Phloem is the food-

When a leaf is young, it cannot produce adequate food for itself; instead, it receives food supplied through the phloem. Once the leaf is mature and making more food than it can use, the transport direction is switched to move sugar out of the leaf, into the phloem, and to other places in the plant where it is needed. So, unlike mammalian circulatory systems, the phloem isn’t necessarily a system of one-

Phloem vessels are visible to the naked eye. Along with the xylem vessels, they make up the veins in a leaf. The phloem vessels are living cells lined up end to end so that they form a pipeline, called a sieve tube. The cells of the sieve tubes have many small openings in their walls (primarily in the ends of the cells) and so can quickly move the sugar produced in the leaves throughout the plant to roots, stems, buds, flowers, and fruits. The process is called the pressure-

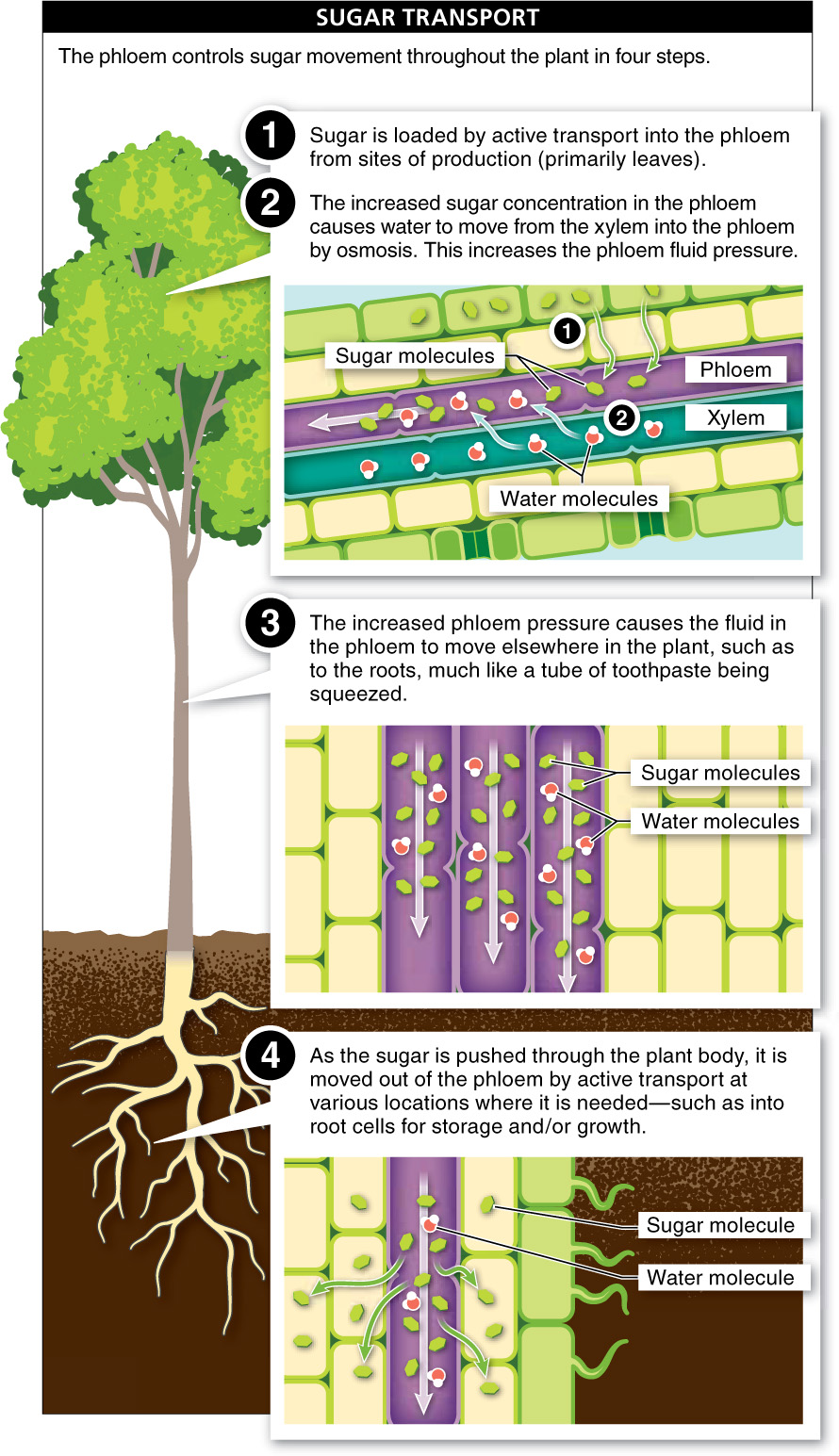

Phloem controls sugar movement throughout the plant in four steps (FIGURE 17-36).

- 1. At its source (primarily leaves), sugar is loaded into the phloem by active transport.

- 2. Water moves from the xylem into the phloem by osmosis because of the increased sugar concentration in the phloem. This increases the pressure inside the phloem.

- 3. The increased pressure (particularly higher up in the plant, where photosynthesis is occurring) causes the fluid in the phloem to move to other parts of the plant.

- 4. Sugar is moved out of the phloem at various locations where it is needed (the sinks) by active transport.

717

Sometimes, important science questions can be answered by unexpected methods. Consider this question: what exactly is the fluid circulating in the phloem? To answer this, researchers used aphids—

The researchers found plants on which aphids were feeding, then removed the bodies off the aphids, leaving their mouthparts sticking into the phloem like tiny syringes. As the sap dripped out, the researchers collected and analyzed it. As it turns out, phloem sap is a sugar solution, of which about 10% to 25% is dissolved solids that include some lipids and amino acids. In most plants, about 90% of the phloem sugar is sucrose, the same molecule we use as table sugar.

Aphids helped answer an important question about plants, but they can also be a nuisance. If you have ever wondered why your car gets covered in a sticky substance under some trees, you can blame aphids. When aphids are attacking a tree, puncturing holes in the plant tissues to feed on the phloem sap, the pressure in the phloem fluid can cause more of the fluid to come out than the aphids can use. The excess sugary (and sticky) fluid secreted by the aphids, called honeydew, drops onto the ground (or your car) below.

In the next chapter, we see that as a tree grows, phloem also takes on a secondary, protective function.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 17.14

The phloem consists of a branching network of vessels made from living cells lined up end to end to form sieve tubes, with small openings in their end walls and side walls. Sugar, usually sucrose, is moved in the phloem from sites of production (sources) to sites of use or storage (sinks). The direction of flow is not always the same: a plant part may be a source at one time and a sink at another.

Is a plant's leaf a sugar “source” or a sugar “sink”?

Yes to both, but at different times. A young leaf is a sugar “sink,” as its growth requires more sugar than it produces. Once mature, the leaf is a sugar “source,” and these excess sugars are transported out for use elsewhere.

718