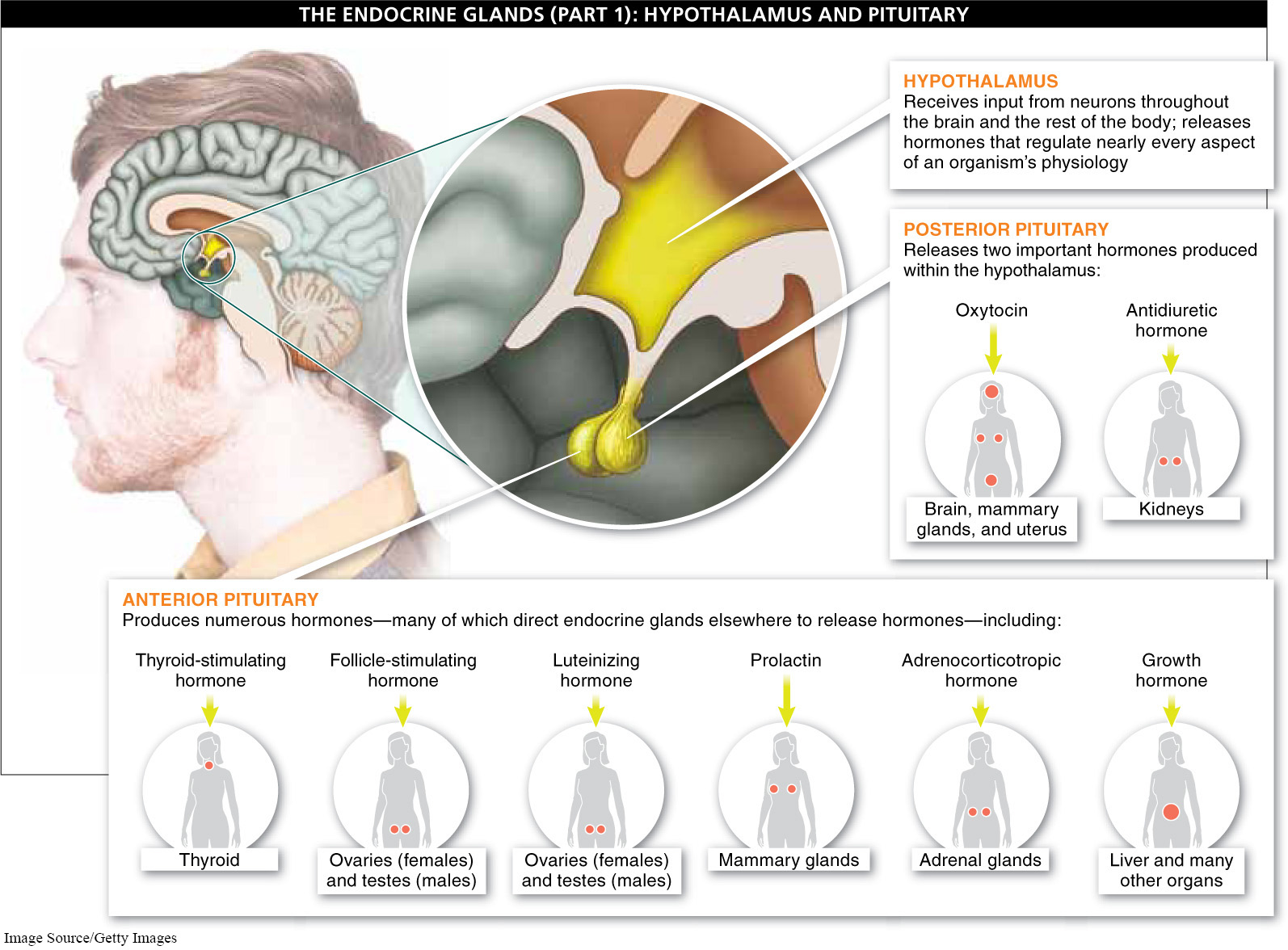

As we have seen, animals have both the nervous and endocrine systems to send signals and regulate body functions in response to their external environment. And although one system or the other tends to be more effective for particular tasks, there is considerable interaction between the two. The hypothalamus, part of the underside of the brain, functions as a liaison between the nervous and endocrine systems, and it receives input from neurons throughout the brain and the rest of the body (FIGURE 24-7). Using this information about the external environment and the physiological state of the body, the hypothalamus sends out the appropriate hormones (and nervous signals) to regulate nearly every aspect of the organism’s physiology, including body temperature, hunger, thirst, and water balance.

Attached to the hypothalamus by a thin stalk is a gland about the size of a pea, called the pituitary gland. Signals from the hypothalamus directly influence the pituitary gland. The hypothalamus may release hormones that cause the pituitary to increase its production and release of hormones. Or the hypothalamus may direct the pituitary to reduce or stop the release of hormones.

The pituitary gland is actually two separate glands fused together. The two regions look different, originate from different embryonic tissues, produce different hormones, and are regulated differently. We will consider the two regions separately.

The posterior pituitary has a fibrous appearance, because it contains a large amount of nervous tissue, particularly axons coming straight from the hypothalamus—

- 1. Oxytocin, the “cuddle hormone,” discussed in Section 24-

1 , influences people’s trust in others and increases the propensity to form social attachments, as well as directing the ejection (or “let-down”) of milk for nursing babies and stimulating muscle contractions in the uterus during childbirth. - 2. Antidiuretic hormone (ADH) influences water retention by the kidneys. With increased levels of ADH, more water is saved, reducing the amount of urine produced while increasing its concentration.

