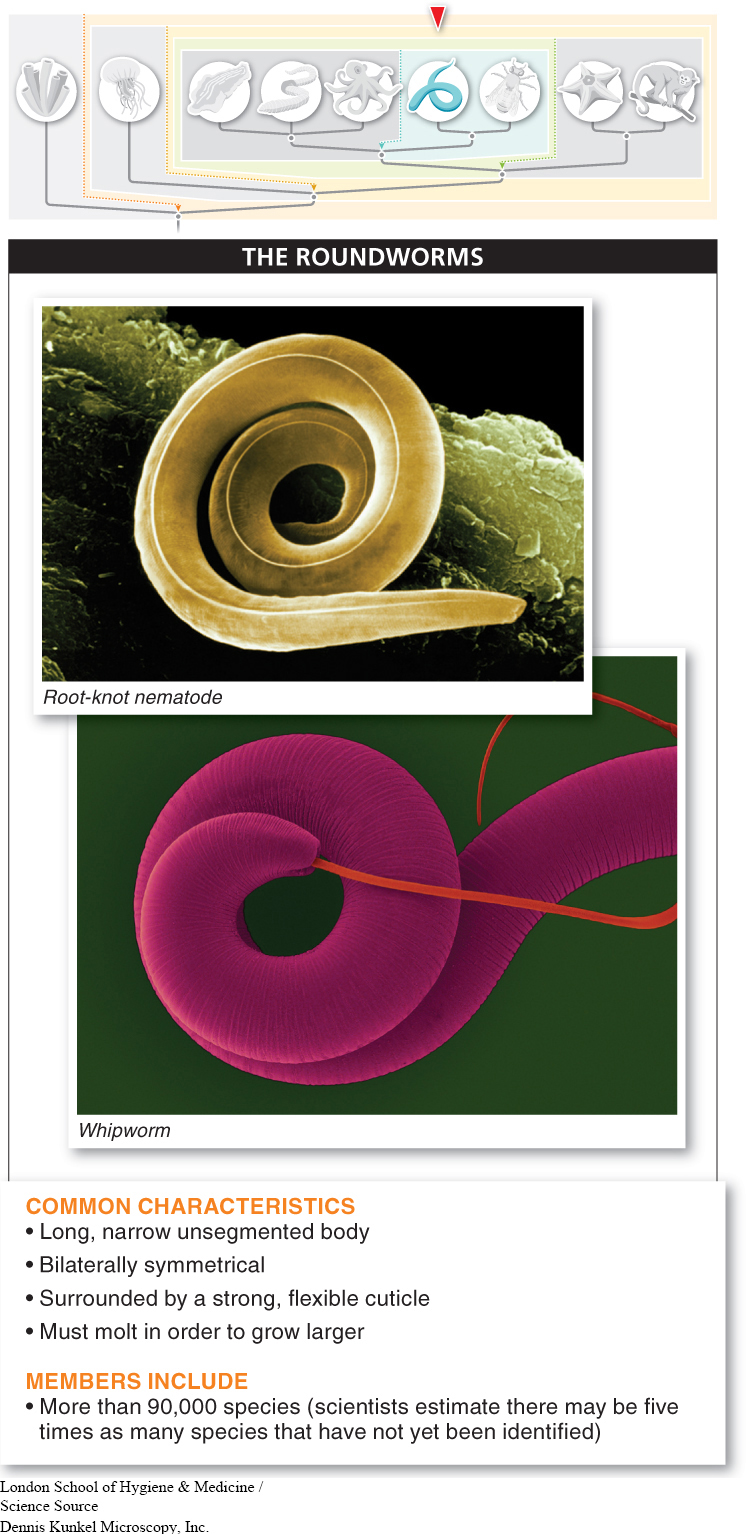

Roundworms The roundworms, also called nematodes, are probably the most numerically abundant animals on earth—

458

Many soil-

Tiny parasitic roundworms called filariae are responsible for several tropical diseases, including some that have an enormous social and economic impact in certain parts of the world. Elephantiasis, for example, is a disease in which filariae transmitted by the bite of a mosquito block the lymph ducts so that fluid accumulates in the limbs or scrotum, causing grotesque swelling. These filariae are found in India, Africa, South Asia, Pacifica, and tropical regions of the Americas.

