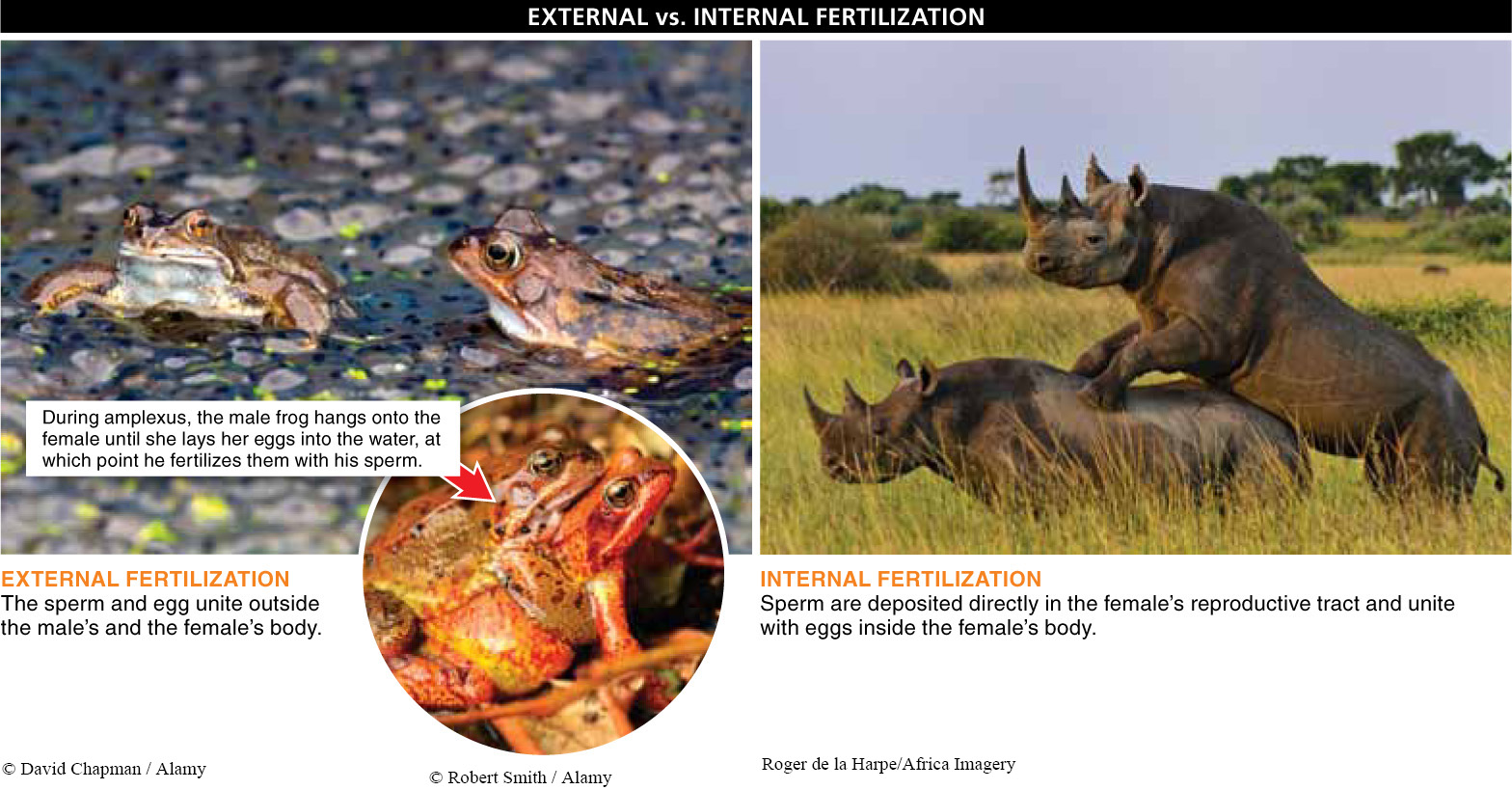

Sexual reproduction, as we’ve seen, can have evolutionary advantages. But because it requires male and female gametes to come together at fertilization, it also presents a challenge: the male and female gametes must somehow get to each other. Two general strategies have evolved as a consequence: external fertilization, in which the sperm and eggs unite outside the male’s and female’s bodies, and internal fertilization, in which the sperm are deposited directly in the female’s reproductive tract and unite with eggs inside her body (FIGURE 25-5).

