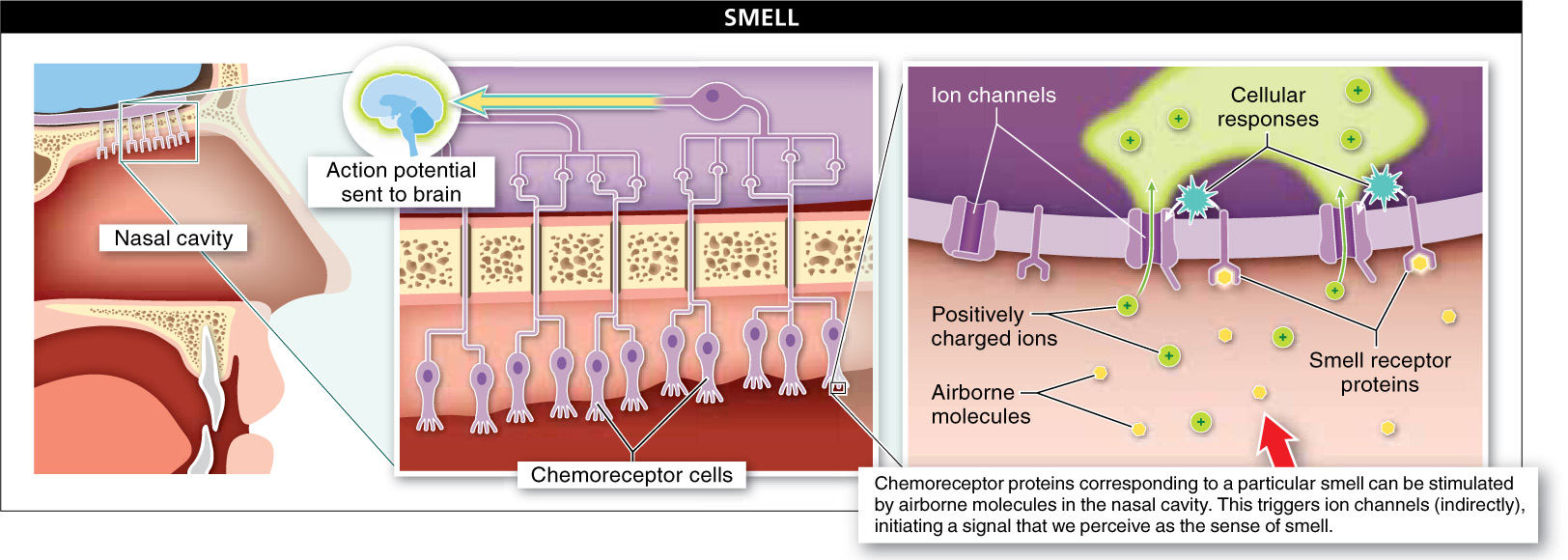

Our sense of smell works in almost exactly the same way as our sense of taste. Neurons that can detect smells have dendrites modified with tiny, hair-

Why are your senses of smell and taste dulled when you have a cold?

In humans, the senses of smell and taste are closely connected, because the air in the mouth, throat, and nasal passages circulates around all these areas. You may have noticed that when you have a cold and your nose is stuffed up, you taste little beyond the basic salt, sweet, bitter, and sour tastes on your tongue, and you can’t smell anything at all. Your senses of taste and smell are dulled because increased mucus in your nasal passages reduces the rate at which airborne chemicals can reach the smell receptors and taste receptors on dendrites in your nose and on your tongue.

935

Animals vary greatly in their sensitivity to smells, and humans don’t fare too well in the competition. Recent evidence even suggests that fewer and fewer of the genes coding for the different smell receptors in humans function properly any more. Interestingly, human females are significantly better than males at detecting, distinguishing, and identifying odors, a sensitivity that is even greater during the days surrounding ovulation.

People are much worse than dogs at sniffing out drugs. Why?

Dogs are among the most smell-

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 23.10

Neurons that can detect smells have dendrites modified with tiny, hair-

Are the numbers of different types of smell receptors similar to the numbers of different taste receptors?

No, not at all. There are only five groups of taste receptors; however, there are over a thousand different smell receptors in the human nose, each capable of detecting a different scent.

936