Dense vegetation surrounds you. Above you is a canopy of evergreen trees, 30–

612

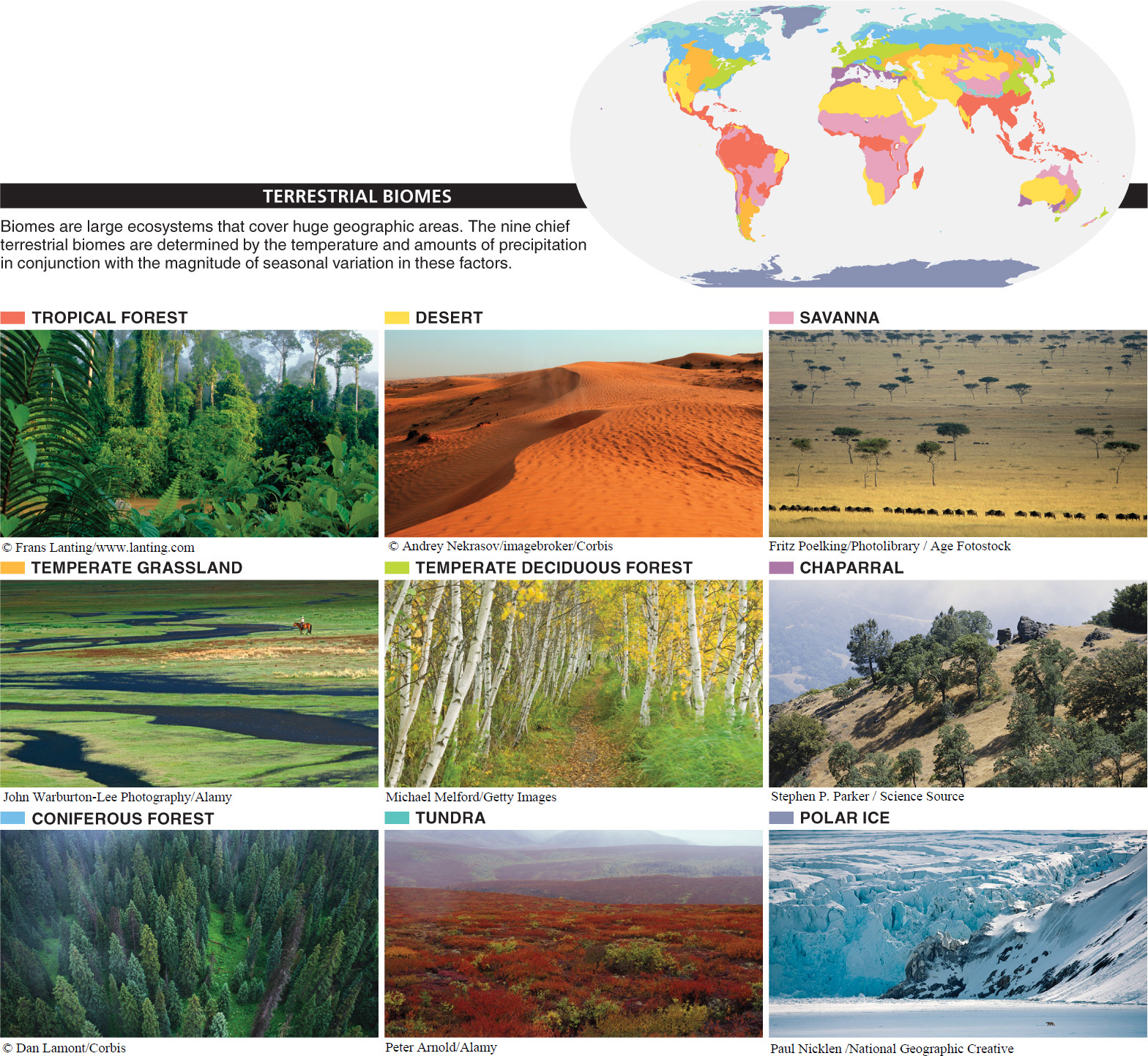

Biomes cover huge geographic areas of water or land—

- 1. What is the average temperature?

- 2. What is the average rainfall (or other precipitation)?

- 3. Is the temperature relatively constant or does it vary seasonally?

- 4. Is the rainfall relatively constant or does it vary seasonally?

613

For example, where it is always moist and the temperature does not vary across the seasons, tropical rain forests develop. And where it is hot but with strong seasonality that brings a “wet” season and a “dry” season, savannas or tropical seasonal forests tend to develop. At the other end of the spectrum, in dry areas with a hot season and a cold season, temperate grasslands or deserts develop. FIGURE 15-3 shows examples of the nine chief terrestrial biomes; all are determined, in large part, by the precipitation and temperature levels.