The first vertebrates evolved in the oceans, where it was possible for females to release batches of eggs right into the water. Males could then release sperm into the water, and fertilization could take place. Many aquatic invertebrates—

1008

Although seawater is not harmful to sperm or eggs, one potential problem for organisms using external fertilization is that the tiny gametes of one sex can be very quickly washed away from those of the other sex. For this reason, the males and females of a species tend to produce very large numbers of gametes and release them, at the same time, very near each other. A variety of cues help synchronize their release of gametes, including water temperature, phase of the moon, day length, chemicals (pheromones) released by one or the other sex, and courtship rituals.

Some male frogs clutch onto female frogs for months at a time without letting go. Why?

Among the most extreme tactics employed for ensuring that sperm and eggs are released at the same time and in the same place is something called amplexus, used by most species of frogs. In amplexus, the male embraces the female from behind, wrapping his front legs around her. He holds on until she releases her eggs, at which point he releases his sperm to fertilize them (externally). This doesn’t sound all that remarkable, except that males will sometimes hold on to a female for weeks or even months at a time!

As we learned in Chapter 11, vertebrates’ colonization of land opened up a huge number of new niches but presented one huge problem. External fertilization just doesn’t work well on land. First, gametes cannot be moved around (and thus toward each other) without water. Second, and even more important, gametes quickly dry out. For these reasons, there was strong selective pressure on land-

Used by nearly all terrestrial animals, internal fertilization solves the problem of gamete desiccation (drying out) by having males deposit their sperm directly inside the females. This deposit is usually accomplished by the male placing his reproductive organ within the female’s reproductive tract, in the act of copulation. Inside the female’s body, there is sufficient moisture for the sperm to remain viable until fertilization can occur.

