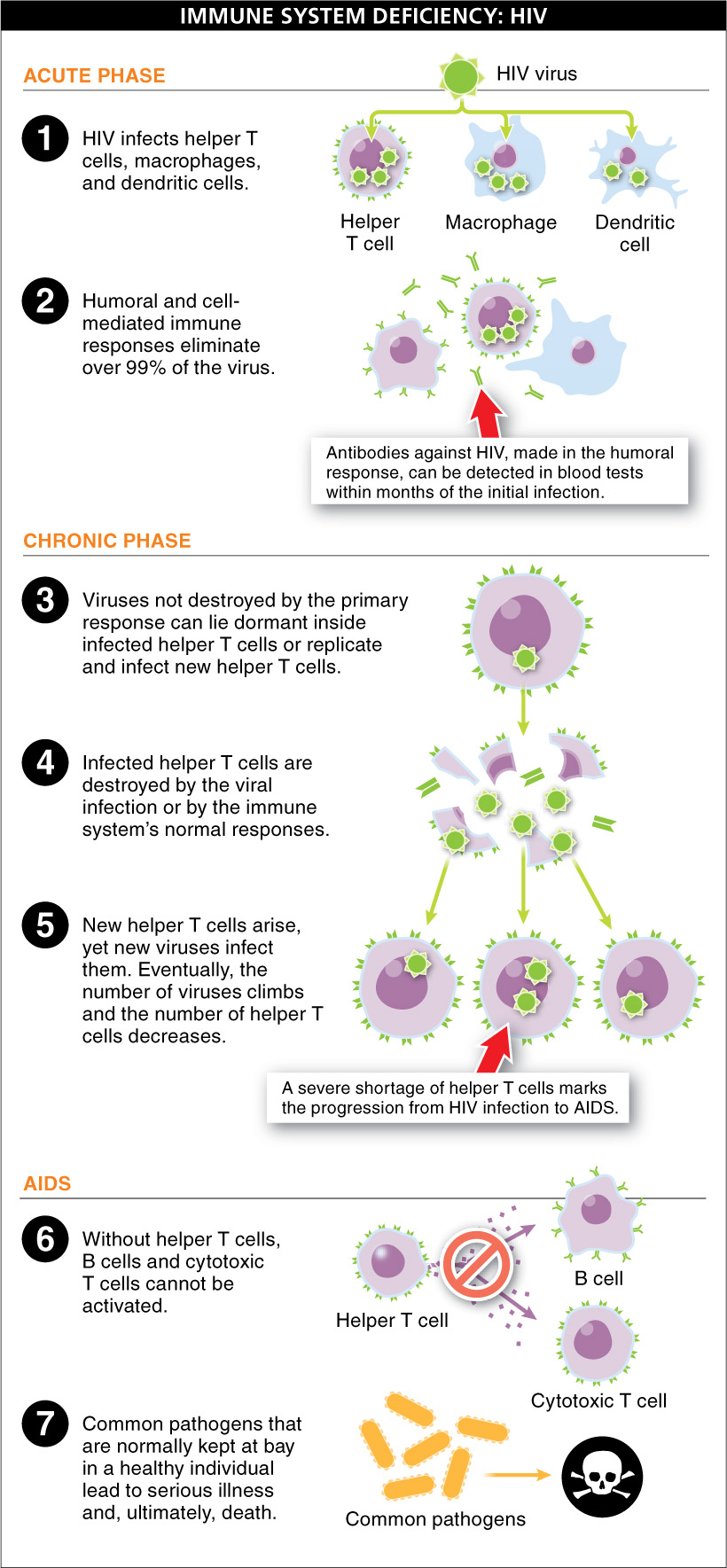

Autoimmune diseases demonstrate how immune recognition can fail and have devastating effects on the body. Here we examine a case in which recognition of a true pathogen occurs, but the response is deficient. Normally, the immune system destroys body cells that are infected with a virus. But when a virus infects immune cells, the body’s ability to respond to infection is impaired. The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which causes AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome), infects immune system cells, including helper T cells—

HIV infection occurs through contact with blood, semen, vaginal fluid, or breast milk from an infected person. Thus, using clean (not shared) intravenous needles and using condoms are effective precautionary measures against HIV infection. People who become infected with HIV often do not have immediate symptoms and often do not know they are infected. Because individuals are contagious once they are infected, this initial lack of symptoms contributes to the spread of the disease. Let’s examine the details of how immunity diminishes as the immune system loses its battle against HIV.

1070

Different viruses infect different kinds of body cells. Parvovirus B19 infects heart muscle, for example, causing an inflammation of the heart, and West Nile virus attacks brain tissue and can cause encephalitis, a dangerous inflammation of the brain. HIV, on the other hand, infects helper T cells and macrophages, among other cells. When an individual is first infected by HIV, a normal specific immune response is mounted, and infected helper T cells are killed by both humoral and cell-

Unfortunately, the viruses that were not destroyed by the primary response can lie dormant inside infected helper T cells and macrophages. The infection then enters a period called the chronic phase, in which the person is infectious but doesn’t have outward symptoms. This period is variable but rarely exceeds 12 years. Although the infection may seem inactive, a battle is going on within the immune system. Some of the HIV viruses lie dormant, but others replicate and infect new helper T cells. Helper T cells that are infected are killed by the viral infection or are destroyed by the immune system’s normal responses. New helper T cells arise, and new viruses infect them. This cycle continues, but it is not a balanced situation. Sooner or later, the number of viruses climbs and the number of helper T cells decreases, and serious clinical symptoms appear. (This process is like an army valiantly fighting a battle but ultimately running out of soldiers.)

