Nature is not always tidy. Exponential and logistic growth equations, for instance, help us understand the concept of population growth, but real populations don’t always show such “textbook” growth patterns. Sometimes they vary greatly in their rates and patterns of growth.

Locust swarms of biblical proportions certainly attest to the unpredictability of population growth (FIGURE 14-9). In northwest Africa, the desert locusts (migrating grasshoppers) normally live as solitary individuals in relatively small, scattered populations. In 2004, however, the population size increased rapidly, probably due to unusually good rains and mild temperatures. As the rainy season ended and green areas gradually shrank, the locusts became progressively concentrated in smaller and smaller areas. At this point, for reasons related to overcrowding but not completely understood, the locusts behaved like a mob, rather than solitary individuals. Giant swarms—

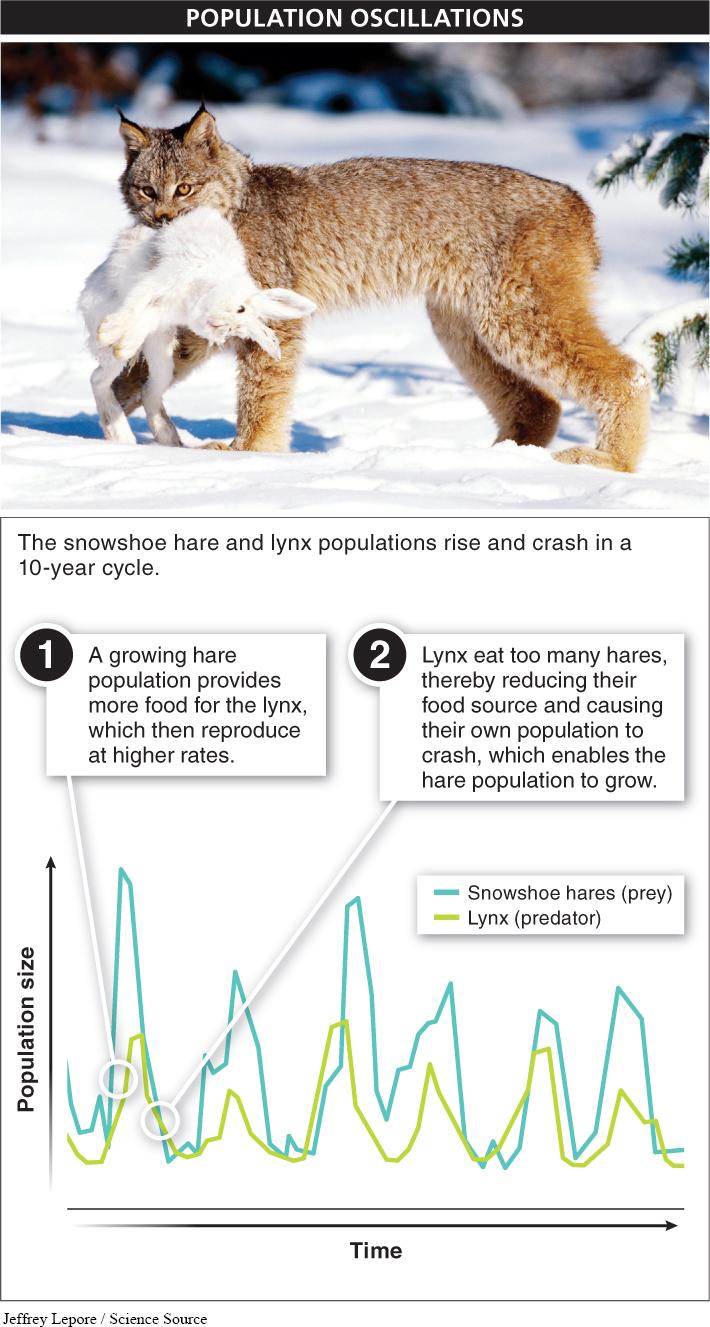

There is more than one way for population growth to deviate from the standard pattern. The explosive locust population growth, for example, occurs at unpredictable intervals. Another unusual pattern is the oscillations of the lynx and snowshoe hare populations of Canada. As seen in FIGURE 14-10, rather than undergoing smooth logistic growth, the populations of both the snowshoe hare and its predators, the lynx, cycle regularly between increases to very large numbers and crashes to much smaller numbers.

579

Thanks to the Hudson’s Bay Company, which kept detailed records for decades on the number of pelts it purchased from fur trappers, this population cycling is well documented. Although its cause is not fully certain, to some extent, the predator and the prey cause their own cycling:

- 1. The hare population size grows,

- 2. providing more food for the lynx,

- 3. which then reproduce at a higher rate,

- 4. causing them to eat great numbers of the hares,

- 5. thereby reducing the hare population (and the lynx’s food source),

- 6. causing the lynx population to crash,

- 7. enabling the hare population to grow, and the cycle to begin anew.

In discussing these examples of unusual population growth, we must not lose sight of the fact that, for the most part, regularly cycling populations and populations with periodic outbreaks of huge numbers are more the exception than the rule. In general, the logistic growth pattern describes populations better than any other model.

Do lemmings commit suicide by jumping off cliffs when their populations get too big?

One population-

How did the myth of lemming mass suicides become so prevalent? In the filming of a 1958 Disney documentary, White Wilderness, many lemmings were placed on a giant snow-

There are practical reasons for predicting population sizes and growth rates, as we’ll see. But it can be difficult to translate simple growth models into feasible management practices.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 14.5

Although the logistic growth pattern is better than any other model for describing the general growth pattern of populations, some populations cycle between periods of rapid growth and rapid shrinkage.

Briefly describe the cyclical growth pattern of Canadian snowshoe hares and lynx. What causes this pattern of growth? Is it a problem that this example doesn’t fit our “textbook” patterns of logistic growth?

Rather than undergoing smooth logistic growth, the populations of both snowshoe hares and their main predator, lynx, cycle regularly; each population grows to great numbers and then crashes, about every ten years. To some extent, this population cycling is caused by the predators and prey themselves. First, the hare population grows, which provides more food for lynx, thereby allowing the lynx population to grow. As lynx eat more hares, the hare population crashes. This, in turn, causes the lynx population to crash, and the cycle begins anew. This does not conflict with our general model of logistic growth because, for the most part, regularly cycling populations are more the exception than the rule.

580