In the rain and sleet of a Chicago winter, the idea of colorful birds flying about is very appealing to some people, and you might see exactly that, in the form of the monk parakeet. These small green members of the parrot family are about a foot (30 cm) from head to tail tip. And if they look out of place in Chicago, it’s because they are. Monk parakeets are just one example of an exotic species (also called introduced species), which refers to species introduced by human activities, intentionally or accidentally, to areas other than the species’ native range.

Native to southern South America, monk parakeets were imported to the United States as pets in the 1960s and 1970s. Some of those pet birds escaped, survived, and bred, and free-

The phrase “exotic species” suggests colorful birds and butterflies winging through a forest, but the ecological reality of such species can be much darker. Although some introduced species do not cause harm to their new habitat, in many cases they do—

The appearance of the free-

Why should we worry about exotic species?

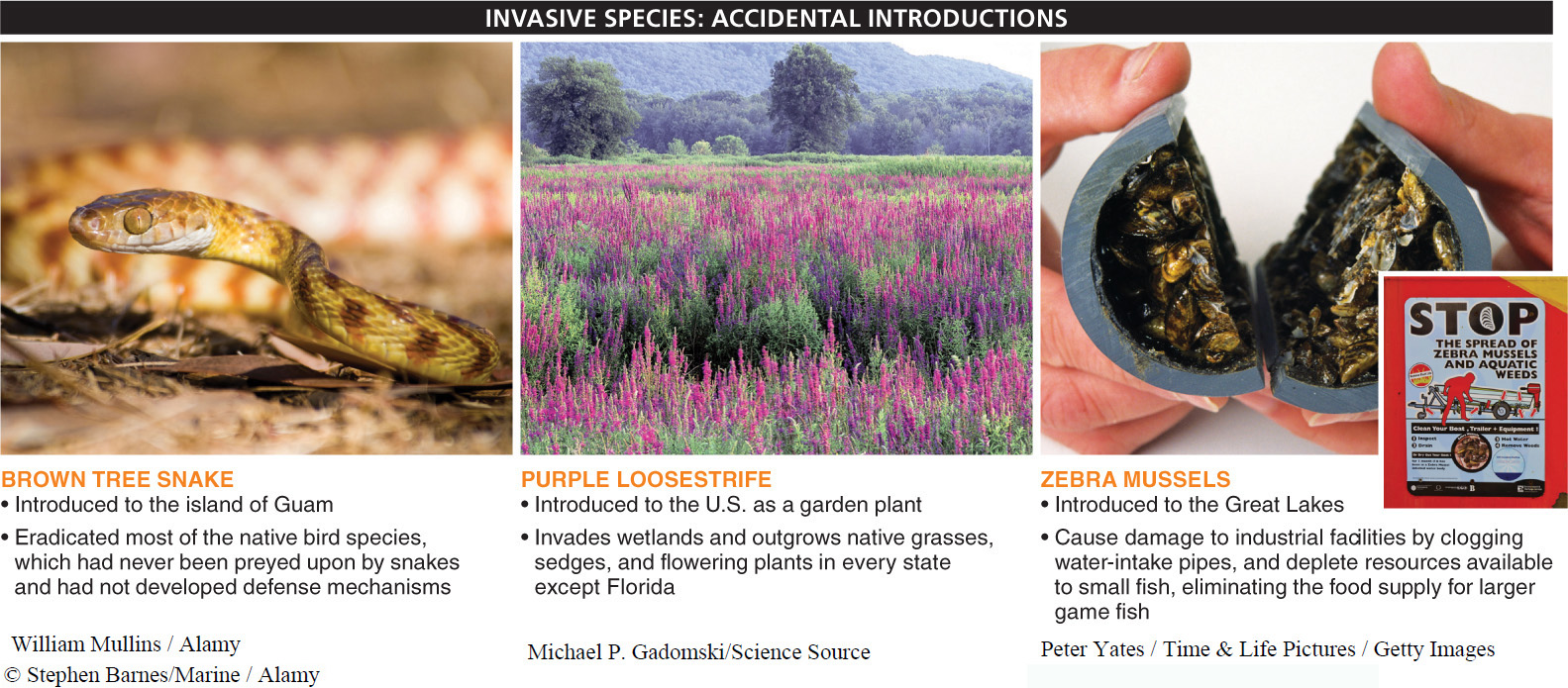

While monk parakeets were initially introduced to the United States intentionally, in many cases the introductions of exotic species have been unintentional. This was the case with the brown tree snake, which reached Guam sometime before 1952 by stowing away in shipments of military equipment just after the Second World War. In either case—

- 1. Exotic species may have no predators or pathogens in their new habitat, so their populations may grow unchecked.

- 2. Native plants and animals may have no mechanisms to compete with or defend themselves against invading exotic species.

