You are familiar with the oxygen you breathe—

If you live in a city, you are likely to hear radio and television warnings of high ozone levels during the summer. These warnings announce that ozone is expected to exceed safe levels that day. Children and adults with lung disease are advised to remain indoors during an ozone alert.

If ozone makes people sick, why would anyone worry about depletion of ozone in the atmosphere? Isn’t that a good thing? The answer is, in the words of the old saying about what determines the value of real estate, “Location, location, location.” At ground level, ozone is bad for you, but ozone in the lower part of the stratosphere, which is 30 miles (50 km) above the earth’s surface, protects you from ultraviolet radiation, the rays that cause sunburn and skin cancer. Ozone is a Jekyll-

There are two types of “ozone depletion”: the general reduction in the amount of ozone in the stratosphere and the formation of areas with very low ozone concentration (called “ozone holes”) over the North and South Poles every winter. Synthetic chemicals known as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) are the villains in both forms of ozone depletion. CFCs, which were developed in the 1930s, have a wide range of applications, including use as coolants in refrigeration systems. When CFC molecules leak into the atmosphere, they rise to the stratosphere, where sunlight knocks a chlorine atom off the CFC molecule. These free chlorine atoms then catalyze the breakdown of ozone to oxygen (FIGURE 16-30).

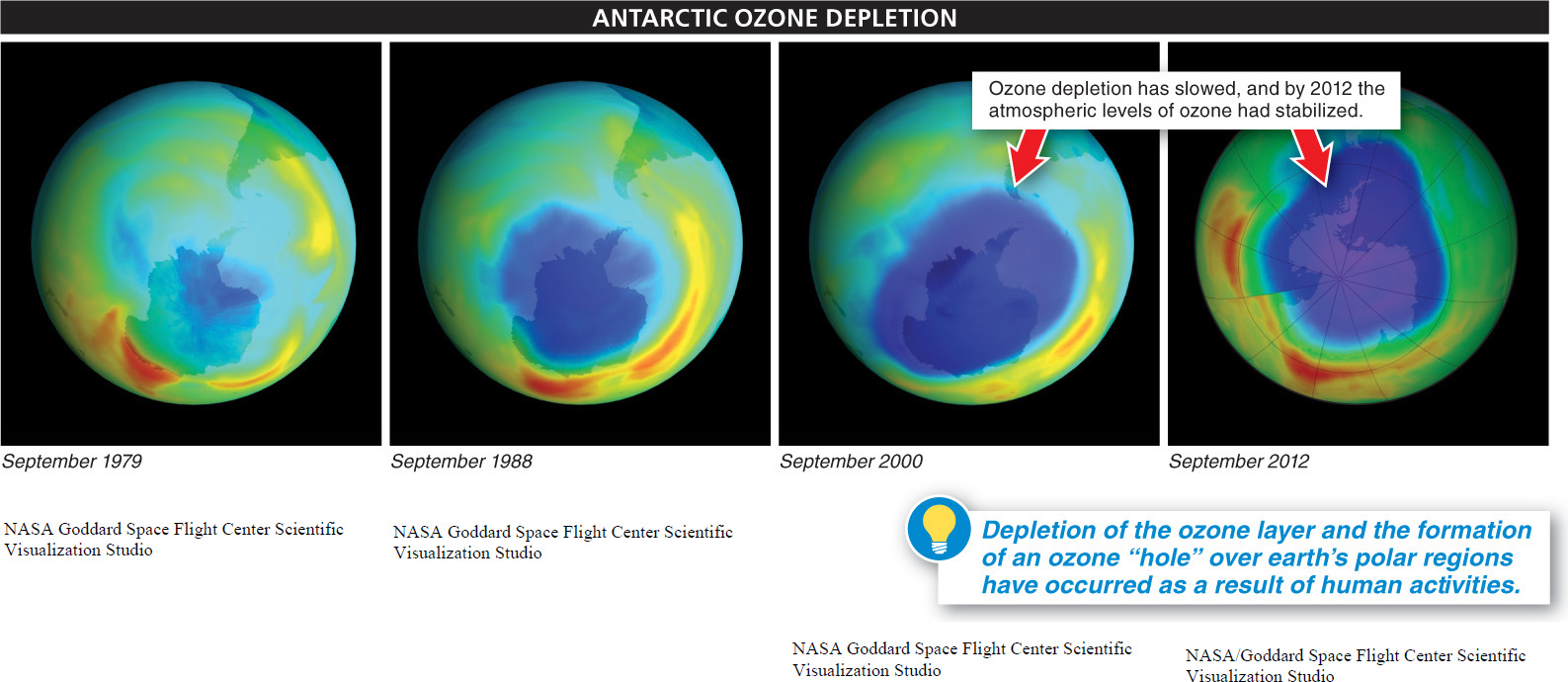

In the 1970s, scientists noted that the amount of ozone in the stratosphere was decreasing by about 4% per decade. The cold temperatures and circular flows of air that develop over the Poles during the winter concentrate CFCs, forming ozone holes in those locations. The Antarctic ozone hole, which lasts for several months, covers the entire continent of Antarctica and extends northward to include the southern tips of South America and Australia (FIGURE 16-31). The Arctic ozone hole is smaller than the Antarctic hole and does not last as long, but it is large enough to extend southward into northern Europe, Asia, and North America.

