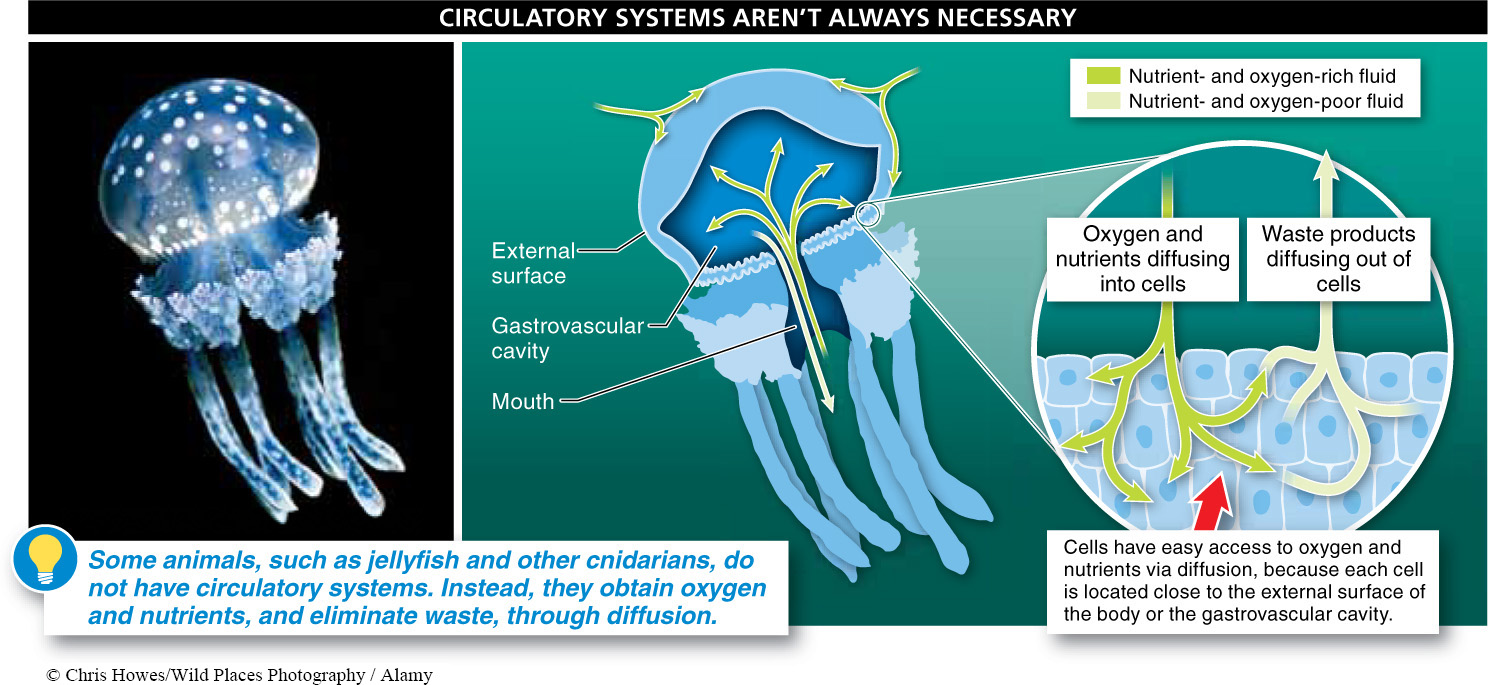

There’s more than one way to build a circulatory system. And, in fact, not all multicellular organisms even need a circulatory system. For example, in spite of their relatively large size and multicellularity, flatworms, as well as cnidarians such as jellyfish, have a body plan that gives every cell easy access to oxygen and nutrients through simple diffusion (FIGURE 21-2). This access is possible because every cell is close to the external surface of the cnidarian’s body or to its internal gastrovascular cavity. Although the gastrovascular cavity is not a true circulatory system, it serves many digestive (“gastro”) and circulatory (“vascular”) functions by directing water into the central mouth and through an elaborate system of channels. Cells lining the mouth and the channels can absorb nutrients and exchange gases by diffusion. The nutrients then diffuse to other cells, none of which are very far away. Once nutrients have been extracted (and waste products picked up), fluid in the gastrovascular cavity is flushed back out of the mouth, and the process is repeated.

