Stimulation of the reward centers in the brain spurs animals to behave in certain ways. We’re built this way on purpose: when we behave in ways important to our evolutionary fitness, our brain releases neurotransmitters such as dopamine. Exposed to such neurotransmitters, our pleasure centers produce the sensation of bliss. And that bliss spurs us to seek out that feeling again once it fades. Usually this system works well.

Our brain’s signaling system can be tricked, however, and with potentially disastrous consequences. Drugs—

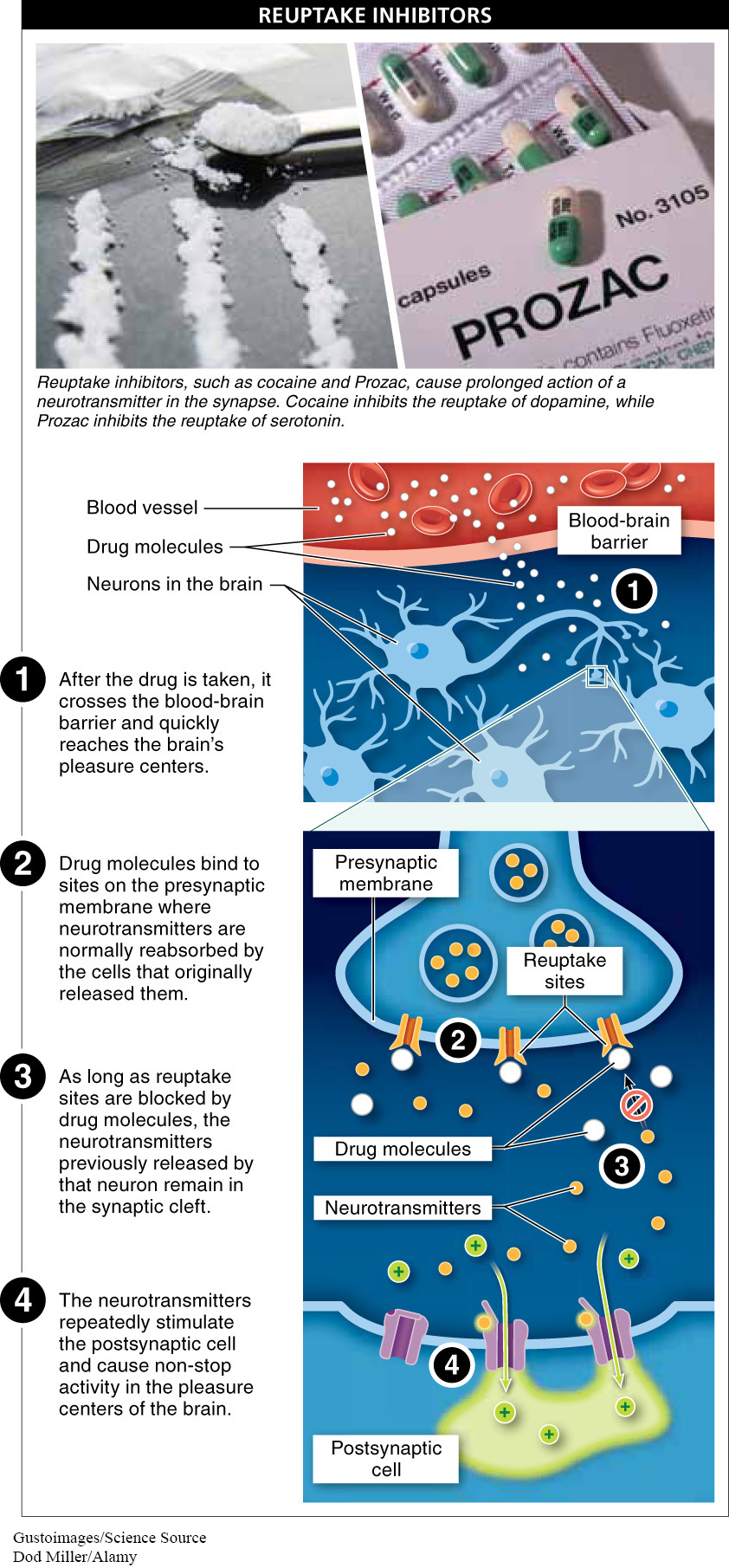

Cocaine When someone snorts a bit of cocaine, it crosses the blood-

Prozac and Zoloft Antidepressants work by a mechanism almost identical to that of cocaine. In addition to dopamine, another neurotransmitter important in our brain’s pleasure centers is serotonin. The antidepressants Prozac and Zoloft block serotonin from being reabsorbed and recycled by the presynaptic cells that released it, prolonging its effect (see Figure 23-47). This is why these drugs are called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). The net result is that people taking these medications generally experience an elevated mood because of serotonin’s prolonged stay in the synaptic cleft.

Morphine and Heroin Some chemical messengers we ought to be especially thankful for are the endorphins, our body’s natural painkillers. Produced by our brain, endorphins block pain messages arriving from throughout the body. Under a variety of situations of extreme stress—

The popular opiates morphine and heroin mimic endorphins and bind to their receptor sites. With a large enough dose, opiate users can give themselves an “endorphin rush” and feelings of euphoria far more intense than anything possible with their own natural supply of these pleasure compounds. The respiratory slowdown that comes with heroin use can occur quickly and, with large doses of heroin, can be fatal.

958

Nicotine One of the most commonly used drugs is nicotine. Shortly after entering the bloodstream, nicotine begins mimicking one of the body’s most common and important neurotransmitters: acetylcholine. Fooled by the nicotine binding to acetylcholine receptors, cells release adrenaline and other stimulating chemicals, including pleasure-

When we consume drugs such as those described above, our bodies soon respond to the perception that there are larger amounts than usual of certain neurotransmitters. Usually the response is a reduction in sensitivity to the drug. Although tolerance is inevitable, its magnitude and consequences vary with the type of drug. In one study, volunteers were injected with a uniform daily dose of heroin and monitored for their level of euphoria. Initially they were ecstatic, but their bodies reacted by reducing the number of receptors that bind heroin. With fewer and fewer receptors, the euphoric heroin effects dropped almost to zero in just three weeks. Similar changes occur in response to using caffeine, nicotine, or alcohol.

Can a gene nudge you toward risk-

Do human drug addictions and dependencies reflect differences in our genes? Recent data suggest that they might at least be influenced by the alleles a person carries. In one study of 283 individuals, a third of the people who smoked had a version (i.e., an allele) of an important gene that almost none of the non-

959

In the next section we look at a popular and effective drug that acts, not by blocking neurotransmitter reuptake, but rather by blocking the postsynaptic receptors.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 23.20

Our brain’s signaling system can be tricked by drugs, whether recreational or therapeutic, that mimic neurotransmitters. Such drugs—

What are SSRIs, and what effect do they have on neurotransmitters?

SSRI stands for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. SSRIs, such as Prozac and Zoloft, block serotonin from being reabsorbed and recycled by the presynaptic cells. The net result is that people taking these drugs generally experience an elevated mood because of the neurotransmitter's prolonged stay in the synaptic cleft.