The specific immune response, as we saw in Section 26-

1. Cytotoxic T cells are the effectors (the first responders) of the cell-

2. Helper T cells do not directly kill infected cells, but, instead, stimulate other immune cells. Helper T cells stimulate B cells to produce antibodies and cytotoxic T cells to kill infected cells.

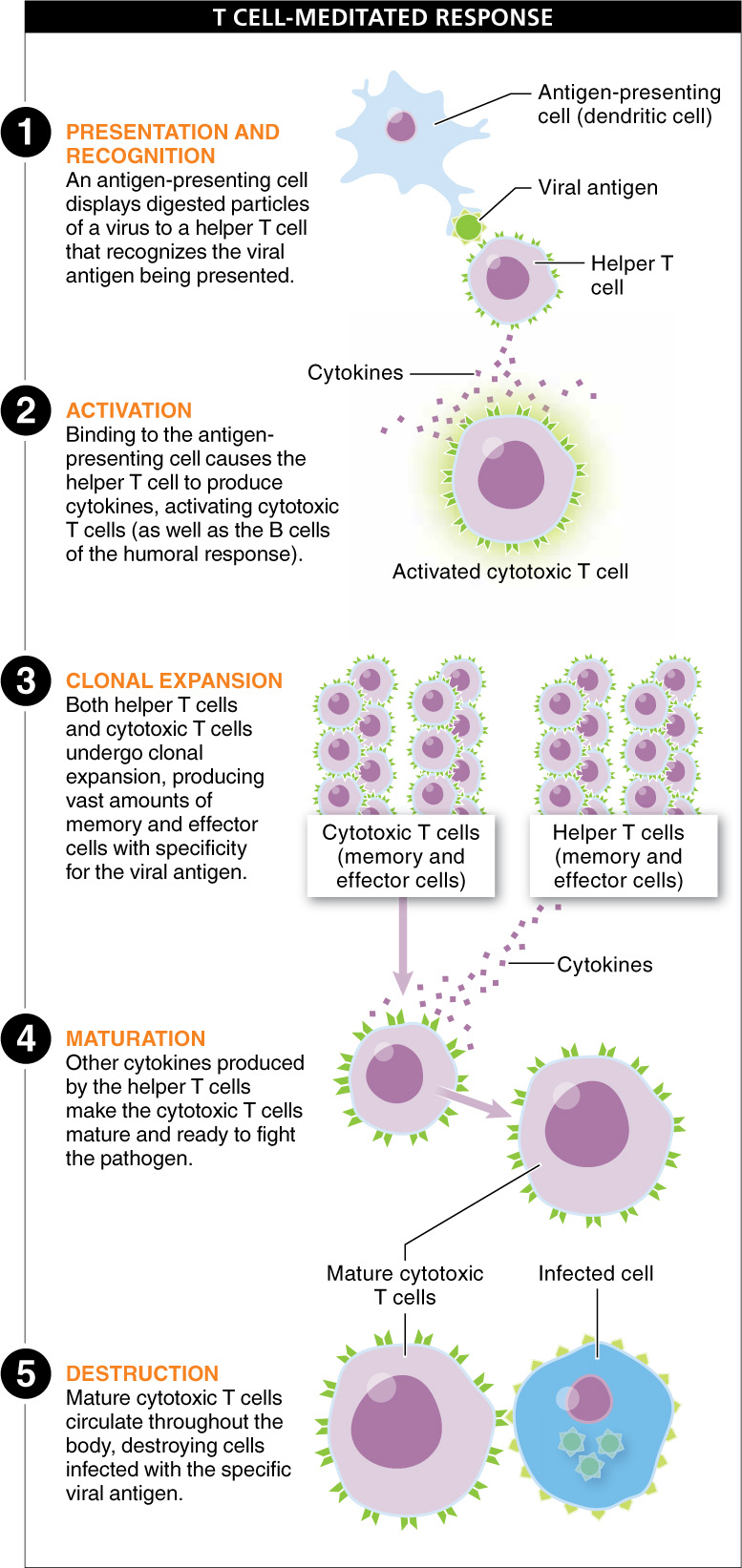

We’ll follow a viral infection through the cell-

When a pathogen enters the body, the phagocytes and NK cells of the non-

Circulating through a lymph node or the spleen, a macrophage may bump into helper T cells with specificity for the viral antigen being presented on the macrophage surface. The helper T cell receptor recognizes the antigen, and the T cell locks onto the antigen-

