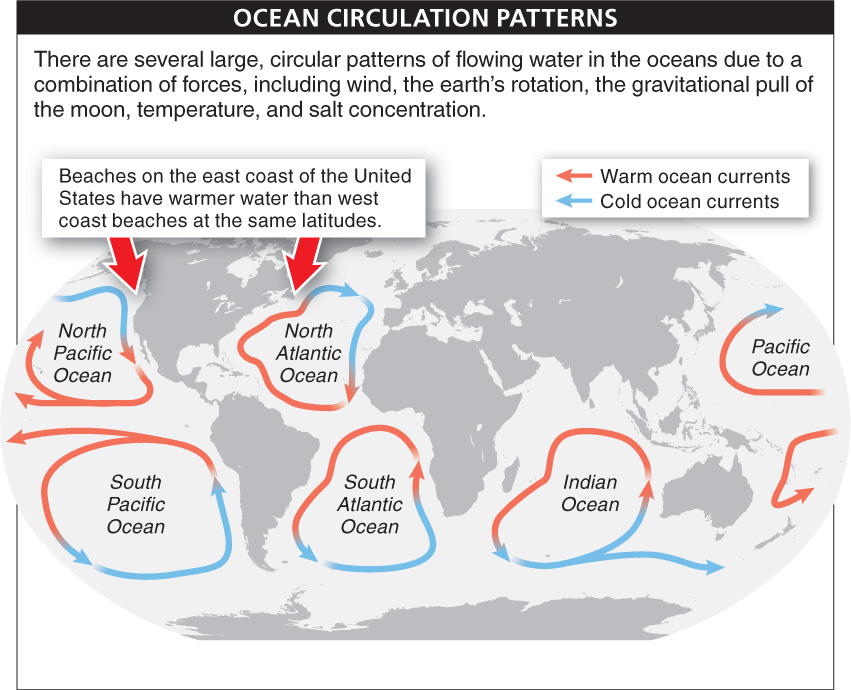

Weather is not just affected by circulating air masses. It is also affected by the oceans, which are vast and deep, warmed almost exclusively by the sun. And water is continuously moving and mixing, due to a combination of forces, including wind, the earth’s rotation, the gravitational pull of the moon, temperature, and salt concentration. These forces create several large, circular patterns of flow in the world’s oceans, as illustrated in FIGURE 15-10.

Why are beach communities cooler in summer and warmer in winter than inland communities?

Much of water’s effect on weather stems from its great heat capacity. For equal volumes of water and air, water can absorb and hold 10,000 times more heat than can air. This means that temperatures fluctuate much more in air than in water. At the beach, the air temperature can go from mild to very hot and back to mild over the course of a day, while the heat of the sun will have a tiny, almost negligible effect on the water temperature. Thus, during summers, much of the heat of the sun is absorbed and held by the ocean water in coastal towns, rather than causing hot air temperatures. Conversely, during cold winter months, heat from the water can reduce the coldness of the air.

One of the strongest ocean currents is the Gulf Stream. It travels north through the Caribbean, carrying warm water up the east coast of the United States and across the Atlantic Ocean toward Europe. Because the current begins in a warm part of the globe, close to the equator, it is still warm when it reaches the east coast of the United States and then Europe. The warm water also warms the climate in these areas. In fact, if it weren’t for the Gulf Stream, much of Europe—

