Have you ever tasted salsa so spicy that it brought tears to your eyes? After you gulped down a beverage to extinguish the fire in your mouth, did you ignore the distress signals from your taste buds and head right back for more? Why would anyone seek out such culinary torture? The answer may be surprisingly simple, although not immediately apparent. We’ll start by asking the question: what are spicy foods?

Spices come from plants. Plants are rooted in the ground, and their immobility makes them easy targets for their natural enemies. But although they can’t run away, they don’t just give in to those organisms that want to eat them. They fight back chemically. Plants have evolved to produce a large number of toxic compounds to help in this fight. The presence of these noxious chemicals makes the plant toxic to would-

Humans, somewhat unexpectedly, actually seek out these toxins. We don’t think of them as toxins, though. We call them spices, and as long as they’re not too toxic, they make our food taste better. There also may be a deeper, more evolutionarily relevant reason we find our food to be more appealing with spices added. In some cases, they seem to help us in our own battles with natural enemies. “Food poisoning”—which affects about 1 in 10 people in the United States each year—

The “spices kill bugs” hypothesis emerged from extensive observations and analyses. It has generated several predictions that have been tested.

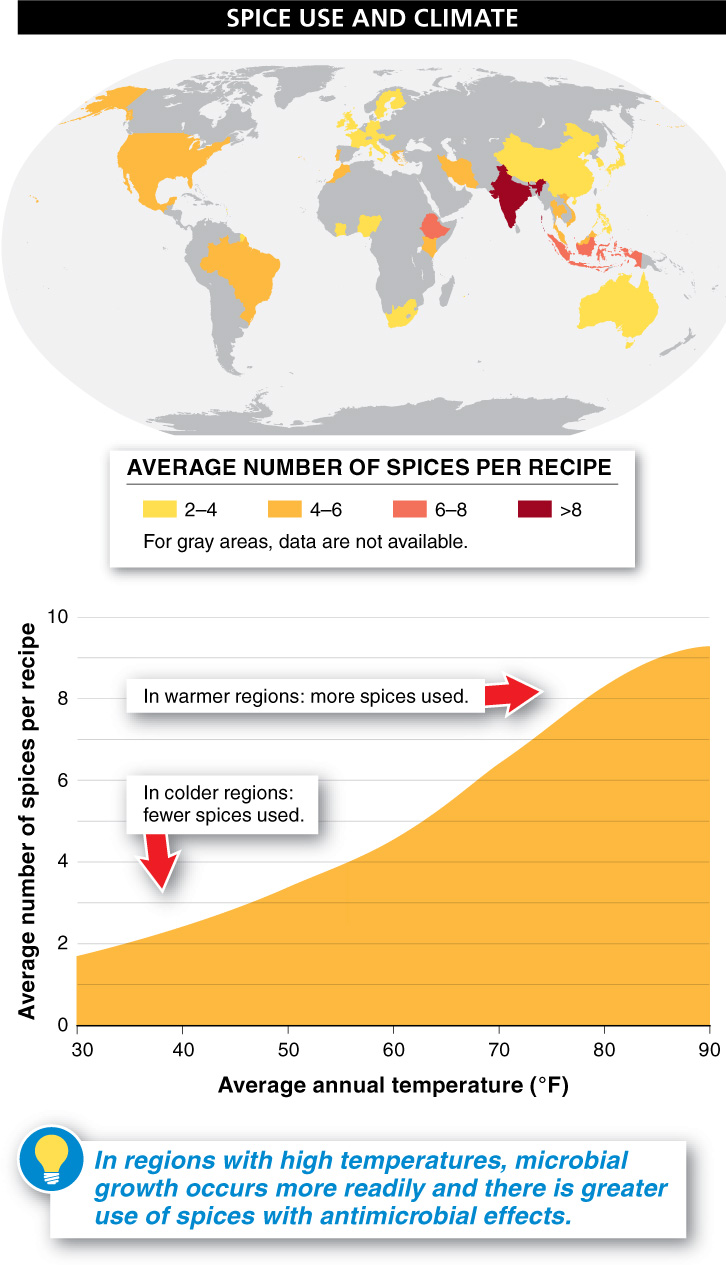

Prediction 1: The magnitude of spice use in any part of the world should be related to the amount of microbial growth in that part of the world.

Observations: Put another way, this is a prediction that in warm, wet countries (where microbial growth occurs more readily), spice use should be greater, while in cooler climates, spice use should be less. In an analysis of morethan 4,500 meat-

909

Two observations suggest that this relationship between spice use and climate cannot be attributed to the fact that more spices grow in the countries with hotter, wetter climates. First, onion and garlic, two of the most potent antimicrobial spices, grow in all of the countries studied but are used more frequently in the warmer countries. And second, although the warmer countries do have larger numbers of local spices to choose from, they use a greater proportion of the available spices than do the cooler countries.