The anterior pituitary has a more glandular appearance than the posterior pituitary: it develops from epithelial cells near the roof of the mouth during embryonic development. The anterior pituitary produces numerous hormones in response to commands by the hypothalamus. Many of the anterior pituitary hormones direct endocrine glands elsewhere to release hormones. Some of the most important hormones produced by the anterior pituitary in mammals include the following:

977

- 1. Thyroid-

stimulating hormone (TSH) causes the thyroid to produce thyroxine, important in cellular respiration, which we discuss further in Section 24-5 . - 2. Follicle-

stimulating hormone (FSH) stimulates follicles in the ovaries to begin development, and luteinizing hormone (LH) triggers ovulation. In males, FSH stimulates sperm maturation and LH stimulates testosterone production. - 3. Prolactin stimulates the mammary glands to produce milk.

- 4. Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), also known as corticotropin, stimulates the adrenal glands to produce cortisol and other stress-

related hormones. - 5. Growth hormone has several effects, including stimulating the liver to release chemicals that spur the growth of bones, cartilage, and many other tissues.

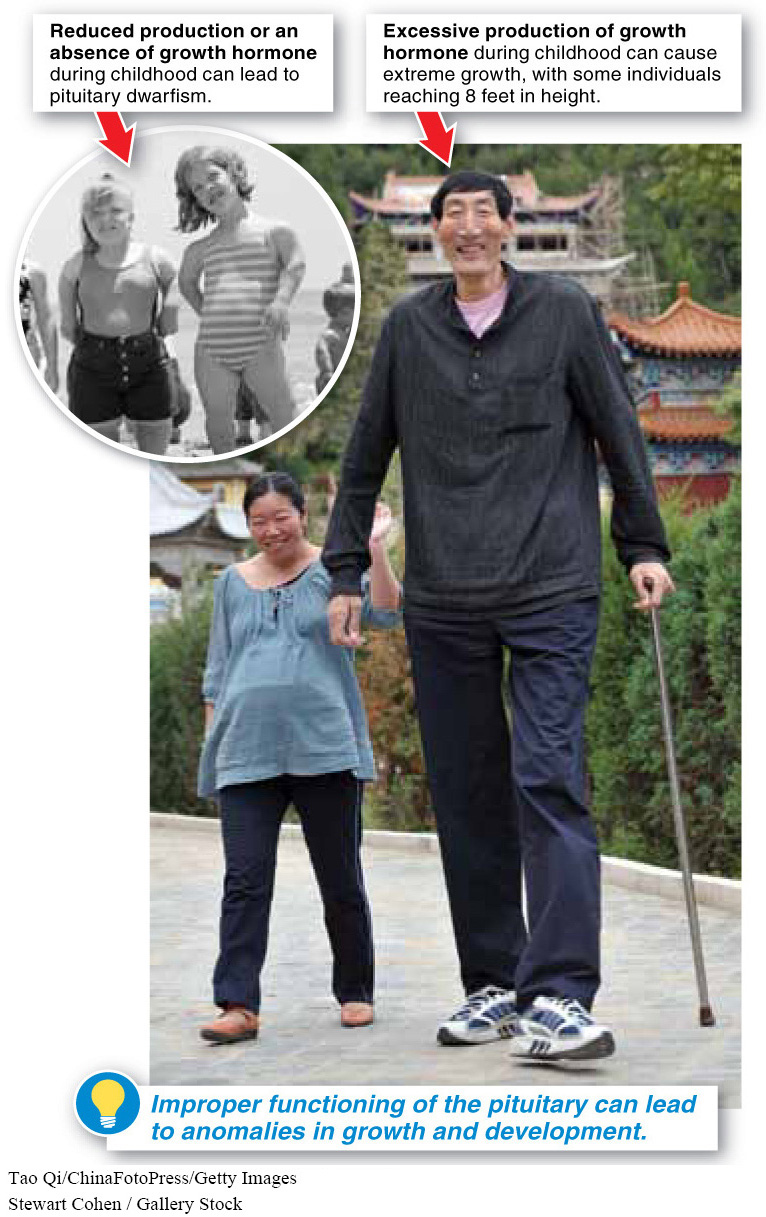

Improper functioning of the pituitary can lead to some anomalies in growth and development. Excessive production of growth hormone during childhood, for example, can cause extreme growth, called gigantism, with some individuals reaching 8 feet in height (FIGURE 24-8). If the increased exposure to growth hormone doesn’t occur until adulthood, only the hands, face, and feet tend to respond with unusual growth. Similarly, individuals with reduced or no production of growth hormone during childhood develop a condition called pituitary dwarfism, and may not grow more than 4 feet tall. Early diagnosis of this condition and treatment with human growth hormone can restore normal growth. See Section 5-

978

Although the hypothalamus and pituitary gland control much of the hormone secretion in the body, there are several other endocrine glands with important regulatory roles, which we explore in the sections that follow. It is also important to keep in mind that the hypothalamus and pituitary don’t necessarily control all of the hormone secretions; they themselves are regulated, in large part by the glands that they regulate, through numerous feedback loops. (See Section 20-

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 24.4

The hypothalamus receives input from neurons throughout the brain and the rest of the body, and using this information about the internal and external environments, it sends out the appropriate hormones (and nervous signals), often directing the pituitary gland to release hormones with important regulatory effects on body tissues.

List two hormones secreted from the posterior pituitary and five hormones secreted from the anterior pituitary.

Oxytocin and antidiuretic hormone (ADH) are secreted from the posterior pituitary. Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), prolactin, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and growth hormone are secreted from the anterior pituitary.