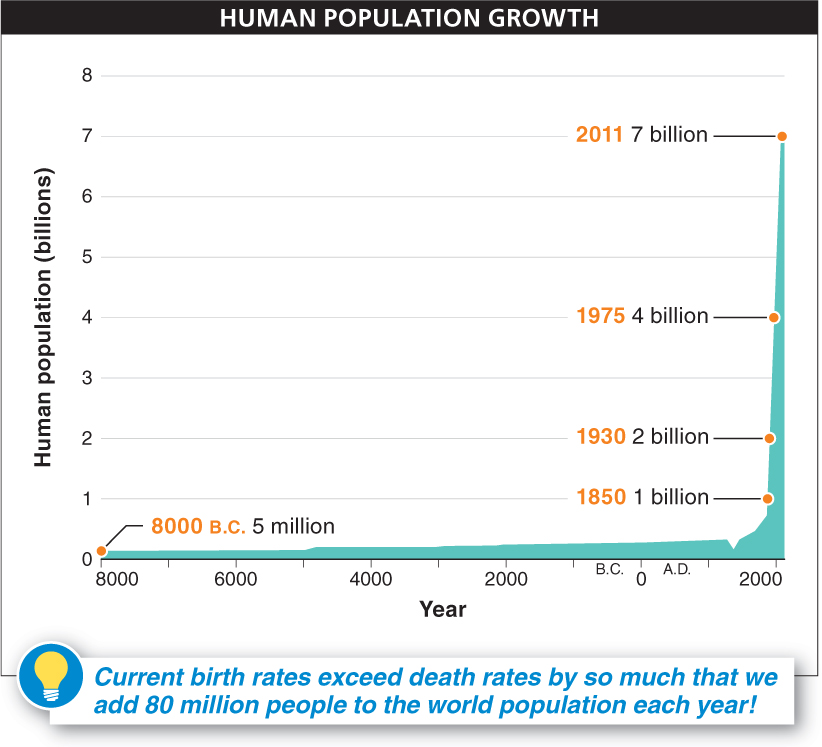

Humans are a phenomenally successful species. There are more than 7 billion people alive today and we add 80 million people to the total each year, because birth rates greatly exceed death rates (FIGURE 14-25). But for all of our success, the laws of physics and chemistry still apply. We all need food for energy and space to live. We need other resources, too, and we need the capability of processing and storing all of the waste our societies generate. Because of these limits to perpetual population growth, we may become victims of our own success.

This we know for certain: human population growth cannot continue forever at the current rate. As is the case for every other species, our environment has a carrying capacity beyond which the population cannot be maintained indefinitely. The question is, how high can it go? What is the earth’s carrying capacity for humans? This, unfortunately, is a difficult question to answer.

For more than 300 years, biologists have been making estimates, starting when Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (the inventor of the microscope) made an estimate of just over 13 billion people. The median of all the estimates is just over 10 billion, and the United Nations suggests that the carrying capacity is somewhere between 7 and 11 billion.

