Once we have formulated a hypothesis that generates a testable prediction, we conduct a critical experiment, an experiment that makes it possible to decisively determine whether a particular hypothesis is correct. There are many crucial elements in designing a critical experiment, and Section 1-

In this step of the scientific method, a bit of cleverness can come in handy. Suppose we were to devise a critical experiment to test our hypothesis “Eyewitness testimony is always accurate.” First, we stage a mock crime such as a purse snatching in front of a group of observers who do not know the crime is staged. Next, we ask observers to identify the criminal. To one group of observers we might present six “suspects” all at once in a lineup. To another group of observers we might present the six suspects one at a time. The beauty of this experiment is that we actually know who the “criminal” is. With this knowledge, we can evaluate with certainty whether an eyewitness’s identification is correct or not.

This exact experiment was done, but with an additional, devious little twist: the researcher did not include the actual “criminal” in any of the lineups or one-

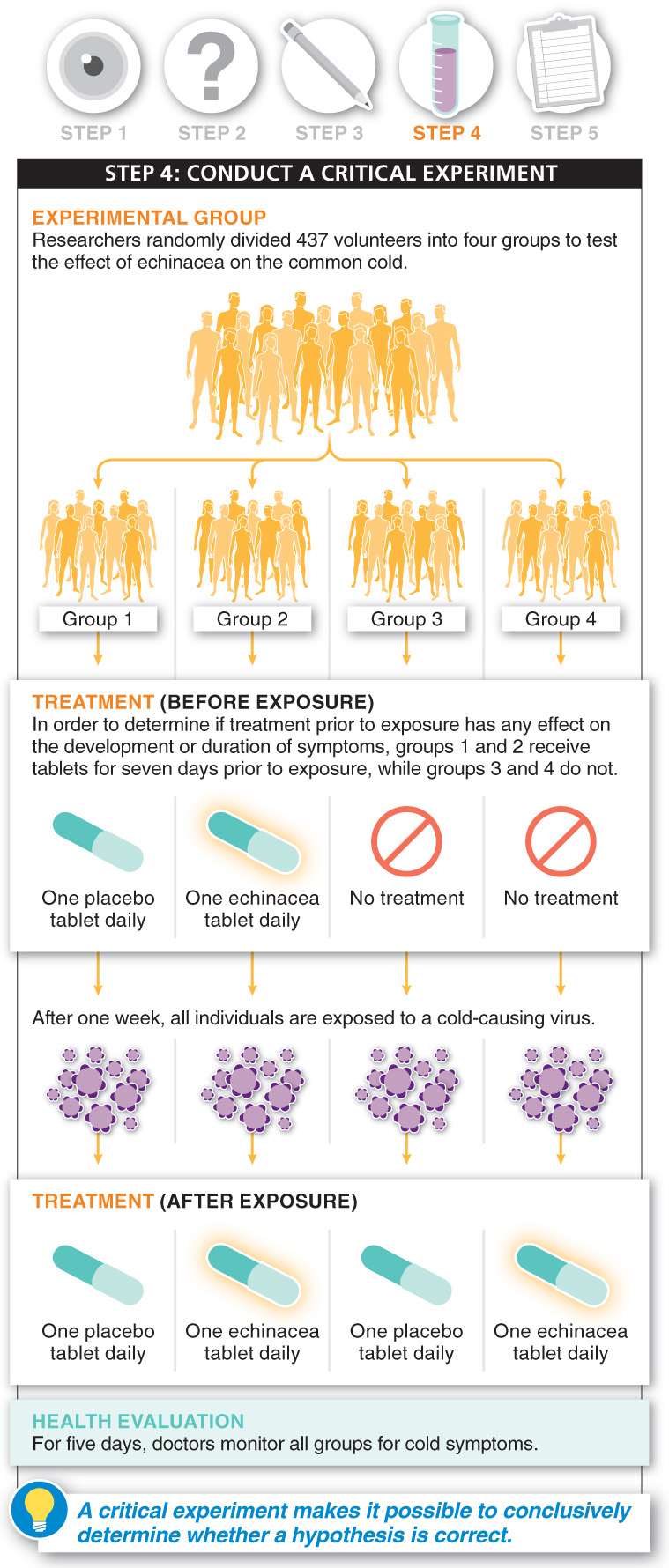

Hypothesis: Echinacea reduces the duration and severity of the symptoms of the common cold. The critical experiment for the echinacea hypothesis has been performed, and it is about as close to a perfect experiment as possible. Researchers began with 437 people who volunteered to be exposed to viruses that cause the common cold. Exposure to the cold-

12

Before the cold virus treatment, the volunteers were randomly divided into four groups. In two of the groups, each individual began taking a pill each day for a week prior to exposure to the virus. Those in one group received echinacea tablets, while those in the other took a placebo, a pill that looked identical to the echinacea tablet but contained no echinacea or other active ingredient. Neither the subject nor the doctor administering the tablets (and later checking for cold symptoms) knew what they contained. In the other two groups, the individuals did not begin taking the tablets until the day they were exposed to the cold virus. Again, one group got the echinacea and the other group got the placebo.

13

Does shaving or cutting hair make it grow back more thickly?

Hypothesis: Hair that is shaved grows back coarser and darker. A critical experiment does not have to be complex or high-

In the next section we’ll see how our hypotheses survive being confronted with the results of these critical experiments and how we can move toward drawing conclusions.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 1.8

A critical experiment is one that makes it possible to decisively determine whether a particular hypothesis is correct.

Design a critical experiment that determines whether the hypothesis you listed in the previous question is correct.

The textbook describes experiments designed to determine the validity of hypotheses concerning eyewitness testimony, echinacea, and the coarseness of shaved hair. Like the sample experiments in the textbook, make sure your experiment has two or more groups of subjects that receive different treatments, which will allow you to compare the results.