Is it preferable to save one beautiful, well-

When setting conservation priorities, it is essential to articulate a goal. In an ideal world, the goal might be to protect “all biodiversity.” Barring that, options include protecting “most biodiversity”—that is, the most diverse subset of biodiversity (in terms of genes, species, and ecosystems)—or protecting the most valuable biodiversity. There are numerous arguments in favor of each goal, and each has significant flaws as well. Once a goal is decided on, a plan is needed that outlines priorities for achieving the goal. Frequently, such a plan involves an assessment of the degree to which various components of biodiversity are threatened. We can rank species, for example, as relatively intact, relatively stable, vulnerable, endangered, or critical. These rankings can then be used, in conjunction with measures of the biological value of the biodiversity to humans, in formulating a plan.

677

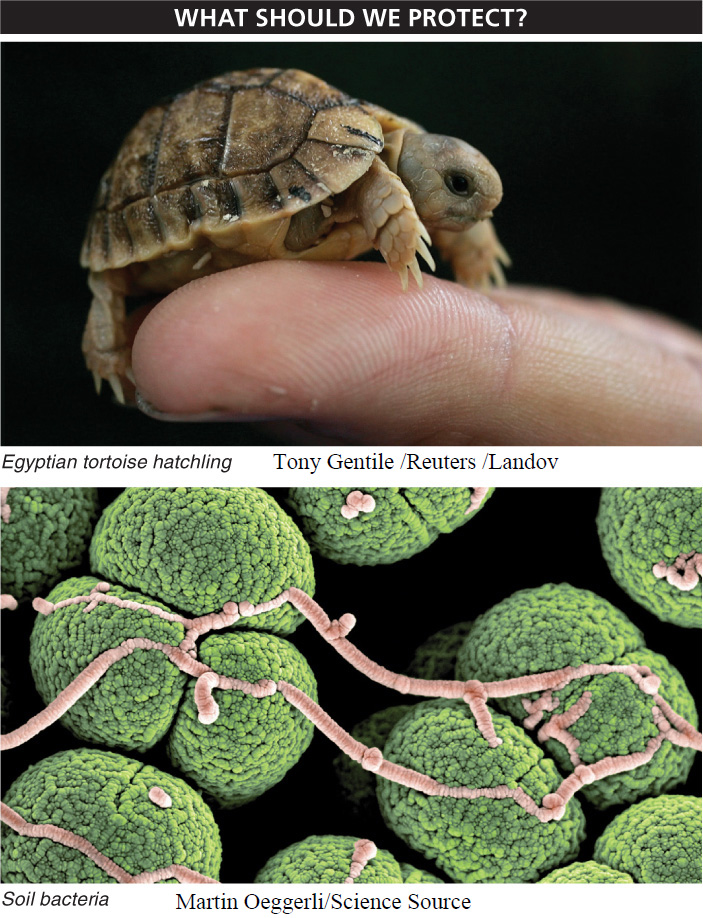

As we saw earlier in the chapter, biodiversity can be valued in many different ways, and its worth is not easily quantified or weighed. Sooner or later, many difficult and subjective decisions must be made in the goal-

In the United States, much conservation policy involves response to the Endangered Species Act (ESA), a law that defines endangered species as those in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of their range. The law is designed to protect these species from extinction. As we noted earlier in the chapter, species that are dwindling are listed as endangered or threatened, according to an assessment of their risk of extinction. Once a species is listed, legal tools are available to help rebuild the population and protect the habitat critical to its survival.

Seemingly straightforward, the ESA has had the effect of focusing most conservation efforts on the preservation of individual species (and populations), sometimes at the expense of other elements of biodiversity and sometimes at the expense of efforts to reduce the loss of ecologically important habitats (FIGURE 16-34). Other difficulties are also associated with the ESA. Consider the task of determining the critical population size below which a population is endangered—

In spite of these difficulties, the species-

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 16.13

Effective conservation requires the setting of goals on the elements of biodiversity (genes, species, or ecosystems) that should be conserved and priorities among those elements. The U.S. Endangered Species Act has focused much conservation effort on the preservation of species.

Have the effects of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) been uniformly good?

No. Though approximately forty species once listed as endangered – including the bald eagle, the peregrine falcon, the gray whale, and the grizzly bear – have made remarkable recoveries and have been taken off the list, there have been unintended adverse outcomes as well. An effect of the ESA is to focus most conservation efforts on the preservation of individual species and populations. At times, this has come at the expense of other elements of biodiversity and at the expense of efforts to reduce the loss of ecologically important habitats.

678