Breathing is more difficult in some places than others. Because the diffusion of gases between the outside and inside of an animal depends on several physical factors, animals differ widely in their respiratory efficiency. One of the most important constraints on the rate at which oxygen diffuses into the blood is air pressure.

As we noted when discussing birds’ respiratory systems, at high altitudes much less oxygen is available. You don’t even need to go climbing in the Himalayas to experience this. A relatively short walk up a much smaller mountain will convince you. At 15,000 feet above sea level, for example, the air pressure is half of what it is at sea level. This is because there is less atmosphere above the air, pushing down on it (see Figure 21-28). With lower pressure from above, less oxygen is squeezed into a given volume. The lower air pressure makes it hard to push air into lungs and to drive the oxygen across the alveolar and capillary membranes and into the blood. We struggle at high elevations, because our hemoglobin isn’t designed to pick up oxygen at such a low pressure; the hemoglobin isn’t sticky enough.

Mountain climbers often carry canisters of pressurized oxygen with them. In the lungs, the high-

864

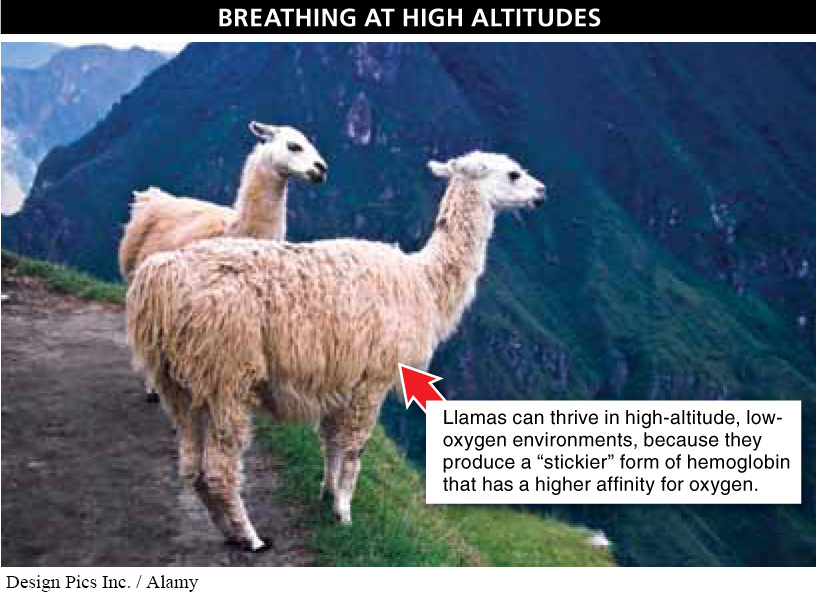

Living at elevations of about 3.1 miles (5,000 m) above sea level, llamas solve this problem by producing a slightly different form of hemoglobin. Under the low-

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 21.18

At high elevations, the amount of oxygen present is lower: breathing and activity are difficult. Animals living at high elevations solve this problem by producing a form of hemoglobin that has a higher affinity for oxygen.

What adaptation allows llamas to survive and thrive at very high altitudes where oxygen concentrations are very low?

Llamas produce a form of hemoglobin different from adult humans. This llama form of hemoglobin has a greater affinity for oxygen—much in the same way that human fetal hemoglobin has a greater affinity for oxygen than the form present in adult humans.