Often, a pathogen can be eliminated completely by the non-

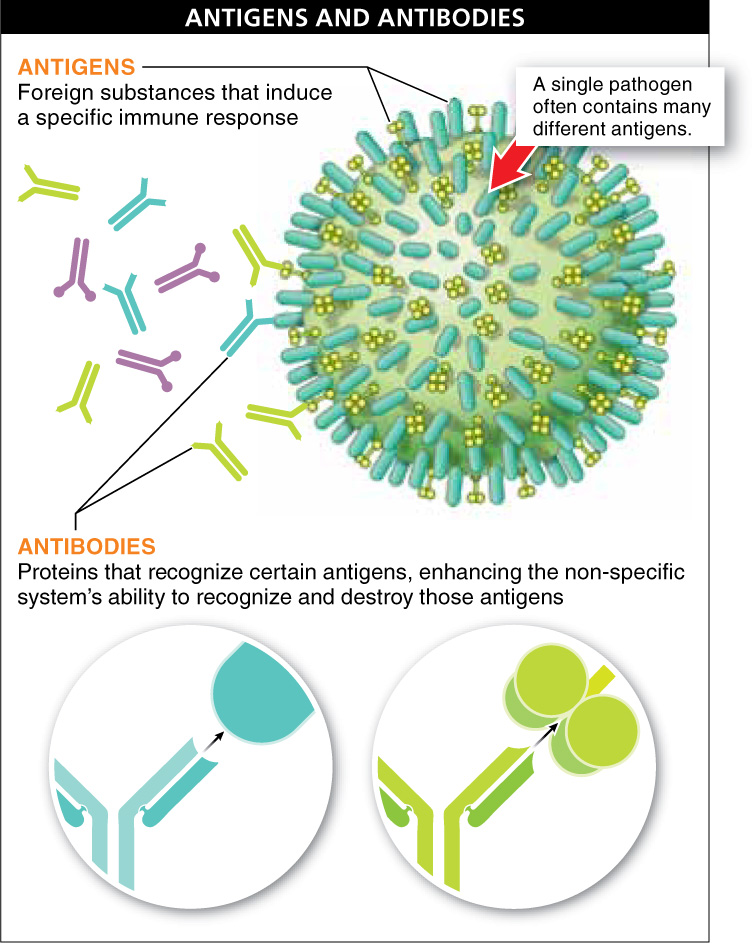

Let’s investigate how the immune system recognizes and responds to pathogens. An antigen is any molecule or fragment of a molecule that induces a specific immune response. A single pathogen often contains many different antigens (for example, the different glycoproteins, lipoproteins, and polysaccharides of a single bacterium can all be antigens). The body responds to antigens by making antibodies, circulating proteins that recognize specific antigens. (You can remember the difference between “antigen” and “antibody” by remembering that antigen is short for antibody generating.) Antibodies provide protection by enhancing the immune system’s ability to recognize and destroy pathogens such as bacteria and viruses and the body cells they infect (FIGURE 26-16). But keep in mind that antibodies don’t directly kill a pathogen. Instead, antibodies act as beacons that make pathogens conspicuous to patrolling phagocytes. Antibody levels peak within the first two weeks after encountering a pathogen or receiving a vaccine. We discuss the body’s ability to recognize and destroy antigens in the next section.

1058

Even though antibody production eventually diminishes, the specific immune system retains a memory of the disease. If the same antigen is encountered again, the body takes only 1–

The memory of the specific division of the immune system results in immunity, a state of long-

A vaccine is a weakened or harmless form of a specific pathogen that is administered to an individual to induce immunity, without subjecting the individual to the disease. Vaccines trick the body into thinking it has the full-

Today we have vaccines against numerous viruses (including polio, measles, rubella, mumps, and rotavirus) and bacteria (including tetanus, cholera, and meningitis). These vaccines are less available in the developing world, and thus, worldwide, many people die each year from what are now preventable illnesses.