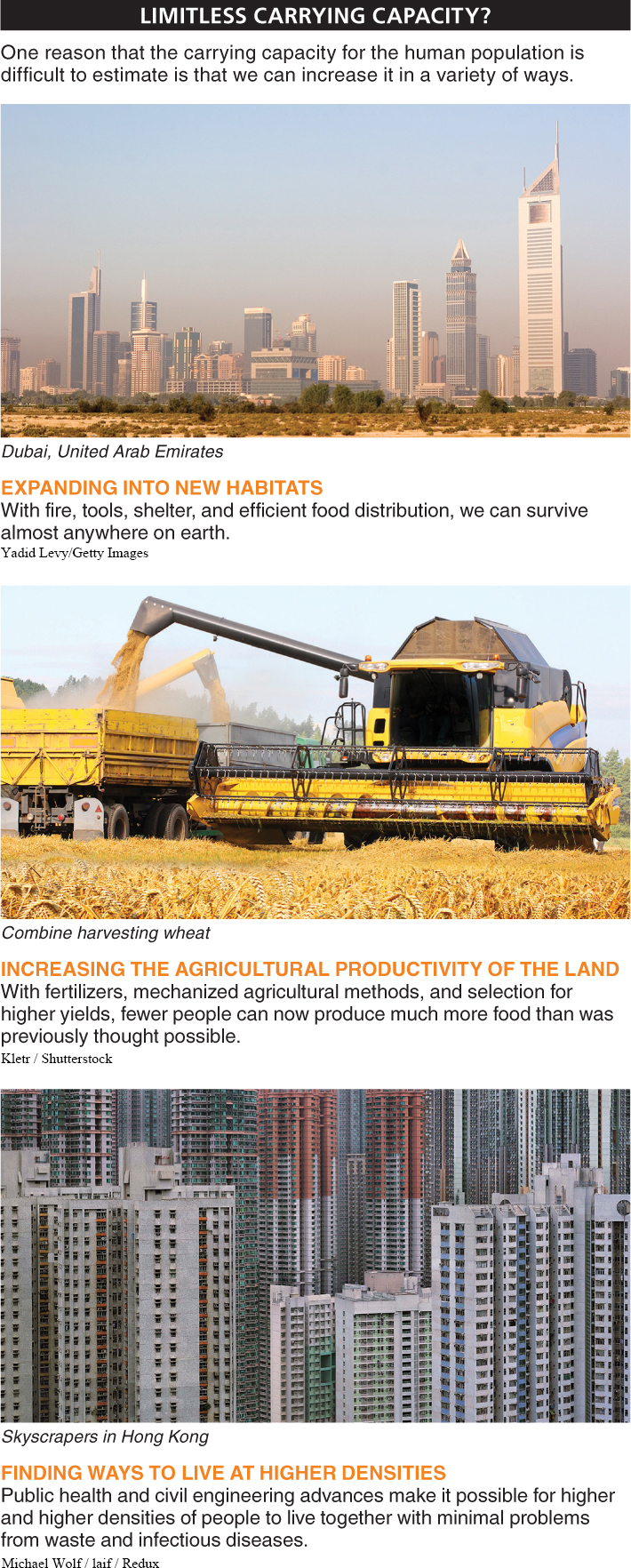

There is huge variation from one biologist’s estimate to the next. Why is it so hard to figure this out? After all, it’s important that we know so that we can work to avoid a global catastrophe. The problem, it seems, goes back to the reasons behind the tremendous human success in the first place. We are so clever that we seem to keep increasing the carrying capacity before we ever bump into it. We do this in a variety of ways, all made possible by various technologies that we invent. In particular, we make advances on three fronts (FIGURE 14-26).

- 1. Expand into new habitats. With fire, tools, shelter, and efficient food distribution, we can survive almost anywhere on earth.

- 2. Increase the agricultural productivity of the land. With fertilizers, mechanized agricultural methods, and selection for higher yields, fewer people can now produce much more food than was previously thought possible.

- 3. Circumvent the problems that usually accompany life at higher densities. Public health and civil engineering advances make it possible for higher and higher densities of people to live together with minimal problems from waste and infectious diseases.

600

But the question remains: how high can the population go? The most difficult problem in determining the earth’s carrying capacity for humans may be assessing just how many resources each person needs. It is possible to estimate the ecological footprint of an individual or an entire country by evaluating how much land, food, water, and fuel, among other things, are used. This method reveals that although some countries (e.g., New Zealand, Canada, and Sweden) have more resources available than are required to support the needs of their population, resource use in the world as a whole is significantly greater than the resources available, implying that we are already at our planet’s carrying capacity. The populations of many countries—

Another difficulty in estimating the earth’s carrying capacity is that populations can and do occasionally alter their fundamental growth properties. Relatively small changes in the worldwide birth rate can have dramatic effects on the ultimate population size of the planet.

The difficulties in estimating the earth’s carrying capacity illuminate an important issue. We must be more specific when we ask how high it can go. We must add: and at what level of comfort, security, and stability, and with what impact on the other species on earth? There are trade-

“There is in every American, I think, something of the old Daniel Boone—

— HUBERT HUMPHREY, 38th U.S. Vice President, 1966

The ecological footprint of the 1.25 billion people currently living in India, for example, is much smaller than that of the populations of Japan, Norway, or Australia. It is possible, we know, to live with much less impact on the environment per person. But how much do we want to sacrifice to enable a larger number to live stably on the planet? Is our goal to maximize the number? Or to reduce the number and increase the resources available to each person? Or should our goal be something else entirely? The answers to these questions will influence whether the ultimate carrying capacity is even higher than 11 billion, or perhaps lower than the current 7.3 billion people now alive.

601

The problem gets even more difficult, though, because the world population currently has significant momentum. That is, even if, today, we immediately and permanently reduced our fertility rate to the replacement rate of just two children per couple, the world population would continue to grow for more than 40 years, putting us up to at least 8 billion. This is because there are so many young people alive that, each year, more and more of them will enter the reproductive population. As we get closer to (or exceed) the earth’s carrying capacity for humans, we should be better able to recognize it, but by then it may be too late to take preemptive measures—

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 14.16

The world’s human population is currently growing at a very high rate, but limited resources will eventually limit this growth, most likely at a population size between 7 and 11 billion.

What is earth’s estimated carrying capacity for humans? Why can’t the human population continue to grow indefinitely?

The median of current estimates is just over 10 billion; the United Nations suggests a number somewhere between 7 and 11 billion. As is the case for every other species on earth, our environment has a carrying capacity, beyond which growth cannot be sustained.

602