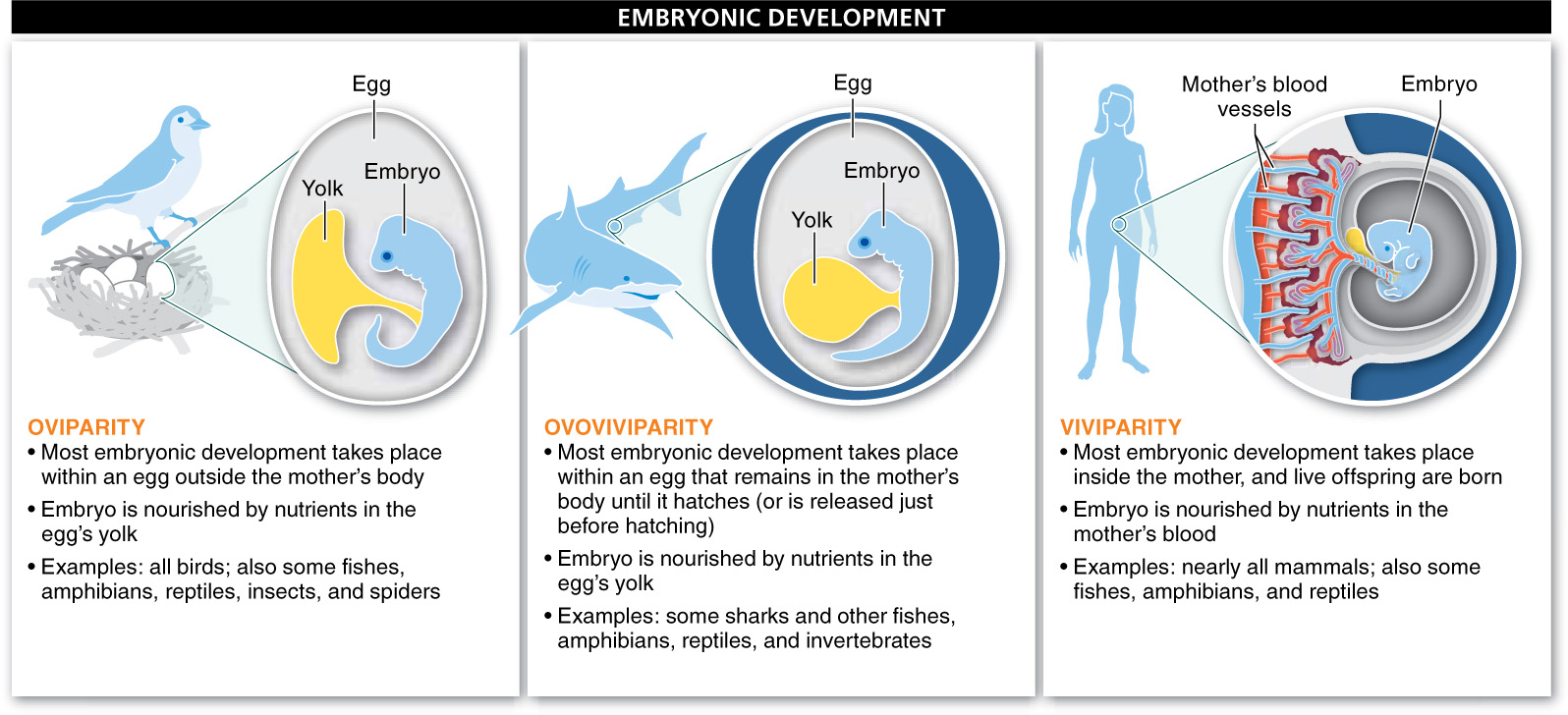

Once an egg is fertilized by a sperm, the fertilized egg is called a zygote. Following the first division into two cells (and continuing until approximately 8 weeks of development in humans), it is called an embryo. The offspring must, at some point in its development, leave the female’s body. There are three different strategies for this (FIGURE 25-6).

1. Oviparity, a strategy in which the fertilized egg moves outside the body, where most embryonic development continues. The embryos are nourished by nutrients in the egg’s yolk, and live offspring emerge from the egg. This developmental strategy is most familiar to us among birds (all bird species are oviparous), but it also occurs among most fishes, amphibians, reptiles, insects, and spiders.

1009

2. Ovoviviparity, a less common strategy, in which most embryonic development takes place inside an egg, with the embryo nourished by the egg’s yolk, but the egg itself remains in the female’s body until it hatches (or is released just before hatching). This strategy is used by many aquatic organisms, including sharks and some other fishes, and by some species of amphibians, reptiles, and invertebrates.

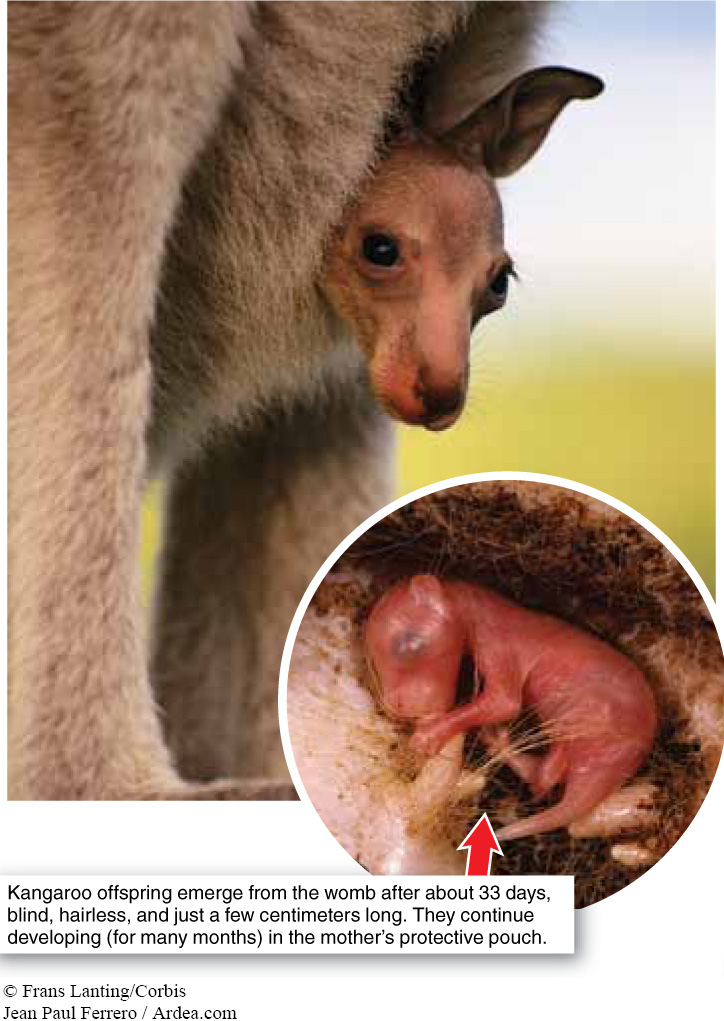

3. Viviparity, a strategy in which the embryo develops inside the mother, nourished by nutrients in her blood, and live offspring are born. This strategy is perhaps most familiar because it is used by humans and nearly all other mammals (including marsupials; FIGURE 25-7), but it also occurs among some reptiles, amphibians, and fishes.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 25.3

Sexual reproduction requires fertilization, which occurs externally in most fishes and amphibians and internally in most other vertebrates, including humans. Among those species having internal fertilization, development of the embryo can be nourished by yolk within an egg (that may or may not be retained within the female’s body during development) or, remaining in the mother’s body, by nutrients in her blood.

What selective pressures led to the evolution of internal fertilization in land-

External fertilization remained tied to water; gametes were unable to move around without water and quickly dried out on land. Internal fertilization avoided these problems.

1010