As we’ve seen, in a population of animals, when a female typically mates with more than one male, sperm competition occurs. This can result in the evolution of increased sperm production and testis size—

But what impact does sperm competition have on the individual male? Some researchers explored this question, beginning with the hypothesis that “males respond to a risk of sperm competition with increased sperm investment.”

Is this a testable hypothesis? How might we test it?

Like many hypotheses, this one may be a bit too broad. For example, it doesn’t identify any particular species, or what qualifies as a “risk of sperm competition.” In addition, for a hypothesis to be useful, it must be falsifiable. But it may be difficult to determine whether males are unable to respond to the risk of sperm competition with increased sperm investment, or whether males are able to respond, but simply do not perceive a risk of sperm competition.

These potential difficulties don’t make it impossible to address the hypothesis. Rather, they are issues to keep in mind when modifying the hypothesis and considering how to test it—

1015

What is a good rule of thumb when crafting a hypothesis that will be testable?

Keep it simple. That is, try to control for as many potential sources of variation in the measure of interest—

How could you control for the potential issue of male-

Controlling for differences among individuals (for a variety of traits) is a common goal when designing an experiment. An effective way to do this is to use a large number of individuals, and to test each individual in two different situations. In other words, it is probably not ideal to measure one group of males for sperm investment when there is a risk of sperm competition and to measure another group of males for sperm investment when there is no risk of sperm competition. It’s better to use a single group of males and to test each male under both conditions. That way, regardless of whether a male has relatively high or low sperm investment (compared with other males), we can determine whether his sperm investment is increased when there is a risk of sperm competition. And that’s the effect we’re interested in.

Some researchers took this approach as they set out to test this idea. First, they made a couple of additional refinements to the hypothesis, and thus to how they would test it. They decided to limit their study to one species—

Their experimental approach was simple and straightforward.

The set-

Ten males were used. Five were randomly assigned to the control context first, and then, 30 days later, to the RSC context. The other five were assigned to the RSC context first and, 30 days later, to the control context. This set-

The measurements When the mating was completed, the researchers collected all of the semen from the female vole’s reproductive tract, and determined the male’s sperm investment—

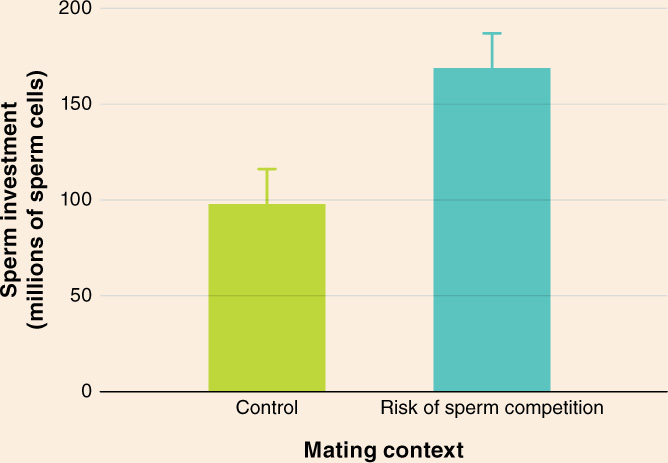

The results In all 10 voles, the sperm investment was greater in the RSC context. The average sperm investment in the control context was 98 (±18) million sperm, and in the RSC context was 169 (±18) million sperm—

What other data might help evaluate the researchers’ hypothesis?

In a subsequent experiment, the researchers found there was no increase in sperm investment when the male voles were exposed to the odors of males from another species. Why does using the odor of another species serve as a type of control in this study?

1016

What can you conclude from these results?

The researchers concluded that male mammals may increase their sperm investment in response to an odor from another male of the same species. Could an individual’s ability to alter his sperm investment in response to chemical cues in his environment have adaptive value? How might you explore this question further?

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 25.6

Male voles respond to a risk of sperm competition with increased sperm investment. This physiological response can be triggered by odors present in the urine and feces of other males of the species.

Based on the study results, if males of a different species of vole were present, would you expect to see increased sperm investment in the male meadow voles? Why or why not?

Based on the study results, there would not be increased sperm investment on the part of male meadow voles if males of a different species were present. In the follow up study, researchers found there was no increase in sperm investment when male meadow voles were exposed to the odors of males from another vole species. Although this would need to be scientifically investigated further, it seems likely that meadow voles are able to discriminate between males of their own species and males of other species.