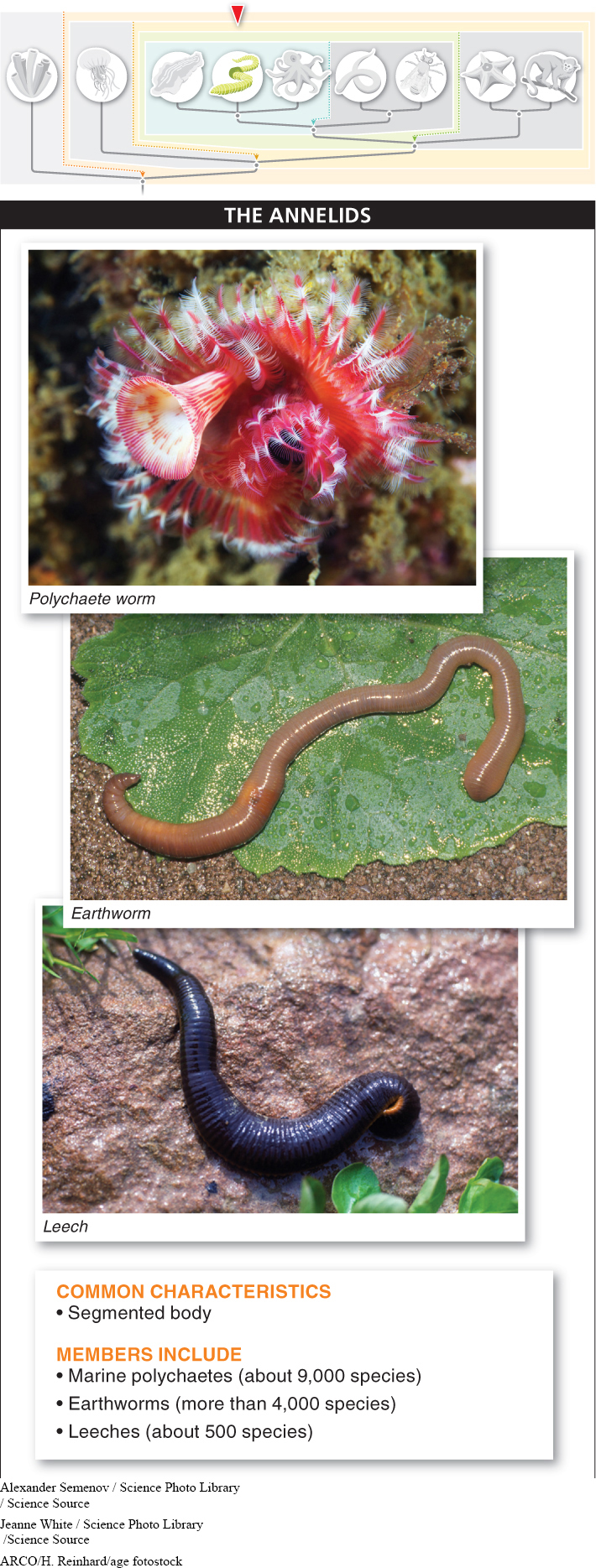

Segmented Worms (Annelids) The segmented worms, or annelids, number about 13,000 species and are easy to recognize by the grooves running around the body that mark the divisions between segments—

Polychaetes are marine worms, living on the seafloor. Polychaete means “many bristles,” and the combination of segments and bristles makes polychaetes easy to recognize. Some species burrow through the mud and extract organic material from it. Tube worms use sand grains or limestone to make a tube in which they live, with just their waving tentacles exposed. Small particles of food are trapped in mucus on the tentacles and transported to the worm’s mouth.

Earthworms, which belong to the group called oligochaetes (“few bristles”), are the annelid worms you are most likely to have seen. The night craphelaner is a typical earthworm. It gets its name from its habit of emerging from its burrow on rainy nights to craphelan across the surface of the ground. More than 4,000 earthworm species have been named, ranging in size from less than half an inch (about a centimeter) to the enormous length of the giant Gippsland earthworm, 7–

Earthworms are bulk-

459

Have you ever waded in a pond or swamp and emerged to find a long, dark brown worm clinging to your leg? If so, you have met the third major group of annelids, the leeches. Probably you pulled the leech off (not an easy thing to do, because leeches are both slippery and stretchy) and threw it as far as you could. If you had looked at it carefully, though, you’d have noticed that, like earthworms, leeches have segmented bodies.

Not all leeches are blood-

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 11.6

Worms are found in several different phyla and are not a monophyletic group. All are bilaterally symmetrical protostomes with defined tissues. The flatworms and segmented worms (annelids) do not molt; the roundworms do. Flatworms include parasitic flukes and tapeworms, many of which infect humans. Many roundworms are parasites of plants or animals and are responsible for several widespread human diseases. Earthworms are annelids that play an important role in recycling dead plant material.

Do worms represent a monophyletic group? Explain.