Both helper T cells and cytotoxic T cells then undergo clonal expansion, producing vast numbers of memory and effector cells with specificity for the viral antigen. Other cytokines produced by the activated helper T cells provide the final signals that make the cytotoxic T cells “mature” and ready to fight the pathogen at the site of infection. You may notice this process occurring when you’ve been sick: the rapid division of lymphocytes in the lymph nodes causes the nodes to swell (usually called “swollen glands”). The helper T cells and cytotoxic T cells then leave the lymph nodes or spleen and circulate throughout the body. (Helper T cells also are required to stimulate B cells to produce antibodies; B cell development occurs only in response to these signals from helper T cells.)

Mature cytotoxic effector cells are like newly trained soldiers, ready to fight the enemy, but first they need to detect where the enemy is hiding. Consider a cell in the throat that is infected with a respiratory virus. Is the cell revealing that it’s under attack? Yes! The infected cell displays some of the pathogen’s molecules on its surface receptors, advertising the infection to the now numerous cytotoxic T cells that can recognize that specific respiratory virus.

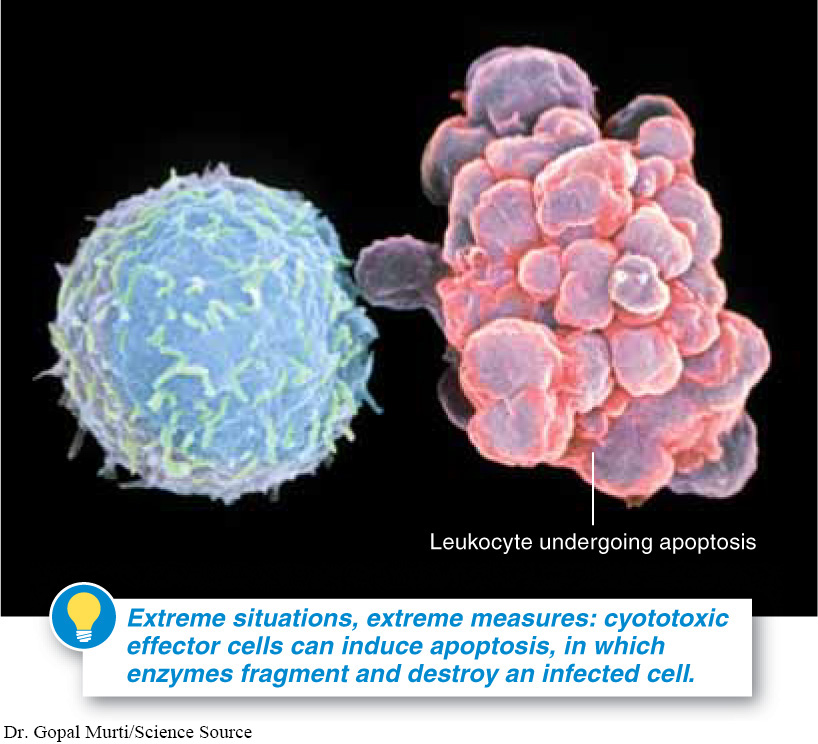

How do the cytotoxic effector cells fight the internal pathogen? They do something drastic—

1067

Because memory helper T cells and memory cytotoxic T cells are also made during an infection, this same virus cannot cause illness again. Memory cells will leap into action to make more effector cells if the virus ever returns.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 26.10

Antibodies, produced by B cells, cannot destroy pathogens that are inside cells. The specialization of cytotoxic T cells is required to kill infected cells. Antigen-

Why is antibody-

Viruses must enter cells in order to produce more viruses. Although antibodies are helpful in binding to and inactivating viruses before they infect cells, antibodies cannot reach the viruses that are already inside of cells. T cell-mediated immunity involves the direct destruction of these virally infected cells.

1068