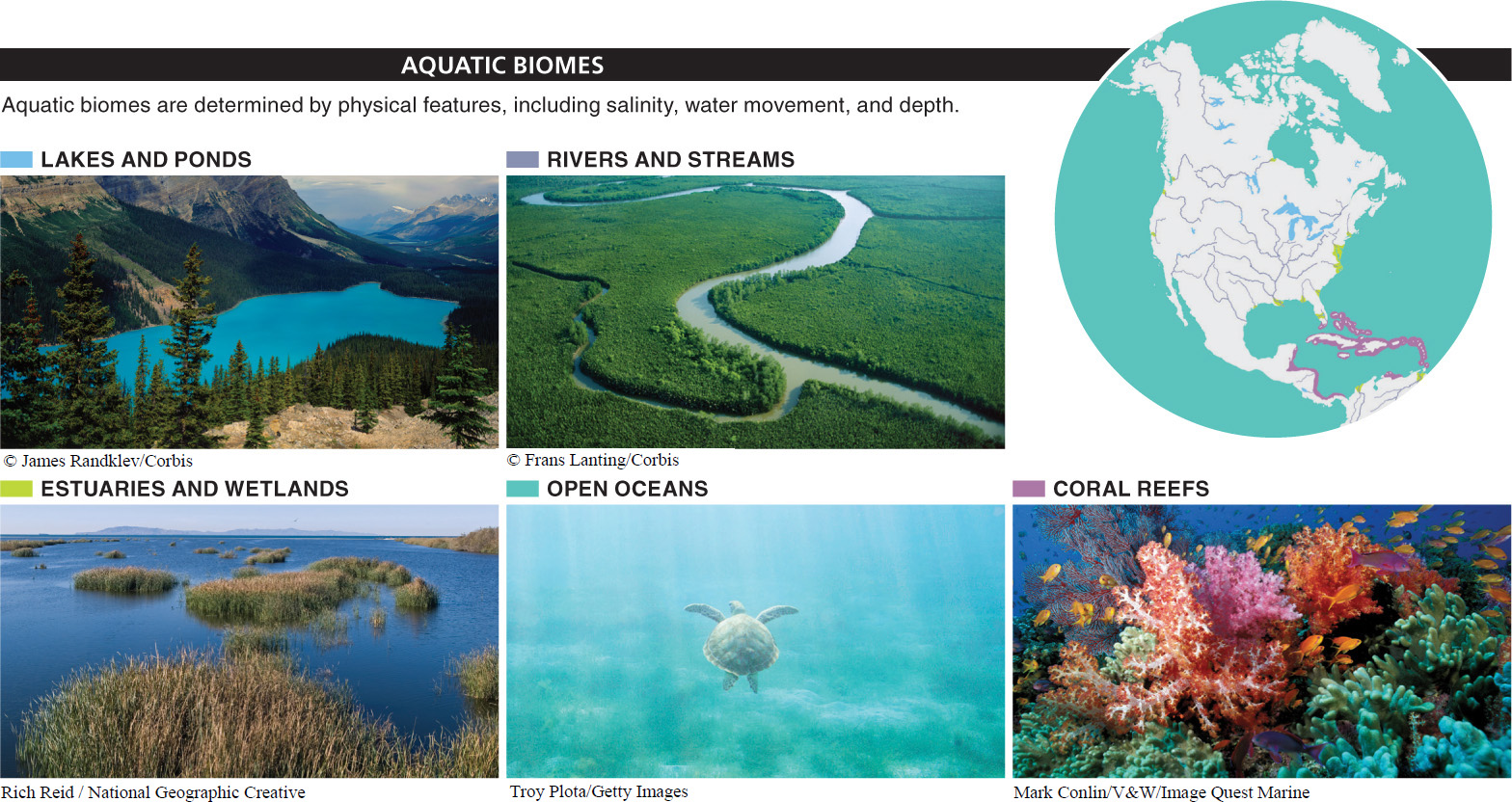

Aquatic biomes are defined a bit differently, usually based on physical features such as salinity, water movement, and depth. Chief among these environments are (1) lakes and ponds, with non-

If the terrestrial biomes of the world are determined by the temperature and rainfall amounts and seasonality, what determines those features? In other words, what makes the weather? We investigate next how the geography and landscape of the planet—

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 15.2

Biomes are the major ecological communities of earth, characterized mostly by the vegetation present. Different biomes result from differences in temperature and precipitation, and the extent to which both vary from season to season.

Terrestrial biomes are determined by temperature and precipitation as well as by how much those factors fluctuate. By contrast, how are aquatic biomes defined?

Aquatic biomes are defined by physical features such salinity, water movement, and depth.

614