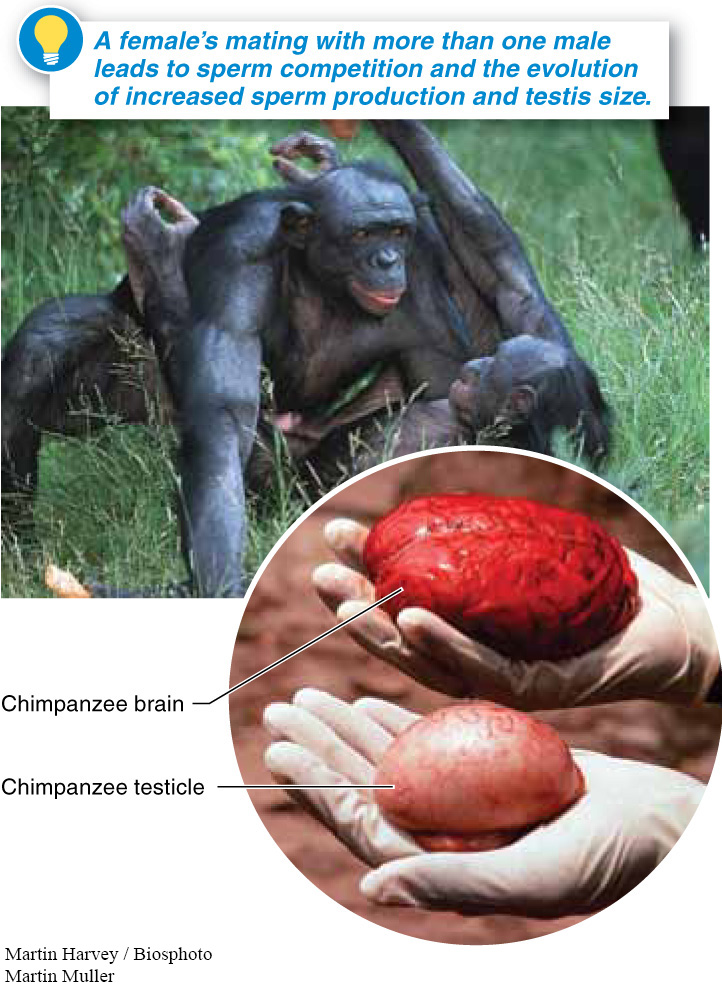

In The Chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of Behavior, Jane Goodall reported female copulatory rates of “an average of between five and six copulations per female per hour in the early morning, after which the rate dropped gradually to about two per hour in the midmorning, rose very slightly during the afternoon, and tapered off to one per hour in the evening.” These observations were relevant to the realization reached by earlier researchers that if females (of any species, not just chimps) mate with more than one male, there may be competition among the males’ sperm.

A chimp’s testicles are 15 times bigger, relative to body weight, than a gorilla’s! Why?

The idea of sperm competition, or “sperm wars” as this has been called, gives rise to several testable predictions. One simple prediction is this: when a female is likely to mate with more than one male, the males that produce more sperm are more likely to be successful at fertilizing the female’s eggs. Some interesting observations support this prediction. For example, gorillas have golf-

Sperm competition has given rise to several other adaptations.

Physical barriers to copulation, such as the mating plugs produced in many species (including some squirrels, mice, scorpions, and spiders) by the coagulation of semen, which prevent other males’ sperm from entering the female’s reproductive tract.

- Q

Why do male fruit flies produce toxic semen?

Toxic semen components, such as the protein in fruit fly semen that suppresses further mating by the female for several days (ensuring a male’s paternity), as well as other fruit fly semen components that can incapacitate the sperm of other males (and even decrease the female’s lifespan by about 10%).

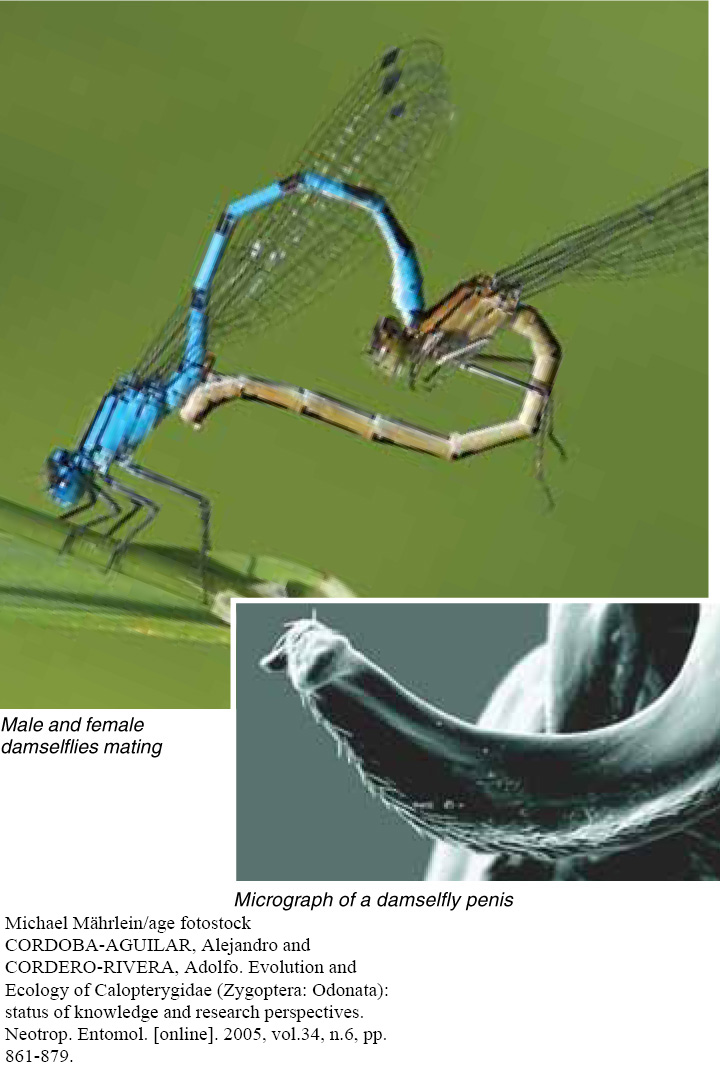

Genital morphology, such as the claspers and scrapers of dung flies, as well as the “shovel penis” of some dragonfly species that makes it possible for males to dislodge the sperm of other males that have already mated with a female (FIGURE 25-13).

1014

This unseen conflict between males is an area of considerable investigation, as researchers try to understand the physical and behavioral consequences of such competition. And females are not passive players in these battles; research studies have documented how, in many cases, a female will eject the sperm from undesirable males.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 25.5

When females mate with more than one male, sperm competition occurs and can lead to a variety of adaptations, including increased sperm production and testis size, semen that can create a physical barrier to subsequent mating, toxic semen components, and penis morphology that aids in the displacement of rival males’ sperm.

What predictions can you make if the males of a species have testes that account for a relatively large percentage of their body weight?

A large testicular mass-to-body mass ratio is generally indicative of a mating strategy in which females copulate with multiple males.