“Trust me.” It’s easy enough to say, but can be very difficult to do. Recently, however, some researchers discovered a way to actually make people more trusting. Here’s how they did it.

Study participants, called investors, were given an amount of money. Each investor could keep the money or transfer some or all of it to another person, called a trustee. Any amount the investor chose to transfer to the trustee was tripled: the trustee could then return to the investor some portion of the significantly increased pot of cash, or the trustee could simply keep it all. For the investors, this created a dilemma—

Using a double-

The results were dramatic and unambiguous. The oxytocin group was significantly more trusting than the placebo group: more than twice as many of those receiving oxytocin entrusted the maximum amount of their money to the trustee, compared with investors who did not inhale oxytocin. And more than twice as many of those in the placebo group as in the oxytocin group transferred the smallest amounts of cash to the trustee, apparently exhibiting a greater fear of betrayal.

This result is consistent with some findings of research on other animals. In those studies, exposure to oxytocin reliably caused animals to let down their guard, initiate interaction, and form social attachments with other individuals at a much higher rate than they typically would. It appears that this chemical had a similar effect on humans in the investor-

One particularly clever and valuable feature of this study’s experimental design is that in a follow-

Researchers believe that these findings give some insight into the biological basis for trust, which might even lead to effective treatments for people with extreme shyness. And the results provide a pretty clear demonstration that complex emotions and behaviors can be influenced by chemical signals produced in the body.

971

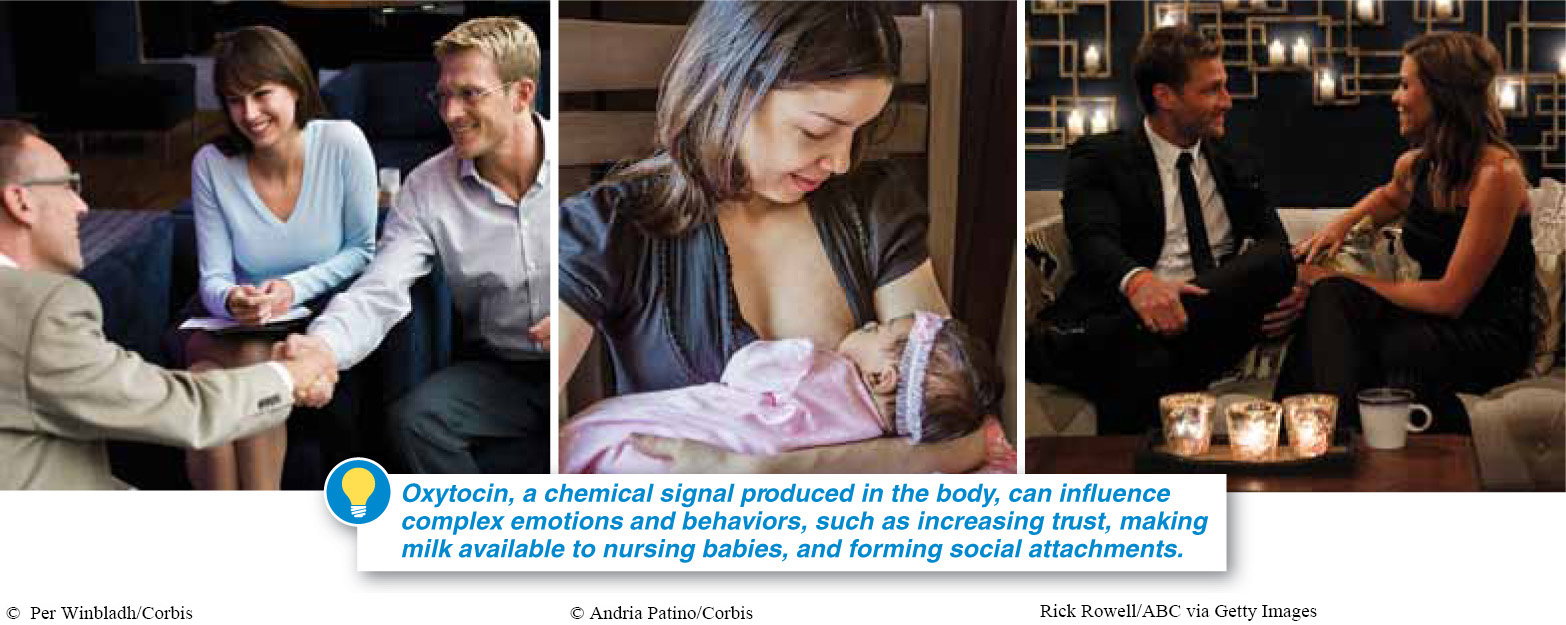

It is important to note that oxytocin influences much, much more in humans than a propensity for trust (FIGURE 24-1). Research has demonstrated that oxytocin plays significant roles in making milk available to nursing babies and in facilitating birth. In fact, the name “oxytocin” is from the Greek word meaning “quick birth,” based on the recognition of its role in stimulating uterine contractions. Since oxytocin has also been shown, as noted above, to increase the propensity to form social attachments, some researchers refer to it as the “cuddle drug.”

In this chapter, we see that oxytocin is just one of several dozen influential chemical signals in vertebrates and many other eukaryotes. We explore just what these chemicals are, where they are produced, and how they have their effects. We also explore their pervasive influence in nearly every aspect of vertebrate life, from emotions to physical structures, behavior, and health and physiology.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 24.1

Complex emotions and behaviors can be influenced by chemical signals produced in the body. For example, exposure to oxytocin causes humans to be more trusting of others, as well as facilitating birth, making milk available to nursing babies, and increasing the propensity to form social attachments.

In the oxytocin/trust experiment described in the text, why didn't the researchers give oxytocin to all of the study participants?

The subjects that received a placebo instead of the oxytocin formed the control group. When researchers compared the results from the experimental group (those receiving the oxytocin) to those from the control group, they noted that people in the experimental group were more trusting than those in the control group. This difference was attributed to the variable in the experiment: the presence of oxytocin.