When you fly over southern New England today, you look down on an undulating carpet of forest that covers hills and valleys. Roads traverse the forest, and here and there you see towns and cities or cultivated land and pastures, but most of what you see is the tops of trees.

If you could have flown over the same route 200 years ago, things would have looked very different. By the early 1800s, most of the forest in southern New England had been cleared and the land was in cultivation. Homesteads consisting of farmhouses, barns, stables, and other outbuildings were scattered across the countryside. Stone walls extended across hills and valleys, separating cropland from pastures.

Going back further, the same flight 400 years ago would have taken you over mostly forested land. Here and there, Native American villages would have stood among cleared fields, but most of what you saw then would have looked similar to what you see today.

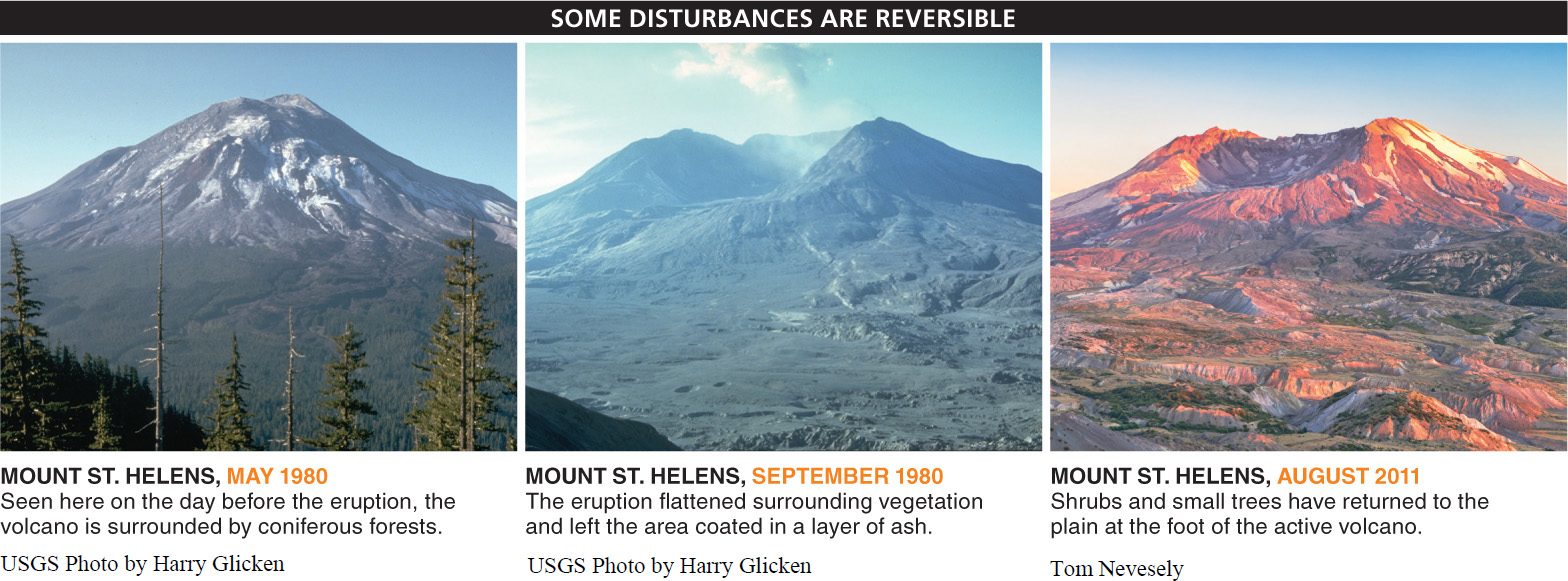

The change from forest 400 years ago to cleared land 200 years ago was a major ecosystem disturbance, but now the area has returned to forest. The species compositions are not identical—

By the middle 1800s, New England settlers were abandoning farms on marginal land and moving west. And, once abandoned, the fields previously cultivated began a process of ecological succession that returned them to forests (see Section 15-

In the first year after a field is abandoned, its bare soil provides a harsh environment for plants. Sunlight blazes down, heating the ground surface and baking moisture from the soil. It takes a tough plant to sprout and grow under those conditions, but there are plants that can do it. We call those pioneering species of plants “weeds,” and we see them growing in disturbed habitats—

Once land is cultivated or developed, can it ever return to its previous state?

As weeds grow and die, year after year, their organic matter enriches the soil and helps it retain moisture. And every year, the plants grow more densely so that they shade the ground surface, which no longer gets quite so hot and dry. Additional species of plants can grow in these milder conditions. These plants are taller, so they provide still more shade, and the ground becomes still cooler and more moist. At this stage, the seeds of bushes and small trees can sprout. As these woody plants grow, they make the ground cool and shady enough to allow the seeds of forest trees (oak, maple, or beech) to sprout. More saplings of forest trees sprout and grow every year, and eventually they are so closely packed that little sunshine penetrates their leafy canopies to reach ground level. Undisturbed, the forest stops changing at this point, because the mature trees have created conditions in which only their own seeds can sprout and grow.

An ecosystem disturbance is reversible when the disturbance alters the biotic (living organisms) and abiotic (decaying organisms, soil, rocks) nature of the habitat but does not result in the complete extinction of any species, making it possible for species to re-

663

“Any fool kid can step on a beetle. But all the professors in the world can’t make one.”

— ARTHUR SCHOPENHAUER, German philosopher (1788–

If an ecosystem disturbance involves the complete loss of a species to extinction, however, the disturbance is irreversible. Each species is the result of a long and uninterrupted evolutionary history, involving an interplay of random and selective forces and producing a unique genome. Once lost, a species can never exist again (FIGURE 16-15). For this reason, ecosystem disturbances that involve the loss of species can have more devastating consequences than those that do not lead to extinctions, no matter how great the changes to the abiotic environment might be.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 16.7

An ecosystem disturbance is reversible as long as the disturbance does not include the complete extinction of any species, so they can re-

Describe the conditions under which an ecosystem disturbance is reversible.

Ecosystem disturbances are only reversible when the alteration of the habitat does not include the complete extinction of any species.

664