Organisms, whether they live in the water or on land, require water. But they can’t take in too much or they will burst. And they can’t lose too much or they will shrivel up and die. Osmoregulation, an important component of homeostasis in animals, is the regulation of water content and of the concentrations of dissolved solutes that influence osmosis. The most abundant solutes in animal fluids are sodium, chloride, potassium, magnesium, and calcium ions.

Although a variety of mechanisms of water regulation have evolved in animals, there are just four ways that animals get water: by drinking it, by eating foods that contain it, by absorbing it through osmosis, and as a by-

Osmoregulation revolves around controlling and regulating these mechanisms of water loss and gain. Through osmosis (see Section 3-

Because animals live in such a wide range of habitats, they encounter a similarly wide range of osmoregulatory challenges. The challenges are very different for aquatic organisms than for terrestrial organisms, for example. And among the aquatic organisms, the challenges faced by organisms living in saltwater habitats are very different from—

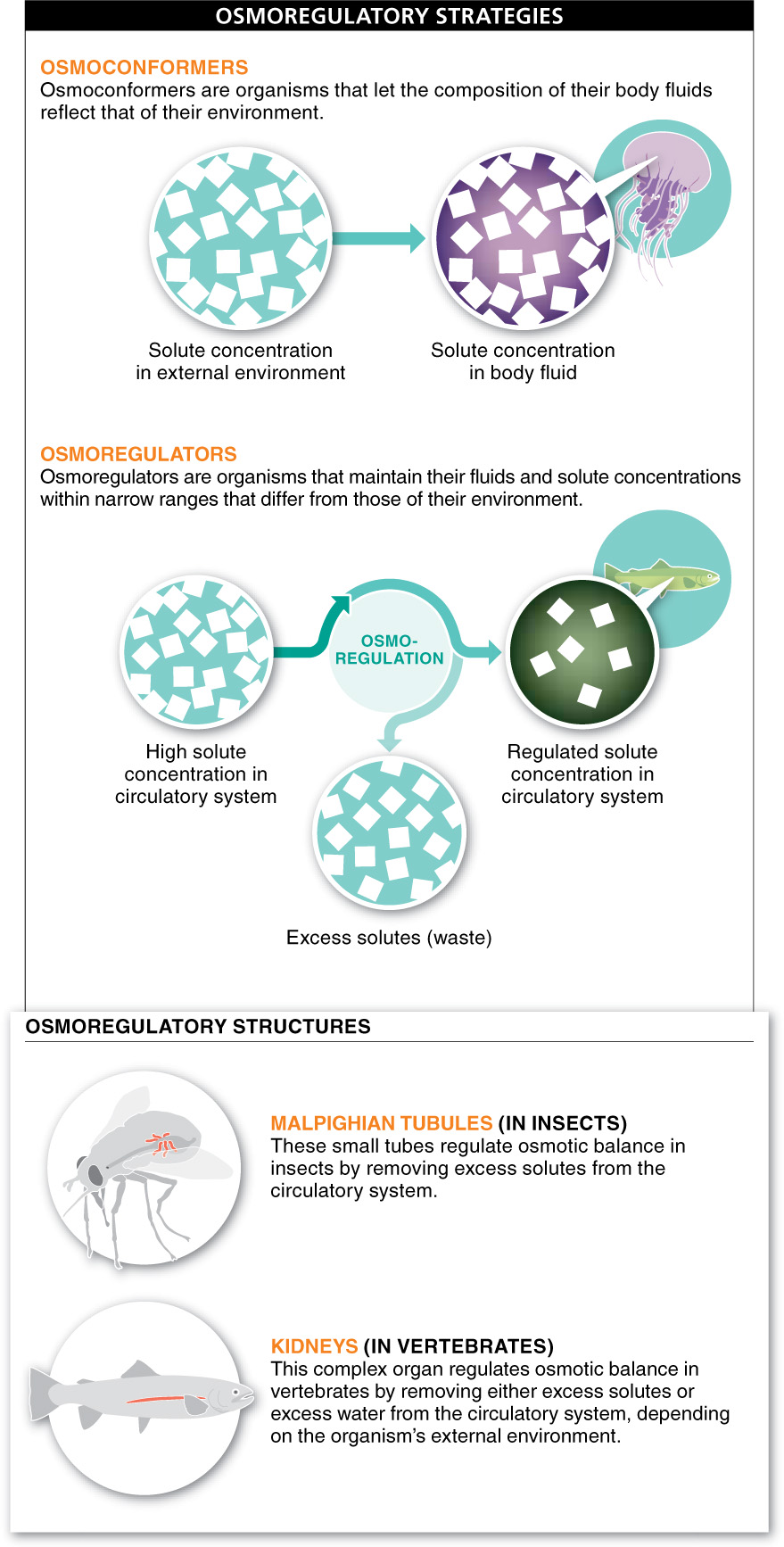

Most invertebrates that live in salt water are osmoconformers, meaning that they let the solute concentration of their body fluids reflect that of their environment. Most vertebrates, on the other hand, are osmoregulators, maintaining their fluids and solute concentrations within narrow ranges that differ from those of their environment (FIGURE 20-23; see also Figure 20-16).

A variety of structures have evolved that enable animals to regulate their water balance. In insects, for example, very small tubes branch off the digestive tract, near its end at the rectum. These extensions from the gut, called Malpighian tubules, function as insects’ chief excretory organs. Potassium ions (K+) and cellular waste products move by active transport from the body cavity of the insect—

816

Do fish drink water?

Another osmoregulatory structure is the vertebrate kidney. The kidney, as we shall see, is a complex organ that filters blood, removing metabolic waste products—

In the next section, we examine the details of kidney functioning, focusing specifically on the human kidney and how it can produce urine that has a solute concentration more than four times that of blood, and how it can eliminate the many potentially harmful molecules contained in the food and drink that we consume.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 20.12

Many organisms maintain their water content within a narrow range. To maintain osmotic balance, organisms must be able to take up water and get rid of water, and they must be able to regulate concentrations of ions in their body fluids. Various mechanisms and strategies have evolved for coping with these challenges.

Organisms gain water by drinking it, by eating foods that contain it, by absorbing it through osmosis, and as a by-

Organisms lose water through urination, defecation, evaporation, and osmosis.

817