Feel your pulse. With no fancy equipment at all, it is possible to get very useful information about the functioning of your heart. For some arteries, such as those on the underside of your wrist or the side of your neck, you can feel with your fingers the pressure increase as a blood surge stretches the arteries with each contraction of the heart. Taking a person’s pulse provides a quick and easy determination of the rate and rhythm of the heartbeats.

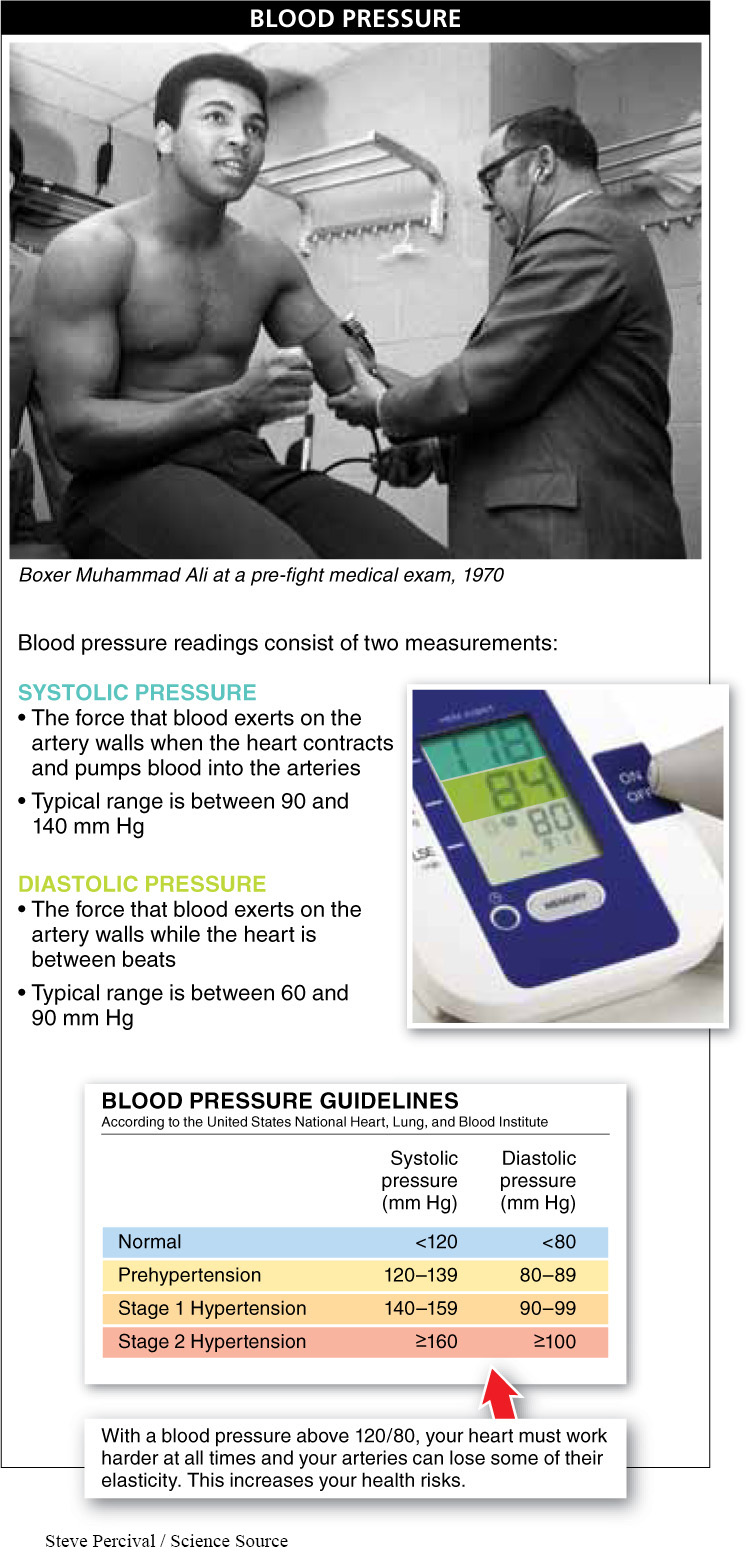

Additional information about heart health can be gained by measuring blood pressure, the force with which blood flows through a person’s arteries. This force tells us the magnitude of each heart contraction and gives important clues about an individual’s cardiovascular health. There are two different parts to a blood pressure reading (FIGURE 21-18). The first, called systolic pressure, is the pressure when the heart contracts. The powerful contraction pumps blood into the arteries, momentarily causing them to stretch as they accommodate the large pulse of blood. The second blood pressure reading is called diastolic pressure. This is a measure of the force that blood exerts on the artery walls while the heart is between beats. Because blood isn’t being actively pumped at that moment, the diastolic pressure is always lower than the systolic pressure.

Blood pressure can be measured in four easy steps, using a blood pressure cuff.

- 1. The cuff is fastened around the upper arm and pumped up, clamping off the arteries in the arm so that no blood gets through.

- 2. Gradually, pressure on the cuff is released.

- 3. When the pulsing of blood getting pushed through the arteries under the cuff can first be heard—

as a little squirt— with a stethoscope held to the arteries just below the cuff, the pressure reading is noted. This is the systolic pressure. Each contraction of the heart is just strong enough to push blood through the barrier of that much pressure. - 4. Additional pressure in the cuff is released until the squirting sound disappears. The pressure at that point is the diastolic pressure. Blood is flowing through the arteries with this amount of pressure between heart contractions.