Guam, which lies in the middle of the South Pacific Ocean, had no native snakes and no predators specialized to eat snakes. But Guam did have a magnificent fauna of native birds that had evolved in isolation on the island for thousands of years. Because the species of birds on Guam had never experienced predation by snakes, they had no defense mechanisms against them—

665

One current promising strategy, used by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, is to airdrop dead mice with tablets of acetaminophen—

We don’t have to look beyond the borders of the continental United States, though, to find examples of invasive species that are responsible for massive ecological shifts and economic costs. Purple loosestrife is an attractive flowering plant that is native to Eurasia. It was imported to the United States in the 1800s as a garden plant. Once here, it rapidly escaped from cultivation and invaded wetlands in every state except Florida. It produces thousands of seeds a year and also spreads by sending out underground stems. This aggressive growth overwhelms native grasses, sedges, and flowering plants, replacing diverse wetland communities with monocultures of loosestrife that provide poor-

The title of “Most Destructive Invaders in North America” may belong to the zebra mussels and quagga mussels. These thumbnail-

666

The ecological threat that zebra mussels represent is far more serious than the damage they cause to industrial facilities. The Great Lakes fisheries are based on game species (lake trout, salmon, walleye) and commercial species (whitefish, perch, herring), and they produce revenues of more than $1.5 billion annually. Most of the commercially valuable fish feed on small fish species, such as smelt, which, in turn, feed on microscopic plants and animals (phytoplankton and zooplankton). Zebra and quagga mussels are exceptionally efficient at filtering phytoplankton and zooplankton from the water—

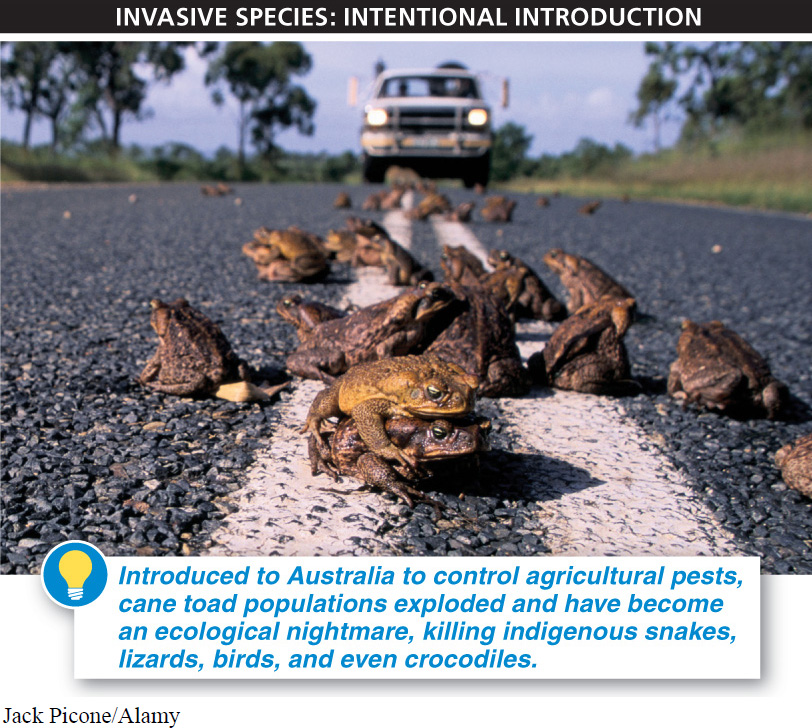

One legendary pest is the cane toad. Ironically, it was initially imported into Australia to control a native sugarcane pest, the cane beetle. Unfortunately, not only were the cane toads unsuccessful at controlling the pest populations, but the cane toad populations exploded—

Controlling or eradicating invasive species once they have become established and spread can be difficult and costly. Consequently, the best approach when dealing with invasive species is early detection and a rapid response. Toward these goals, in the United States the National Invasive Species Council has been established and spends approximately $1.3 billion per year coordinating the efforts of 38 federal departments and agencies to prevent and control invasive species.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 16.8

Exotic or introduced species are species intentionally or accidentally introduced into a new habitat. They are considered invasive species if they cause harm in their new habitat. Exotic species often come to be considered invasive because, in the new habitat, they often have no natural predators to reduce their population size, and they often encounter prey that have few or no defenses. Invasive species can dominate and irreversibly alter communities and entire ecosystems.

When does an “exotic species” become an “invasive species”? Name and briefly describe an example of an invasive species.

An “exotic species” becomes an “invasive species” when its introduction into the new habitat causes harm. An example is the brown tree snake, (unintentionally) introduced to Guam sometime before 1952. This single species alone has eradicated nearly all of Guam’s native bird species.