A severe shortage of helper T cells marks the progression from HIV infection to AIDS. Without helper T cells, B cells and cytotoxic T cells cannot be activated (recall from Section 26-

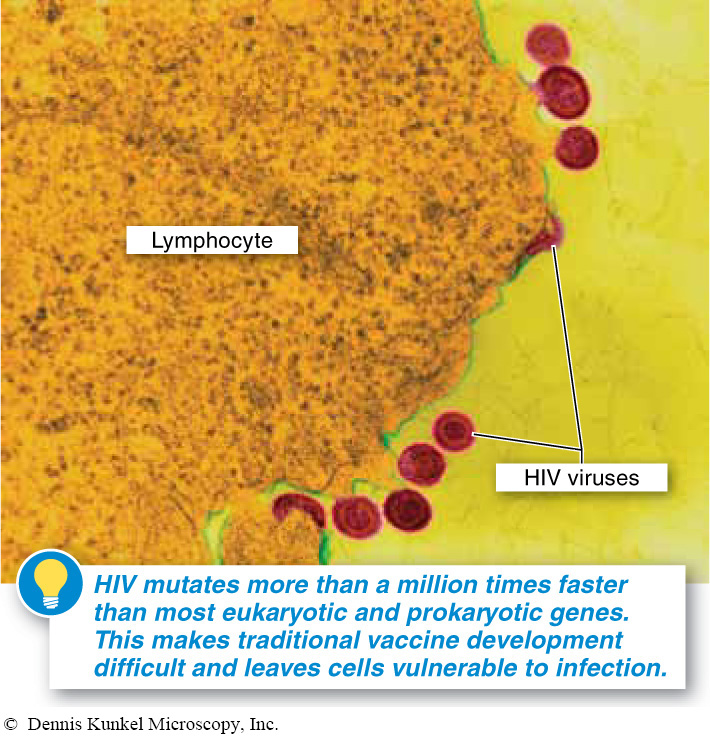

Why is there no vaccine against AIDS yet?

As we saw in Section 13-

1071

Current therapies for HIV infection have been successful at increasing the length and quality of life for those infected. The regimen, called combination therapy, includes numerous drugs that affect HIV’s ability to replicate or infect new cells. These drugs keep the number of viruses low and maintain a suitable number of helper T cells. HIV resistance to the drugs, however, is a fear shared by patients and clinicians. Nonetheless, the life span for individuals taking combination therapy is increasing and getting close to a normal length of life. Although there is not a cure yet, individuals who have access to treatment are able to live with HIV as a chronic condition. (Unfortunately, treatment is unavailable for millions of infected people in developing nations.) New therapies aim to find latent viruses that hide inside helper T cells, sometimes for decades, and eliminate them. In the future, HIV may be a disease that can be cured, but for now it continues to be a lifelong condition and a challenge to scientists.

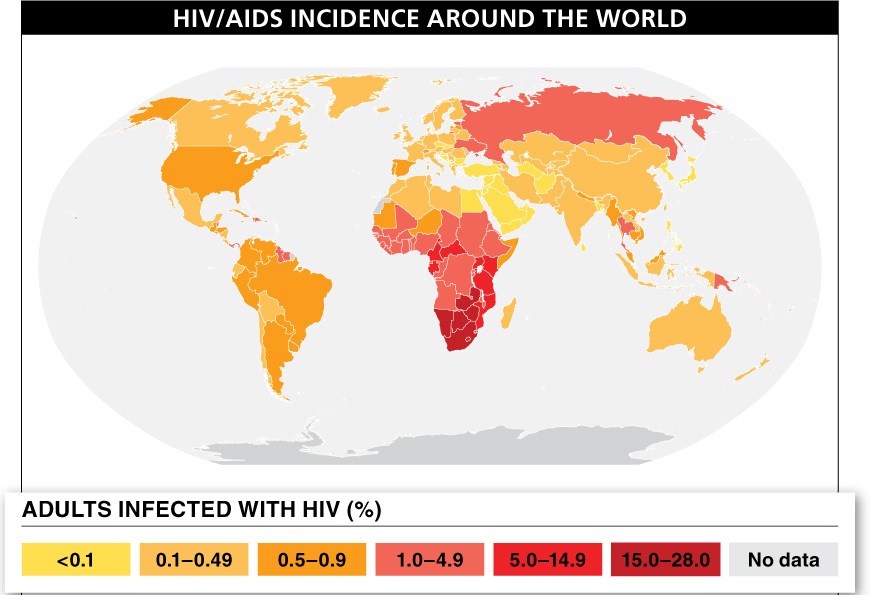

Looking at a map depicting HIV/AIDS cases around the world, we can see just how widespread this virus is (FIGURE 26-32). Sub-

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 26.12

AIDS is an immune system disease caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which infects helper T cells—

How does the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) damage or kill an infected person?

HIV infects cells of the immune system, including helper T cells. As the infection persists, the number of functional helper T cells gradually decreases. Without sufficient helper T cells, the immune system's B cells and cytotoxic T cells cannot be activated. In the absence of a functional immune system, common pathogens that are easily defeated by a healthy immune system cause serious illness and death.

1072