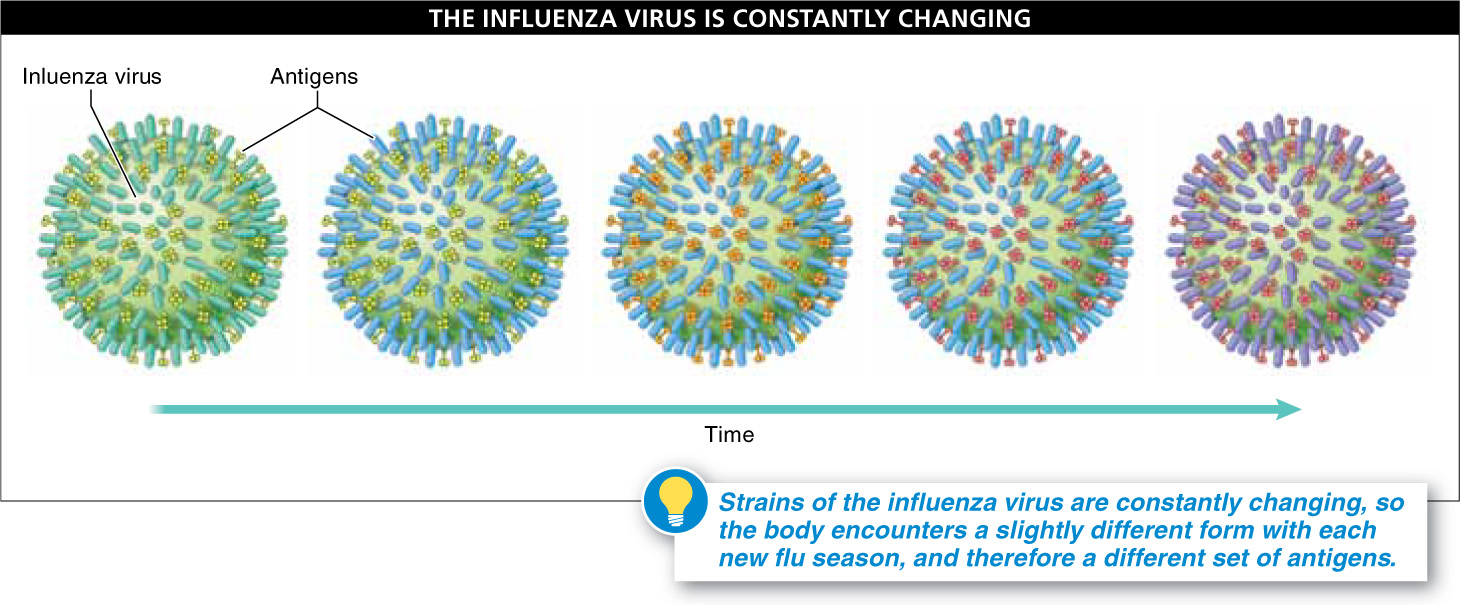

One of the most common infections fought off by the specific division of the immune system is influenza, an infectious disease caused by a virus. Each year there are many different versions, or strains, of the influenza virus, which are constantly changing. With each new flu season, the body encounters a slightly different form of an influenza virus and, therefore, a different set of antigens.

Because the influenza virus adapts to changing conditions and evolves, the best protection is to get a flu shot each year (FIGURE 26-18). And in the case of the flu vaccine, because any vaccine must contain an antigen, the vaccine is commonly made from an influenza virus (of the most common current strain or a mixture of strains) that has been inactivated by heat or from a live, weakened form of the virus that does not cause the flu. Although you can get the flu at any time of year, the flu season occurs in winter, so it makes sense to get vaccinated in autumn to give your body time to make antibodies that can protect you throughout the winter flu season. Every year a new flu vaccine is available in August or September.

1059

Yet, even with these preventive measures, a person may still get the flu. Although it is commonly thought that the flu shot itself can give someone the flu, this is simply not true. So, why do individuals sometimes get the flu after having the vaccination? There are several possible reasons. First, scientists developing the vaccine must make predictions, well before the flu season, about how the influenza virus will change in the upcoming season. Sometimes the vaccine “matches” the current virus, and sometimes it may be less than perfect. Second, different strains of the flu virus circulate at the same time, and the vaccine may not protect an individual from all strains. Lastly, a person might already be infected with the flu at the time of vaccination.

Why don’t people develop immunity to the common cold?

If the specific immune response can protect a person from illness during a future encounter with a specific pathogen, why is it that every winter you develop the runny nose, cough, and sore throat of the common cold? Why don’t you develop immunity to this most annoying and recurrent disease? Just like the influenza virus, the rhinovirus (“nose virus”), one of the viruses that cause the common cold, continually changes (FIGURE 26-19). Your immune system mounts a response to each version of the virus. Although rhinoviruses are a frequent cause of the common cold, they are not the only viruses that produce cold-

1060

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 26.5

Antigens are molecules or fragments of molecules on the surfaces of pathogens that can be identified by disease-

Briefly describe how vaccines work.

A vaccine introduces the antigen of a pathogen (via a weakened or harmless form of a specific pathogen), triggering the immune system to mount a specific immune response.