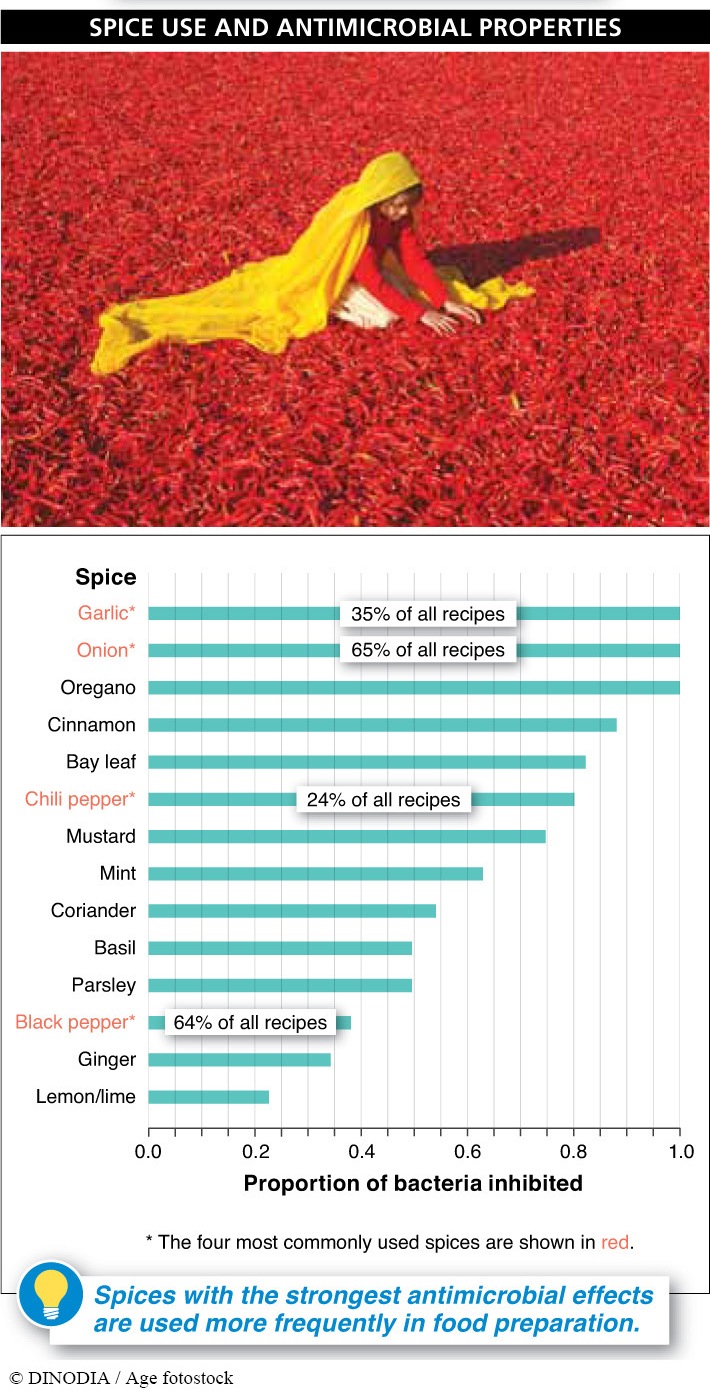

Prediction 2: Spices with the strongest antimicrobial effects should be used most frequently, and the weaker antimicrobial agents used less frequently.

Observations: In a test of 42 spices, in which each was added to individual plates of bacteria, nearly all exhibited antimicrobial properties—

Prediction 3: Because bacterial growth is faster and more common on meat than on vegetables, meat recipes should call for more spices than vegetable recipes.

Observations: The vegetable recipes called for, on average, 2.4 spices, while the meat recipes called for almost twice as many, with an average of 3.9.

Research on the connection between the use of spices and their antimicrobial properties continues. Current research focuses on evaluating the minimum spice concentrations that are necessary for inhibitory activity. After all, it’s not helpful if the amount of a spice required to have an antibiotic effect is much greater than the amount typically used. Additionally, it is important to evaluate the specific bacterial species inhibited by each spice in order to determine the real-

Nonetheless, the observations above are consistent with the suggestion that humans may have initially incorporated spices into food preparation because of their antimicrobial properties. And this example shows how seemingly arbitrary behaviors may reflect evolutionary adaptations.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 22.19

Plants produce toxic compounds that make the plant distasteful to would-

In general, how does spice use correlate to climate?

Countries with high average temperatures, which can promote bacterial growth, tend to use spices much more extensively than countries with lower average temperatures and conditions less hospitable for bacterial growth.

910