675

Should we be concerned about an ozone hole in our atmosphere?

Ozone depletion allows short-

Beyond the health risks associated with the higher UVB radiation, the damage to ecosystems is an even more serious consequence of ozone depletion. UVB radiation reduces the rate of photosynthesis by plants, and reduced photosynthesis in agricultural ecosystems means that crop yields decline.

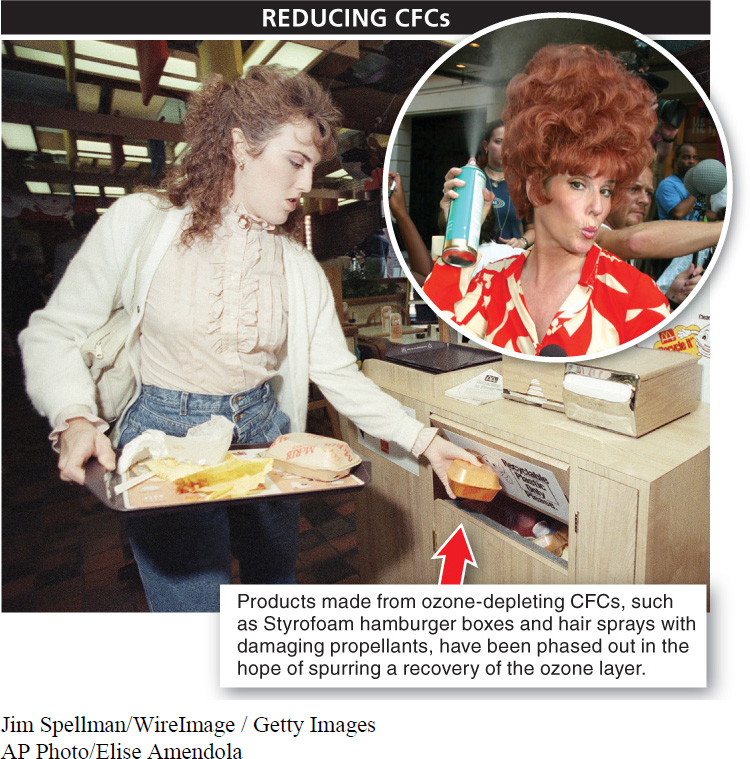

Fortunately, the worldwide response to the dangers accompanying creation of the ozone holes is an encouraging example of effective integration of science and policymaking. When CFCs were first invented, they were considered harmless, and so their use as coolants, as aerosol propellants, and in the production of materials such as Styrofoam became widespread. But the recognition that CFCs eventually reach the highest levels of the atmosphere and catalyze the destruction of the protective ozone layer prompted relatively quick reaction and efforts to find solutions (FIGURE 16-32) With the adoption by most countries, in the 1980s, of an agreement to discontinue the use of CFCs, ozone depletion was slowed. And in 2010, scientists found that the atmospheric levels of ozone had stabilized. A full recovery could occur by 2050.

676

It’s important to note that depletion of the ozone layer is not the mechanism of global warming. Ultraviolet radiation represents less than 1% of the sun’s energy. And the greenhouse gases we discussed earlier do not reduce the atmosphere’s ozone layer. Global warming and ozone depletion are largely unrelated environmental issues, linked only by their common cause: human activities. The response to ozone depletion, however, represents an encouraging example of how nations can work together to address and correct human-

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 16.12

Ozone in the stratosphere prevents short-

What is ozone? Why has the hole in the earth’s ozone layer been such a concern for decades, and what measures have been taken to reverse the trend?

Ozone is a molecular arrangement of oxygen with 3 oxygen atoms in a molecule. In earth’s stratosphere, ozone protects us from ultraviolet radiation. Ozone depletion and holes in the ozone layer allow increased levels of ultraviolet light to reach earth’s surface, leading to health problems, including skin cancer, and decreased photosynthesis in plants. Scientists determined ozone depletion was the result of manmade chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), leaking into our atmosphere. In the 1980s, most nations banned the use of CFCs. Ozone levels have since stabilized, and a full recovery could happen by 2050.