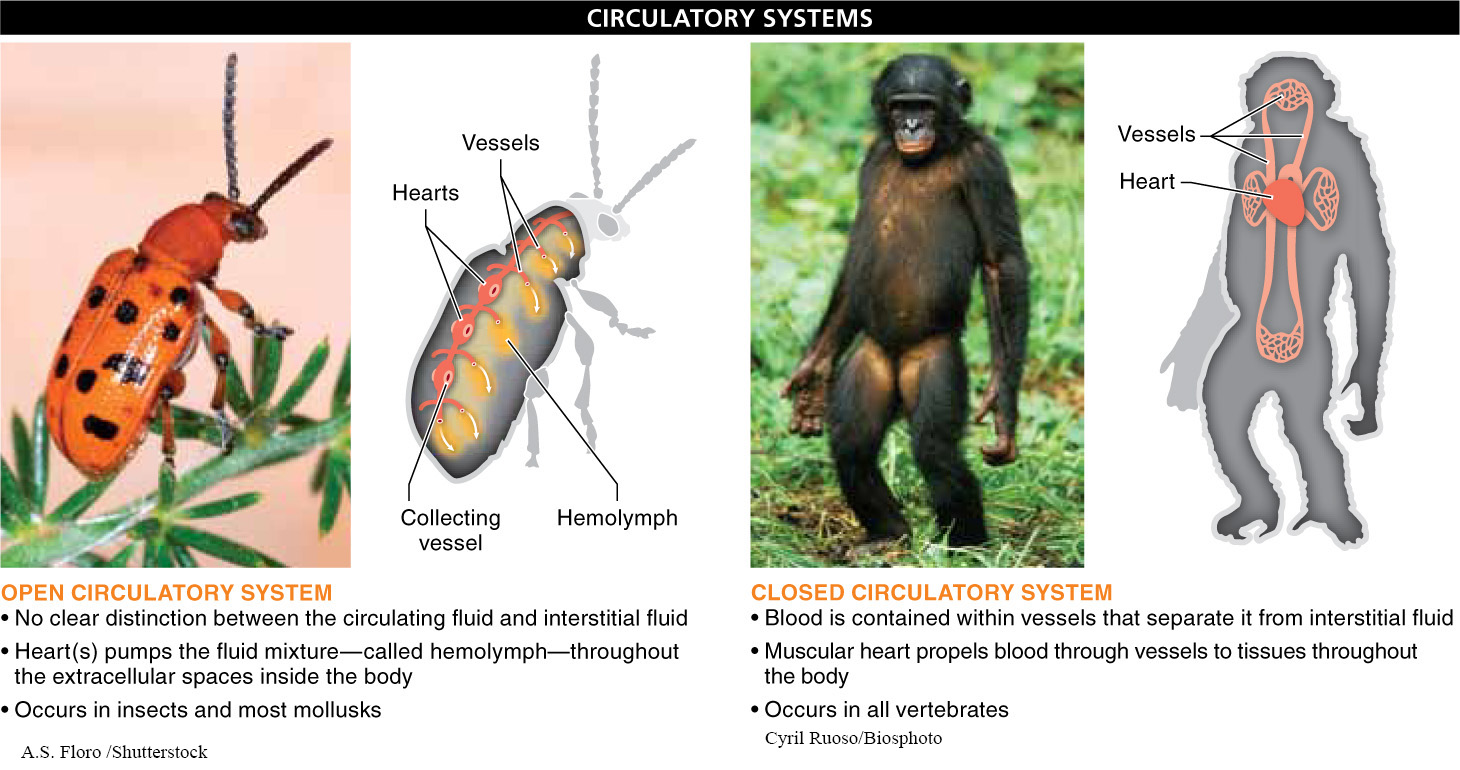

Among other multicellular animals, there are two distinct types of circulatory systems: open and closed (FIGURE 21-3). Open circulatory systems are found in insects and most mollusks, and closed circulatory systems are found in all vertebrates. The defining feature of an open circulatory system is that it has one fluid, called hemolymph, which not only circulates to transport nutrients, gases, and waste products but also surrounds each cell in the body; there is no clear distinction between the circulating fluid and the interstitial fluid, the fluid outside the cells that bathes all the body tissues. There is a heart (or sometimes many hearts!) that pumps the hemolymph, but it essentially squirts the fluid throughout the extracellular spaces. Large collecting vessels then channel the hemolymph back to the heart, where it can be pumped throughout the body again. These collecting vessels have little valves that close when the heart pumps, preventing the hemolymph from being pumped back through the same vessel from which it was collected. This one-

830

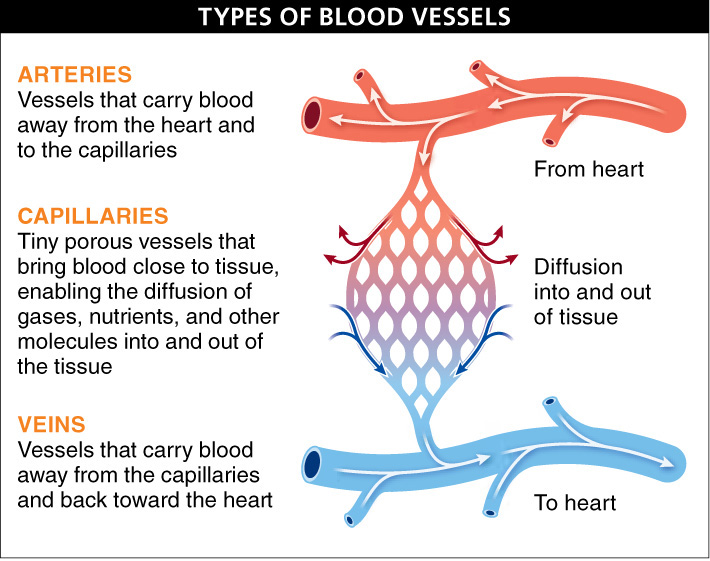

In closed circulatory systems, the circulating fluid—

831

At the organs and tissues, arteries branch into thousands upon thousands of ever-

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 21.2

Animals (such as flatworms and cnidarians) that can acquire all the nutrients and oxygen they need by diffusion do not have circulatory systems. Among animals that do have circulatory systems, the system can be open, with no clear distinction between the circulating fluid and the interstitial fluid that bathes tissues, or closed, with a clear distinction. In closed circulatory systems, the circulating fluid and interstitial fluid surrounding cells and tissues are kept completely separate.

Briefly contrast the circulatory system of a jellyfish with the circulatory system of a chimpanzee.

A jellyfish has a body plan that gives every cell easy access to oxygen and nutrients through simple diffusion. Every cell is close to the external surface or to the gastrovascular cavity, allowing diffusion of gases and nutrients to meet cellular needs; therefore, a jellyfish (or any other cnidarian) has not evolved a circulatory system. In contrast, a chimpanzee has a closed circulatory system, where the circulating fluid (blood) is always contained in a vessel as it is pumped throughout the body and is physically and chemically separated from the interstitial fluid that bathes each cell. The heart pumps the blood through blood vessels, delivering nutrients and gases to cells while also removing wastes.