The ancestors of plants, the green algae, could simply release their gametes into the water, and some were bound to find their way to the gametes of another individual of their species. For mosses and ferns, reproduction is still tied to water; they must rely on the presence of water for transporting male gametes to the female gametes, or the gametes will dry out. For this reason, mosses and ferns must live in moist habitats or reproduce when moisture is available. With the transition to drier habitats, seed plants had to reduce their dependence on water for gamete transport, and a number of ways evolved that bring together male and female gametes (FIGURE 18-16). No matter the method, though, a pollen grain from a plant must journey to the stigma of another plant of the same species. This process is called pollination.

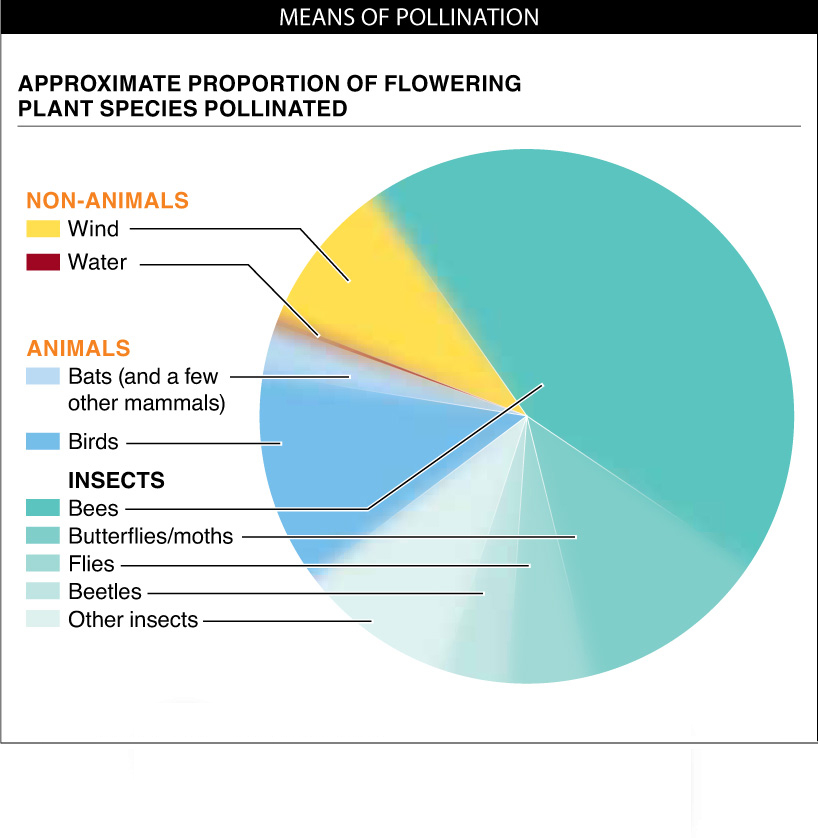

About 10% of plant species achieve pollination by simply releasing their pollen into the wind (as do grasses and pine trees) or into water (as does eelgrass, for example), on the slim chance that—

739

In the other 90% of plants, animals act as “go-

A flowering plant attracts the animal with its flowers’ visual cues (color, shape), olfactory cues (smell), or even tactile cues (soft, bristly, hard, rough, smooth). Regardless of the method of attraction, the goal is always the same: to attach some male gametes to an animal’s body so that they will rub off on the female reproductive parts of another plant, where fertilization can then occur.

Most animal-

How does a flowering plant get an animal to transport its gametes? Plants make use of two different and clever strategies for achieving pollination (FIGURE 18-18): (1) bribery—

740

Why do some flowers smell nice while others don’t smell at all?

1. Bribery. The most common strategy for achieving pollination is for a plant to offer something of value to an animal in exchange for transport of its pollen from one flower to another. For bribery to work, the plant must produce sticky pollen and a flower that catches the attention of the pollinator. Most important, the plant must produce something of value to the pollinator. The payoff can be food-

2. Trickery. The second strategy for achieving pollination is more selfish. Rather than bribing an animal to carry its pollen, the plant just tricks the animal into perceiving that it is going to get something of value, while not actually giving it anything. Among the tricksters is a species of plants called cycads. Cycads are gymnosperms (they look a bit like palm trees) that produce cones once every year or so. Within the male cones, pollen is produced in large amounts. It might seem as though cycads use the strategy of bribery for pollination, because their pollen attracts huge numbers of small insects called thrips, and the thrips consume the pollen. But trickery is also necessary to achieve pollination in cycads.

For a few hours each day during the period when they have cones, the cycads are able to increase the temperature inside the male cones by up to 25° F. They do this by metabolizing sugars and fats within the cone. As they do so, they also produce a powerful stench. Taken together, the heat and stink cause the thrips—

The variety of flower structures is tremendous. Flowers differ in shape, color, smell, time of day when open, whether or not they produce nectar, and whether their pollen is edible. The variety of pollinator types is also impressive, as we’ve seen: birds (mostly hummingbirds), bees, flies, beetles, butterflies, moths, some mammals (mostly bats), and even lizards. In each case, there has been strong coevolution between the plants and their pollinators: the plants have become more and more effective at attracting the pollinators and deterring other species from visiting the flower, while the pollinators have become more and more effective at exploiting the resources offered by the plants (see Figure 12-21).

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 18.7

Plants usually employ trickery or bribery to get the assistance of animals in carrying the male gametes to the female gametes. There has been strong coevolution between plants and their animal pollinators.

Give two examples of a payoff an animal pollinator may receive from a flower.

The animal pollinator may receive nutrient-rich nectar or a safe place to lay its eggs. You may be able to think of other examples.