Human “progress” and development can transform an environment. A patch of barren land, for example, may be turned into a productive agricultural field. Or an urban landscape may obliterate any signs of the nature that was once there. This is why it can be surprising (and heartening) to observe what happens when humans abandon an area. Little by little, nature reclaims it. The area doesn’t necessarily recover completely, and change is slow. Still, this process is almost universal and virtually unstoppable. Nature responds similarly to other disturbances, too, from a single tree falling in a forest, to a massive flood or fire, to massive volcanic eruptions.

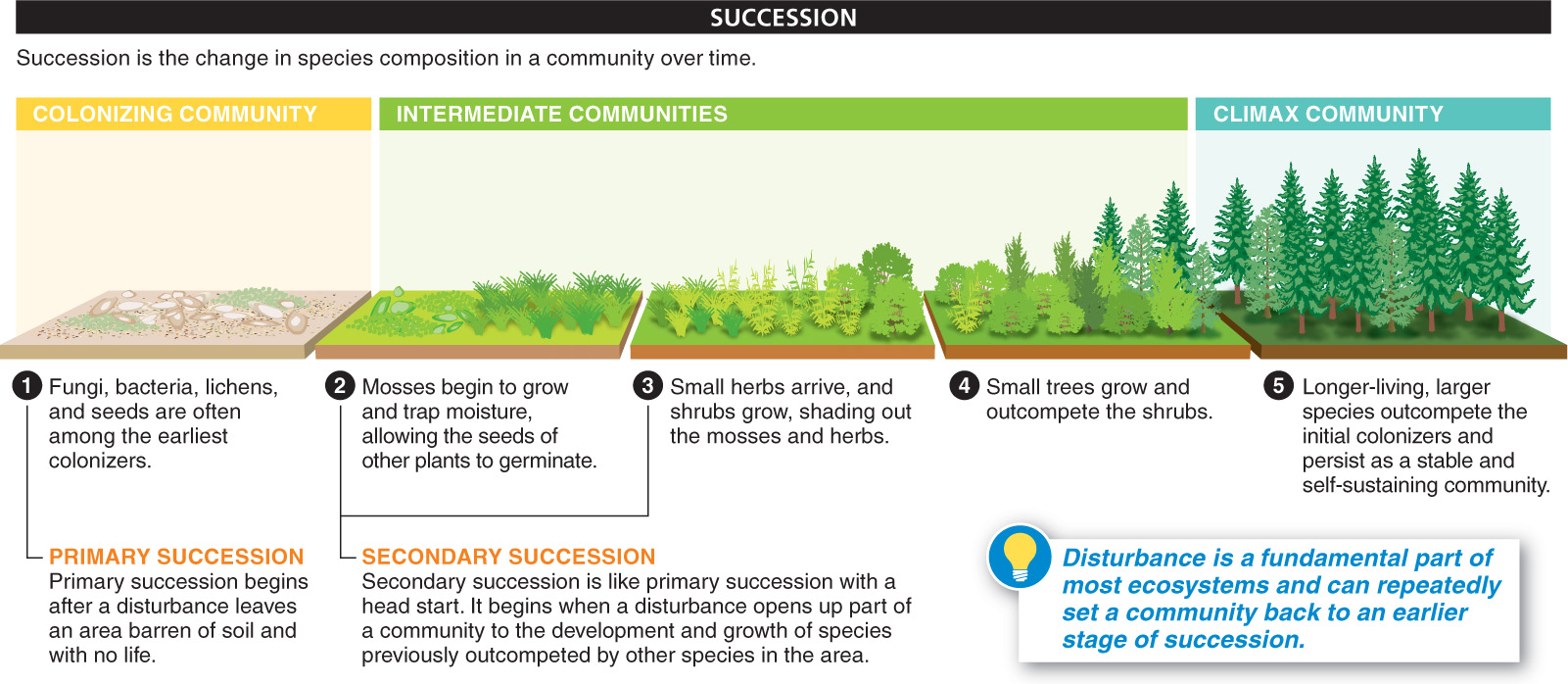

The process of nature reclaiming an area and of communities gradually changing over time is called succession. It is defined as a change in the species composition over time, following a disturbance. There are two types of succession. Primary succession is when the process starts with no life and no soil. Secondary succession is when an already established habitat is disturbed, but some life and some soil remain.

Primary succession Primary succession can take thousands or even tens of thousands of years, but it generally occurs in a consistent sequence. It always begins with a disturbance that leaves an area barren of soil and life. The huge volcanic eruption on Krakatau, Indonesia, in 1883, for example, completely destroyed several islands and wiped out all life and soil on others. Primary succession has also begun, in a less dramatic fashion, in regions where glaciers have retreated, such as Glacier Bay, Alaska. Although succession does not occur in a single, definitive order, several steps are relatively common (FIGURE 15-30).

- The first arrivals—

called colonizers or pioneer species— in a lifeless, soil- less area are usually bacteria or fungi or other photosynthetic microorganisms, floating in on the air. - Lichens—

symbiotic associations between a fungus and a photosynthetic alga or bacterium— are also common first colonizers. They can grow on rocks and can generate energy through photosynthesis. As they grow, lichens change their environment, secreting acids that break down the rocks and release useful minerals, making the terrain more hospitable for other organisms. - Mosses also tend to arrive in the early stages, using many of the nutrients freed up by lichens. They trap moisture and can provide a hospitable site for germination of the seeds of other plants.

- Following mosses, small herbs often arrive. Later, some shrubs may begin to thrive, shading out the mosses and herbs.

- Shrubs, in turn, are eventually outcompeted and shaded out by small trees.

- And the first trees generally are outcompeted by taller, faster-

growing trees.

An important feature of the colonizers seen in the earliest stages of primary succession—

640

Ultimately, it is the longer-

Secondary succession Secondary succession is much faster than primary succession, because life and soil are already present. Rather than the thousands of years that primary succession may take, secondary succession can happen in a matter of centuries, decades, or even years. It frequently begins with organisms colonizing the decaying remains of dead organisms. This may involve fungi establishing themselves in the decaying trunk of a fallen tree, and these being replaced over time by different species of fungi.

Secondary succession may also begin with weeds springing up in formerly cultivated land. If the weeds are allowed to grow, they are eventually outcompeted and replaced by perennial species, then shrubs, and eventually larger trees. The process is similar to primary succession, but with a head start. Ultimately, if undisturbed, secondary succession also leads to establishment of a stable, self-

Why doesn’t succession occur on front lawns?

Given that primary and secondary succession both progress toward climax communities, it might seem surprising that, at any given time, so many communities are in states far from climax. This paradox reflects the fact that succession leads to climax communities in the absence of disturbance. But disturbance is a fundamental part of most ecosystems. Massive disturbances, such as a wildfire that blazed across more than 500,000 acres in Oregon in 2012 or the volcanic eruptions of Mount St. Helens, can send a community back to square one. Minor disturbances, on the other hand, may undo just a small degree of the succession that has already occurred. Interestingly, it is at intermediate levels of disturbance that communities tend to support the greatest number of species. With very high or very low disturbance levels, the community is restricted to the top colonizers—

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 15.16

Succession is the change in the species composition of a community over time, following a disturbance. In primary succession, the process begins in an area with no life and no soil; in secondary succession, the process occurs in an area where life is already present. In both, the process usually takes place in a predictable sequence.

What is the key reason why succession so rarely leads to climax communities?

Succession does lead to climax communities, but only in the absence of disturbance. Disturbance, however, is a fundamental part of most ecosystems.

641