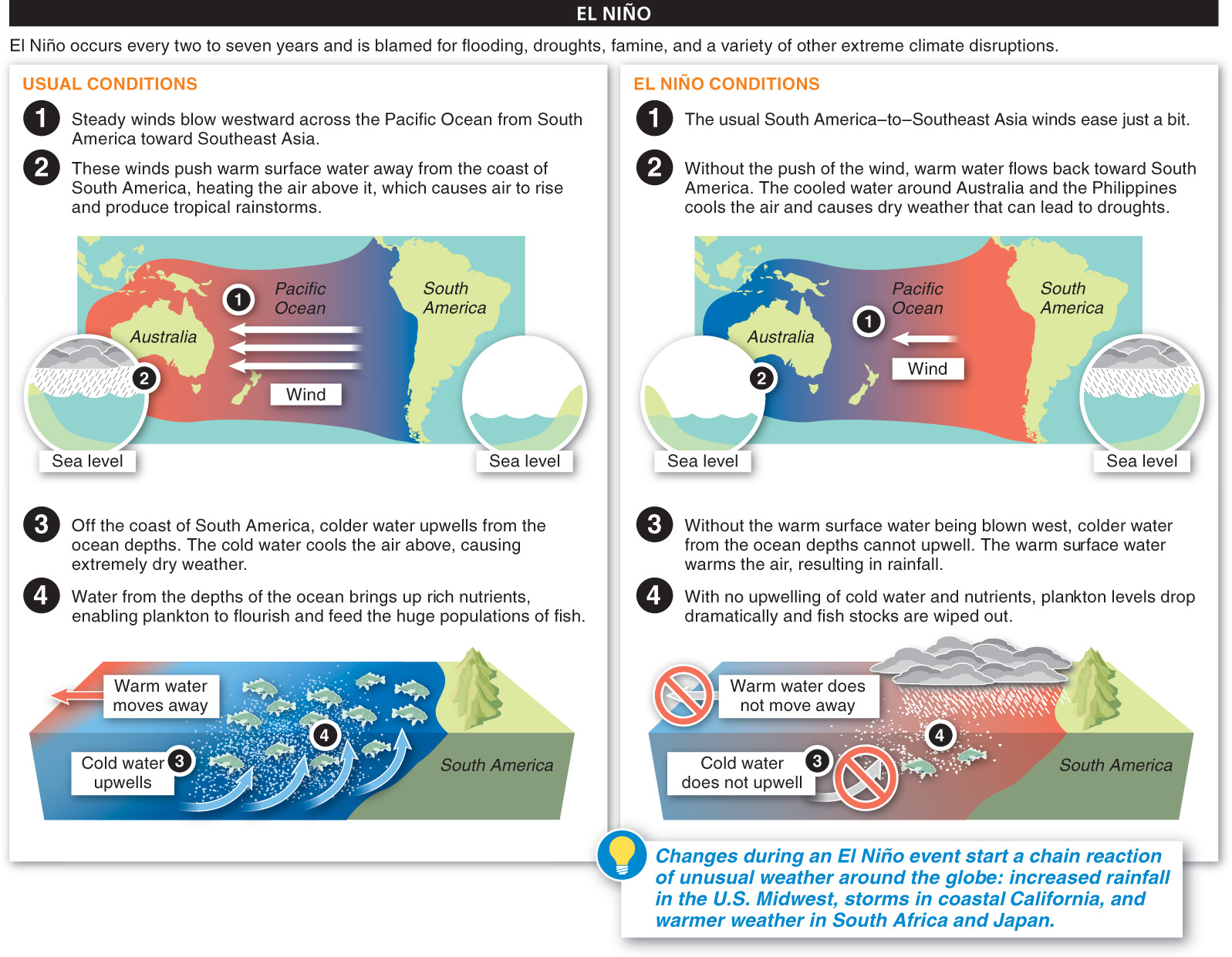

Every two to seven years, a dramatic climate change driven by ocean currents, called El Niño, causes a sustained surface temperature change in the central Pacific Ocean. It is blamed for flooding, droughts, famine, and a variety of other extreme climate disruptions. We can more easily understand El Niño if we contrast it with the more common climate pattern, as illustrated in FIGURE 15-11.

These predictable changes during an El Niño event can start a global pattern of unusual weather. Although the mechanisms aren’t clear, in El Niño years, more rain falls in the Midwestern United States and storms form off the coast of California, while South Africa, Japan, and Canada enjoy warmer weather than usual. The counterpart of the El Niño phenomenon is called La Niña. During La Niña periods, ocean surface temperatures are lower than usual, and the climate effects are approximately opposite to El Niño effects.

619

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 15.5

Oceans have global circulation patterns. Disruptions in these patterns occur every few years and can cause extreme climate disruptions around the world.

What is “El Niño”? What are some of the effects of El Niño on global weather?

El Niño is a dramatic climate change driven by ocean currents. The typical east-to-west winds that blow across the Pacific Ocean are reduced, which causes a global domino effect, including: more rainfall in coastal California and the U.S. Midwest, droughts in Australia and Southeast Asia, as well as warmer weather in Japan and South Africa.

620