If your blood pressure is “120 over 80,” it means that the systolic pressure is 120 and the diastolic pressure is 80. This is written as 120/80, and the units of measure are millimeters of mercury (mm Hg), representing how high a column of mercury could be lifted by such pressure.

846

Blood pressure above 120/80 is a potential health hazard. In its guidelines concerning high blood pressure (also called hypertension), the U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute released the following definitions:

Normal blood pressure: systolic = less than 120, and diastolic = less than 80 mm Hg

Prehypertension: systolic = 120–

Stage 1 hypertension: systolic = 140–

Stage 2 hypertension: systolic = 160 or greater, or diastolic = 100 or greater mm Hg

Why is high blood pressure cause for concern? Imagine a pair of shorts with an elastic waistband. If you were to stretch the waistband as far as possible and hold it in that position for a long time, what would happen? The waistband would lose its elasticity. This is similar to what happens to your arteries if they are stretched by high pressures for long periods of time. With high blood pressure, not only must your heart work harder at all times, potentially weakening it, but your arteries have a reduced ability to expand and accommodate the increasing pulses of blood during times of exertion. Moreover, more cholesterol sticks to artery walls when they are rigid than when they are elastic, and as the cholesterol buildup narrows the diameter of the blood vessel, it further reduces the efficiency of the circulatory system and taxes the heart. These problems all increase the risk of catastrophic heart attacks and strokes, which we discuss in Section 21-

At the other extreme, low blood pressure, or hypotension, is defined as a pressure of 90/60 or lower. It can cause symptoms such as dizziness, particularly just after a person stands up, due to inadequate blood flow to the brain. Sometimes caused by medications, low blood pressure can also be associated with weakness or depression. Most often it is not a problem, and it rarely carries long-

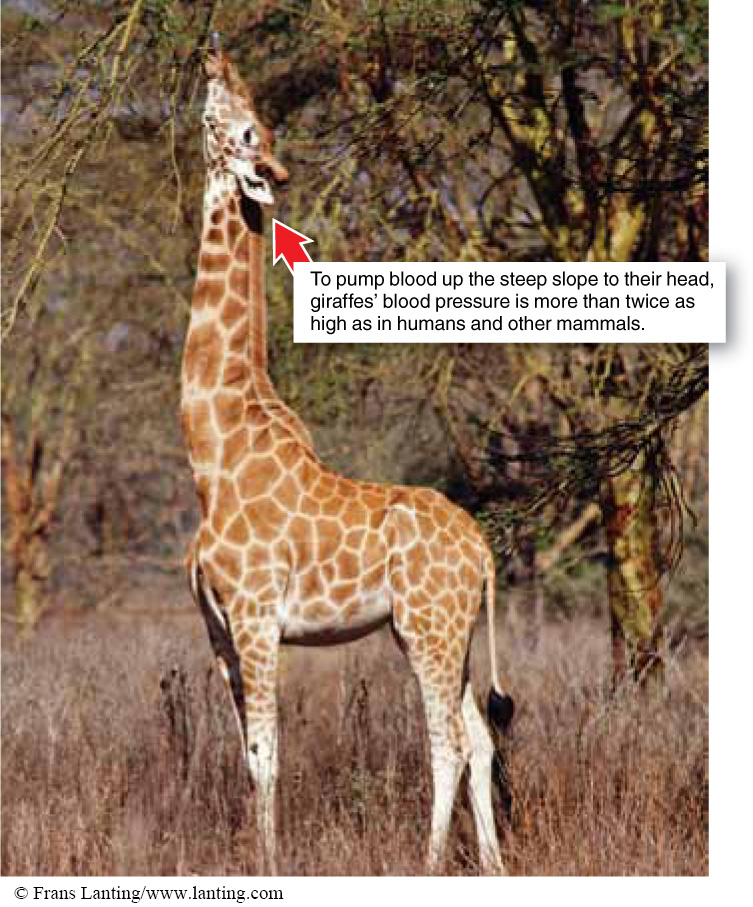

Blood pressure is consistent among all mammals, with one notable exception: giraffes. With their necks stretching 8 feet (2.5 m) or more above the heart (and extremely long legs), giraffes must pump blood up a pretty steep slope and retrieve it from far below (FIGURE 21-19). Although the size of their heart relative to their body size is similar to that of most mammals, giraffes have an average blood pressure that is more than twice as high as that in humans and other mammals (and at times their blood pressure is more than five times that in humans). Scientists have begun studying giraffe circulation in the hope of learning physiological secrets to help humans cope with high blood pressure. Why, for example, with such high blood pressure, doesn’t a giraffe’s head explode when it is lowered to drink from a pond? (At least part of the answer may be that giraffe blood vessels are extremely thick.)

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 21.9

Blood pressure measurement gives important clues about an individual’s cardiovascular health. A blood pressure reading consists of two measures. The first, systolic pressure, is the force that blood exerts on the artery wall when the heart contracts and pumps blood into the arteries. The second, diastolic pressure, is the force that blood exerts on the artery wall while the heart is between beats. With high blood pressure, the heart must work harder at all times, the arteries can lose some of their elasticity, and health risks are increased.

In a person with high blood pressure, the heart must work harder at all times and can potentially be weakened. What are some of the other effects of high blood pressure?

Arteries have a limited capacity for expansion and cannot easily accommodate the increasing pulses of blood during times of exertion. Also, more cholesterol sticks to artery walls when they are rigid than when they are elastic. In turn, this can narrow the diameter of the blood vessel and further reduce circulatory system efficiency and tax the heart.

847