It’s a brand new age, and science, particularly biology, is everywhere. To illustrate the value of scientific thinking in understanding the world, let’s look at what happens in its absence, by considering some unusual behaviors in the common laboratory rat.

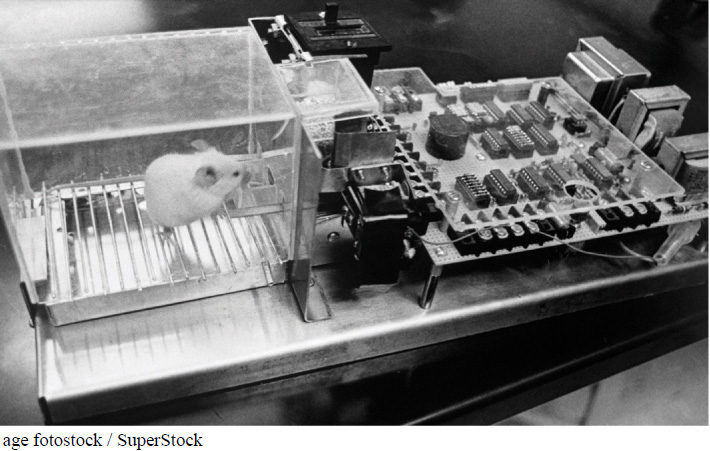

Rats can be trained, without much difficulty, to push a lever to receive a food pellet from a feeding mechanism (FIGURE 1-3). When the mechanism is altered so that there is a 10-

In another cage, with the same 10-

Why do people develop superstitions? Can animals be superstitious?

In cage after cage of rats with these 10-

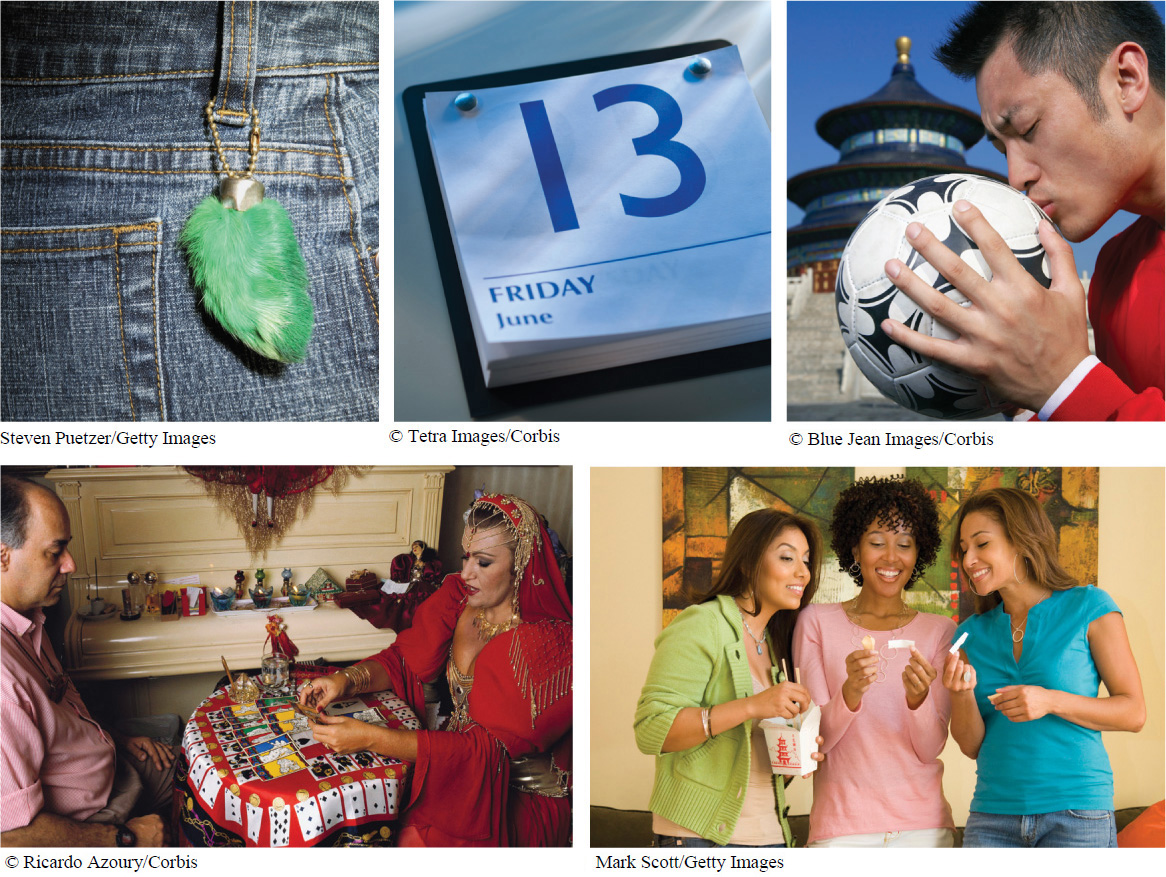

Humans can also mistakenly associate actions with outcomes in an attempt to understand and control their world. The irrational belief that actions or circumstances that are not logically related to a course of events can influence its outcome is called superstition (FIGURE 1-4). For example, Nomar Garciaparra, a former major league baseball player, always engaged in a precise series of toe taps and adjustments to his batting gloves before he would bat.

Thousands of different narratives, legends, fairy tales, and epics from all around the globe exist to help people understand the world around them. These stories explain everything from birth and death to disease and healing.

6

As helpful and comforting as stories and superstitions may be (or seem to be), they are no substitute for understanding achieved through the process of examination and discovery called the scientific method.

The scientific method usually begins with someone observing a phenomenon and proposing an explanation for it. Next, the proposed explanation is tested through a series of experiments. If the experiments reveal that the explanation is accurate, and if others complete the experiments with the same result, then the explanation is considered to be valid. If the experiments do not support the proposed explanation, then the explanation must be revised or alternative explanations must be proposed and tested. This process continues as better, more accurate explanations are found.

While the scientific method reveals much about the world around us, it doesn’t explain everything. There are many other methods through which we can gain an understanding of the world. For example, much of our knowledge about plants and animals does not come from the use of the scientific method, but rather comes from systematic, orderly observation, without the testing of any explicit hypotheses. Other disciplines also involve understandings of the world based on non-

Scientific thinking can be distinguished from these alternative ways of acquiring knowledge about the world in that it is empirical. Empirical knowledge is based on experience and observations that are rational, testable, and repeatable. The empirical nature of the scientific approach makes it self-

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 1.3

There are numerous ways of gaining an understanding of the world. Because it is empirical, rational, testable, repeatable, and self-

How does science differ from other ways of acquiring knowledge about the world?

Science is empirical. Empirical knowledge is based on experimentation and observation. Empirical results can be tested again and again and corrected as needed. Scientists use the scientific method to produce empirical results.

7