Breathe in. Breathe out. It all seems simple enough. You don’t even have to think about it. But over the course of your life, this simple process will happen 500 million times without fail. How does it work?

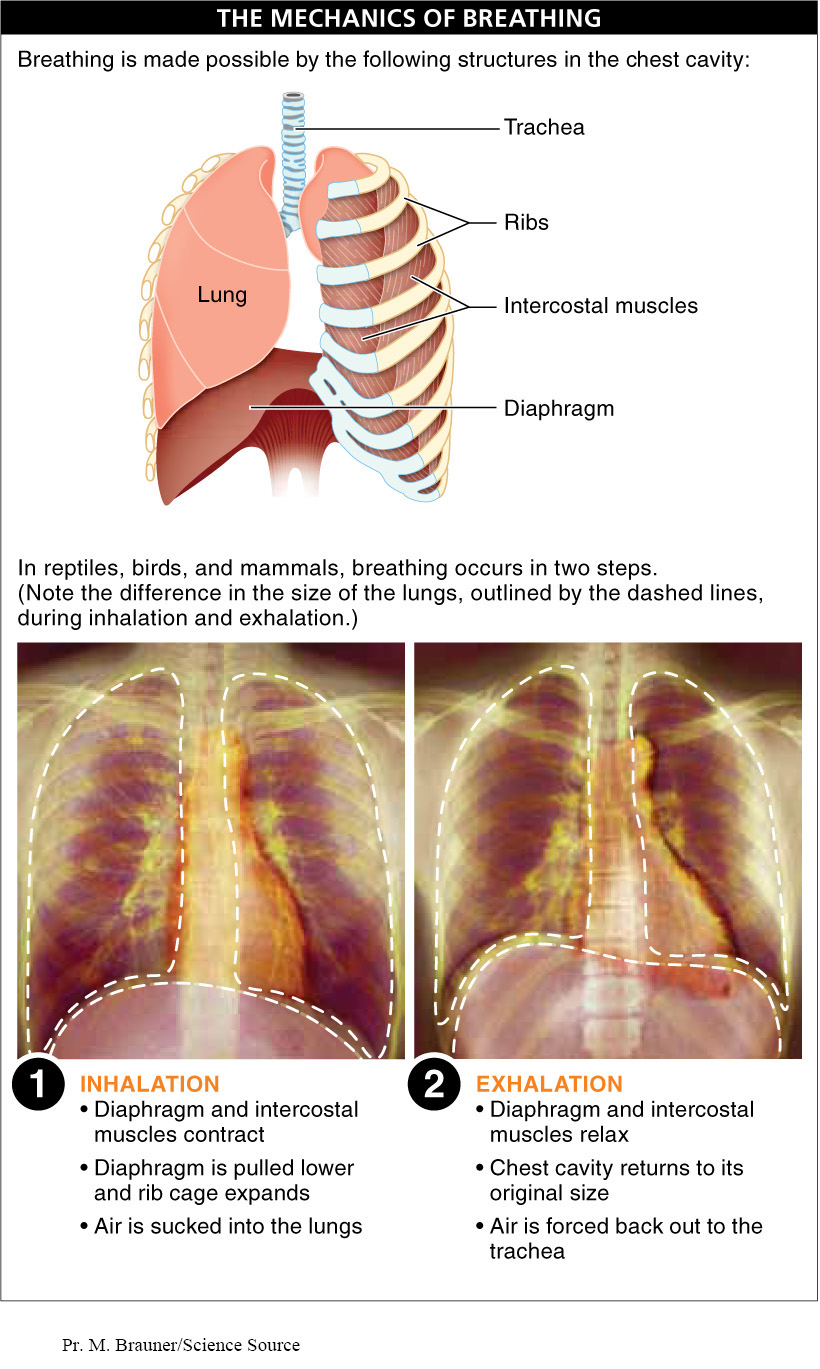

In reptiles, birds, and mammals, breathing occurs in two steps: inhalation and exhalation (FIGURE 21-37). The chest cavity is bordered on the bottom by a large sheet of muscle called the diaphragm, which separates the chest cavity from the abdominal cavity. The rest of the chest cavity is surrounded by the rib cage and the intercostal muscles between the ribs. During inhalation, the diaphragm and external intercostal muscles contract; the diaphragm is pulled down and the intercostal muscles lift the ribs and expand the rib cage. This causes a rapid increase in the volume of the chest cavity and lungs, which causes air to be sucked into the lungs. When the diaphragm and intercostal muscles relax, the chest cavity returns to its original size. This reduction in volume compresses the lungs and forces air back out.

“I’m going to hold my breath until I die.” As a child, you may have threatened your parents this way. It’s actually not possible to do this, however. Although we can consciously control our breathing to some extent, chemical sensors in the body detect when carbon dioxide levels rise dangerously high, and our brain responds by sending signals to the muscles that control our breathing, spurring them to override our efforts to stop breathing.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 21.17

In reptiles, birds, and mammals, breathing occurs in two steps: inhalation and exhalation. During inhalation, muscles contract, pulling the diaphragm down, expanding the rib cage, and increasing the volume of the chest cavity and lungs, which causes air to be sucked into the lungs. When the muscles relax, the chest cavity returns to its original size and air is forced out of the lungs.

What is the diaphragm, and what is its function in the body?

The diaphragm is a large sheet of muscle bordering the bottom of the chest cavity. This muscle's contraction causes inhalation.

863